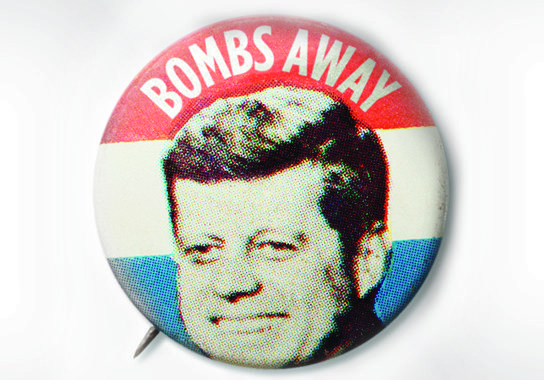

JFK, Warmonger

Fifty years is long enough to mold history into mythology, but in the case of John Fitzgerald Kennedy it only took a decade or so. Indeed, long before Lyndon Johnson slunk off into the sunset, driven out of office by antiwar protestors and a rebellion inside his own party, Americans were already nostalgic for the supposedly halcyon days of Camelot. Yet the graceless LBJ merely followed in the footsteps of his glamorous predecessor: the difference, especially in foreign policy, was only in the packaging.

While Kennedy didn’t live long enough to have much of an impact domestically, except in introducing glitz to an office that had previously disdained the appurtenances of Hollywood, in terms of America’s stance on the world stage—where a chief executive can do real damage quickly—his recklessness is nearly unmatched.

As a congressman, Kennedy was a Cold War hardliner, albeit with a “smart” twist. After a 1951 trip to Southeast Asia he said the methods of the colonial French relied too much on naked force: it was necessary, he insisted, to build a political resistance to Communism that relied on the nationalistic sentiment then arising everywhere in what we used to call the Third World. Yet he was no softie. While the Eisenhower administration refused to intervene actively in Southeast Asia, key Democrats in Congress were critical of Republican hesitancy and Kennedy was in the forefront of the push to up the Cold War ante: “Vietnam represents the cornerstone of the Free World in Southeast Asia,” he declared in 1956, “the keystone to the arch, the finger in the dike.”

As Eisenhower neared the end of his second term, Democrats portrayed him as an old man asleep at the wheel. This narrative was given added force by the sudden appearance of a heretofore unheralded “missile gap”—the mistaken belief that the Soviets were out-running and out-gunning us with their ability to strike the United States with intercontinental ballistic missiles.

This storyline was advanced by two signal events: the 1957 launching of Sputnik, the first artificial satellite to go into orbit around the earth, and the equally successful testing of a Soviet ICBM earlier that summer. That November, a secret report commissioned by Eisenhower warned that the Soviets were ahead of us in the nuclear-weapons field. The report was leaked, and the media went into a frenzy, with the Washington Post averring the U.S. was in dire danger of becoming “a second class power.” America, the Post declared, stood “exposed to an almost immediate threat from the missile-bristling Soviets.” The nation faced “cataclysmic peril in the face of rocketing Soviet military might.”

The “Gaither Report” speculated that there could be “hundreds” of hidden Soviet ICBMs ready to launch a nuclear first strike on the United States. As we now know, these “hidden” missiles were nonexistent—the Soviets had far fewer than the U.S. at the time. But the Cold War hype was coming fast and thick, and the Democrats pounced—none so hard as Kennedy, who was by then actively campaigning for president. “For the first time since the War of 1812,” he pontificated on the floor of the Senate, “foreign enemy forces potentially had become a direct and unmistakable threat to the continental United States, to our homes and to our people.”

To arms! The Commies are coming!

It was all balderdash. Barely a month after Kennedy was sworn in, this was acknowledged by Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara: there were “no signs of a Soviet crash effort to build ICBMs” he told reporters, and “there is no missile gap today.” Kennedy’s apologists have tried to spin this episode to show that Kennedy was misled. Yet Kennedy was briefed by the CIA in the midst of the 1960 presidential campaign, by which time the CIA’s projection of Soviet ICBMs had fallen from 500 to a mere 36. Kennedy chose to believe much higher Air Force estimates simply because they fit his preconceptions—and were politically useful.

When Eisenhower came into office, he swiftly concluded the Korean War and instituted his “New Look” defense policy, which cut the military budget by one third. He repudiated the Truman-era national-security doctrine embodied in “NSC-68,” a document prepared by Truman’s advisors that said the U.S. must be ready to fight two major land wars—and several “limited wars”—simultaneously. The U.S. was instead to rely on the threat of massive nuclear retaliation, a defensive posture derided at the time by Kennedy and his coterie as “isolationist.”

