Is the Religious Right to Blame for Christianity’s Decline?

No one will be surprised to learn that religious beliefs, affiliations, and activities are important predictors of political attitudes and actions. This is one of the more well-studied subjects in the field of political behavior. Most of the literature examining this relationship, however, assumed a causal arrow that points in only one direction: religion influences politics. The stack of books and papers considering whether trends in politics influence trends in religion is much shorter. This is starting to change, and the results of this research increasingly suggests that the Religious Right played at least some role in America’s declining religiosity.

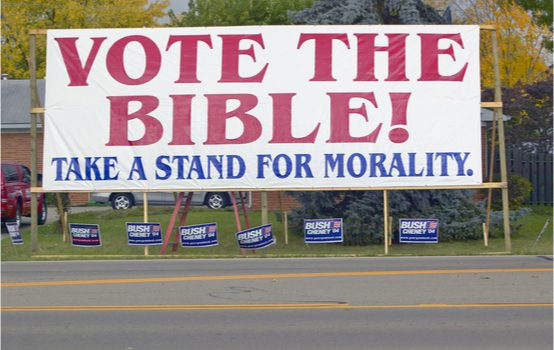

As the number of Americans that identified with no religion began increasing in the 1990s, scholars and journalists began to look for explanations. Especially among pundits, these explanations typically favored their own cultural, theological, and political prejudices. To lay my own cards on the table, I am persuaded that fertility rates are one of the best predictors of a Christian denomination’s long-term health. That said, it would be remarkable if politics did not have any effect on religious trends, given the degree to which American religion has been so politicized since the rise of the Religious Right in the late 1970s.

For a time, it was frequently argued that Christianity was on the decline because Americans were fleeing liberal mainline denominations. This was not implausible. Looking at trends in American religion in the late 20th century, it was easy to discern that, on average, the mainline Protestant denominations were declining rapidly. And until recently, the more theologically-conservative evangelical denominations continued to experience growth, or at least hold steady.

This led the Religious Right to crow that their more conservative theological and political stances were yielding dividends in the pews. They argued that liberal churches had abandoned biblical teachings in favor of more fashionable political causes, but these efforts to “get with the times” failed to bring in new members. Even worse, it caused them to lose existing members to secularism, or nudged them toward more conservative expressions of Christianity, especially evangelical Protestantism.

One does not often hear this argument anymore.

As plausible as this theory may have appeared a decade ago, recent trends in American religious life suggest it is incomplete, if not entirely wrong. The more traditionalist evangelical denominations have now begun a nosedive of their own. And to make matters worse for those denominations that once formed the backbone of the Religious Right, the growth we do see among evangelicals comes largely from Pentecostal denominations, which, on average, are not especially (politically) conservative.

The decline of many evangelical denominations, including the Southern Baptist Convention, seems to give new credibility to the argument that the Religious Right was, overall, a detriment to Christianity in the United States. Such a claim, however, is difficult to demonstrate empirically.

In the most influential article on this subject, Michael Hout and Claude Fischer made this case in 2002. They argued that, as the Religious Right became increasingly visible and militant, it became associated with Christianity itself. And if being a Christian meant being associated with the likes of Jerry Falwell, many people—especially political moderates and liberals—decided to simply stop identifying as Christians altogether. This was especially true of people whose religious attachments were already weak.

The results of Hout and Fischer’s analysis were congruent with their hypothesis, though given the limitations of their methods, one could reasonably claim that they failed to decisively prove their case. But in the subsequent decade and a half, additional research has further strengthened their argument. American Grace, by Robert Putnam and David Campbell, for example, argued that declining levels of religious affiliation can be partly attributed to the Christian Right. A subsequent study by Hout and Fischer provided similar results.

Our understanding of this subject took a significant step forward recently thanks to a new article by Paul Djupe, Jacob Neiheisel, and Anand Sokhey. In “Reconsidering the Role of Politics in Leaving Religion,” the authors provide new evidence that disagreement with the Religious Right was a catalyst for some people’s withdrawal from Christianity. These scholars approached the subject somewhat differently, focusing on affiliation with a particular congregation, rather than personal identification with a particular religion.

The focus on congregational affiliation is important, as it arguably has greater social consequences than religious identification. One can wonder, after all, how much it really matters if a person who engaged in no religious activities to begin with stops telling pollsters that he is a Christian, but otherwise changes nothing.

The studies conducted by Hout and Fischer indicated that the Religious Right inadvertently drove down religious identification among liberals and moderates. Using three separate data sets, however, Djupe, Neiheisel, and Sokhey showed that the Religious Right may have also driven some evangelical Republicans from their congregations. Specifically, Republican evangelicals that disagreed with the Religious Right were more likely to leave their churches.

It is important not to overstate these effects; as the authors noted, congregational disaffiliation due to disagreement with the Religious Right was most common among people who were weakly attached to their churches to begin with. The declining levels of every measure of religiosity in America can be attributed to multiple causes, and no one is arguing that the Religious Right is the sole (or even the primary) culprit.

Given the Religious Right’s record of success on other fronts, however, the finding that it expedited the decline of Christian identification and affiliation is a damning indictment of the movement.

In the realm of politics, the Religious Right was an abysmal failure. It was an effective fundraising tool for Republican politicians, but its lasting victories in terms of social policies are difficult to name. Stopping the Equal Rights Amendment in the late 1970s was perhaps the movement’s sole permanent achievement. And that victory occurred before most of the major institutions of the Christian Right were even established. On abortion, gay marriage, prayer in school, and other social issues, conservative victories were typically fleeting.

Despite the hundreds of thousands of Americans that formally joined institutions associated with the Religious Right, and the untold millions spent on lobbying and activism, the movement’s long-term impact on public policy seems negligible. It is hardly surprising that the Religious Right is no longer even perceived as a relevant force in U.S. politics. Far from a kingmaker in the political arena, the Christian Right is now mostly ignored.

Many political movements flop, and those sympathetic to the Religious Right may want to at least give the movement credit for fighting for its beliefs, however ineffectual it was. Lots of political non-profits have an abysmal return on investment. But if the research on religious decline and the Religious Right is correct, and the movement played even a small role in expediting the decline of Americans’ religiosity, it deserves to be judged as one of the most dramatic failures in American political history.

George Hawley (@georgehawleyUA) is an assistant professor of political science at the University of Alabama. His books include Right-Wing Critics of American Conservatism, White Voters in 21st Century America, and Making Sense of the Alt-Right (forthcoming).

Comments