As president, Kennedy swiftly reversed Eisenhower’s course. McNamara rehabilitated NSC-68 and embarked on a massive buildup of conventional land, sea, and air forces in order to “prevent the steady erosion of the Free World through limited wars,” as Kennedy put it in a 1961 message to Congress. The promise of “limited” wars would soon be fulfilled by the two of the biggest disasters in the history of American foreign policy: the Bay of Pigs invasion and the Vietnam War.

While plans to overthrow Fidel Castro originated during the Eisenhower administration, the Bay of Pigs plot was conceived by the CIA shortly after Kennedy was sworn into office. During the last presidential debate before the election, Kennedy had attacked Eisenhower for his alleged complacency in the face of a “Soviet threat” a mere 90 miles from the Florida coastline. This left Kennedy’s rival, Vice President Richard Nixon, in the uncharacteristic position of defending a policy of caution. It was a typically disingenuous ploy on Kennedy’s part: the Democratic nominee had been briefed on the CIA’s regime-change plans shortly after the Democratic convention.

Kennedy, for his part, was enthusiastic about eliminating Castro. Once in office, he eagerly approved the CIA’s plan, and preparations began in earnest. The operation was a farce from the beginning. It depended on two projected events, neither of which occurred: the assassination of Castro and a widespread uprising against the Cuban government. This was the “they’ll shower us with rose petals” argument advanced 40 years before George W. Bush’s “liberation” of Iraq. It took less than two days for Cuban forces to squash the invaders.

Lurching from disaster to catastrophe, Kennedy, after barely a year in office, authorized an increase in aid to South Vietnam and sent 1,000 additional American “advisors.” While Lyndon Johnson usually gets the blame for escalating the Vietnam War, it was Kennedy who ordered the first substantial increase in direct U.S. involvement.

In his famous “pay any price, bear any burden” inaugural address, Kennedy put the Soviets on notice that his administration would prosecute the Cold War to the fullest, declaring that we “shall meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, in order to assure the survival and the success of liberty.” In Vietnam, this meant supporting the regime of Ngo Dinh Diem, whose dictatorship became increasingly repressive as Viet Cong forces gathered strength.

While the initial strategy, originated under Eisenhower, was predicated on supporting indigenous anti-Communist forces with aid and as many as 500 “advisors,” by 1963 U.S. troops in Vietnam numbered some 16,000. Long before the “COIN” theory promoted by Gen. David Petraeus in Iraq and Afghanistan, President Kennedy championed the doctrines of counterinsurgency to fight the Communists on their own terrain: the idea was to not only defeat the enemy militarily but also to materially improve the lives of the populace, whose hearts and minds must be won.

Thus was born the “Strategic Hamlets” program, which involved forcibly relocating millions of Vietnamese peasants from their villages and corralling them in government-run compounds. The idea was to isolate them from the pernicious influence of the Communists and provide them with healthcare, subsidized food, and other perks, while compensating them with cash for the loss of their dwellings.

The program was a horrific failure: torn from their homes, which were burned before their eyes, Vietnam’s peasants turned on the Diem regime with a vengeance. The compensation money that was supposed to go to the dislocated villagers instead filled the pockets of Diem’s corrupt officials, and the hamlets, which were soon infiltrated by the Viet Cong, turned out to be not so strategic after all. The ranks of the communists increased by 300 percent.

Kennedy, instead of holding his advisors—or himself—responsible for this abysmal failure, instead did what he always did: he blamed the other guy. After the Bay of Pigs ended in what the historian Trumbull Higgins called “the perfect failure,” Kennedy put the onus on the CIA—although he had approved the original plan, which called for U.S. air support for the Cuban exile force, only to withdraw his promise on the eve of the invasion. Similarly when it came to the unraveling of South Vietnam, he blamed Diem.

By 1963 Diem had opened back-channel talks with the North Vietnamese and sought to end the war with a negotiated settlement, but Kennedy was having none of it. The president soon concluded that the increasingly unpopular Diem was the cause of America’s failure in the region and—disdaining the advice of the Pentagon—agreed to a State Department plan to overthrow him.

A cash payment of $40,000 was made to a cabal of South Vietnamese generals, and on November 2, 1963, the president of the Republic of Vietnam was murdered, along with several members of his family. The coup leaders were invited to the American Embassy and congratulated by Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge.

Chaos ensued, and the Vietcong was on the march. In response, U.S. soldiers increasingly took the place of ARVN troops on the battlefields of Vietnam. The Americanization of the war had begun. According to Robert Kennedy—and contrary to Oliver Stone’s overactive imagination—JFK never gave the slightest consideration to pulling out.

The mythology of Kennedy’s “dazzling” leadership, as hagiographer Arthur Schlesinger Jr. once described it, reaches no greater height of mendacity than in official accounts of the Cuban missile crisis. In the hagiographies, the heroic Kennedy stood “eyeball to eyeball” with the Soviets, who—for no reason at all—suddenly decided to put missiles in Cuba. Because Kennedy refused to back down, so the story goes, America was saved from near certain nuclear annihilation.

This is truth inverted. To begin with, Kennedy provoked the crisis and had been forewarned of the possible consequences of his actions long in advance. In 1961, the president ordered the deployment of intermediate range Jupiter missiles—considered “first strike” weapons—in Italy and Turkey, within range of Moscow, Leningrad, and other major Soviet cities. In tandem with his massive rearmament program and the continuing efforts to destabilize Cuba, this was a considerable provocation. As Benjamin Schwarz relates in The Atlantic, Sen. Albert Gore Sr. brought the issue up in a closed hearing over a year and a half before the crisis broke, wondering aloud “what our attitude would be” if, as Schwarz writes, “the Soviets deployed nuclear-armed missiles to Cuba.”

Kennedy taped many of his meetings with advisors, and those relevant to the Cuban missile crisis were declassified in 1997. They show that Kennedy and his men knew the real score. As Kennedy sarcastically remarked during one of these powwows: “Why does [Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev] put these in there, though? … It’s just as if we suddenly began to put a major number of MRBMs [medium-range ballistic missiles] in Turkey. Now that’d be goddamned dangerous, I would think.”

National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy, not known for his sense of humor, helpfully pointed out: “Well we did it, Mr. President.”

Kennedy and his coterie realized that the deployment of Soviet missiles in Cuba didn’t affect the nuclear balance of power one way or the other, although the president said the opposite in public. In a nationally televised address on the eve of the crisis, the president portrayed the Soviet move as “an explicit threat to the peace and security of all the Americas.” In council with his advisors, however, he blithely dismissed the threat: “It doesn’t make any difference if you get blown up by an ICBM flying from the Soviet Union or one that was 90 miles away. Geography doesn’t mean that much.” In conference with the president, McNamara stated, “I’ll be quite frank. I don’t think there is a military problem here … This is a domestic, political problem.”

The “crisis” was symbolic rather than actual. There was no more danger of a Soviet first strike than had existed previously. What Kennedy feared was a first strike by the Republicans, who were sure to launch an attack on the administration and accuse it of being “soft on Communism.”

Thus for domestic political reasons, rather than to address a real military threat, Kennedy risked an all-out nuclear war with the Soviet Union. His blockade of Cuba and the public ultimatum delivered to the Soviets—withdraw or risk war—brought the world to the brink of the unthinkable. Yet as far as anyone knew at the time, it worked: the Soviets withdrew their missiles, and the world breathed a sigh of relief.

Only years later, as new materials were declassified, was the secret deal between Kennedy and Khrushchev revealed: Kennedy agreed to withdraw our missiles from Turkey and promised not to invade Cuba. Another aspect of the Kennedy family mythology was exposed by these releases: brother Robert, far from being the reasonable peacemaker type he and his family’s chroniclers depicted in their memoirs and histories, was the most Strangelove-like of the president’s advisors, calling for an outright invasion of Cuba in response to the ginned up crisis.

Perhaps in this matter he was taking his cues from his brother, who during the Berlin standoff had actually called on his generals to come up with a plan for a nuclear first strike against the Soviets.

Stripped of glitz, glamour, and partisan myopia, the Kennedy presidency was the logical prelude to the years of domestic turmoil and foreign folly that followed his assassination. President Johnson was left to carry the flag of Cold War liberalism into what became the “Vietnam era,” but that tattered banner was lowered when LBJ fled the field, McGovernites took over his party, and the hawkish senator Scoop Jackson’s little band of neocons-to-be made off to the GOP. This is the real Kennedy legacy: not the mythical “Camelot” out of some screenwriter’s imagination, but the all-too-real—and absurdly hyperbolic—idea that America would and could “pay any price” and “bear any burden” in the service of a militant interventionism.

Justin Raimondo is editorial director of Antiwar.com.