Indian Blood

We can no longer indulge the fantasies and false histories of those who hate this country and its people.

Like Elizabeth Warren, my family has legends.

It was always believed that my great grandmother was part Native American—I think the story was Sioux, maybe for no better reason than that she came from Sioux City, Iowa. A little research shows the legend was nothing more than that. Her name was Grout, and it traced in this country back to John Grout, my tenth great grandfather, who arrived in Massachusetts from England sometime before 1640 and died there in 1697. Every line of her ancestry—with names like Garrison, Cook, Atwood, and Crane—traces back to before the Revolution, and more than one ends at the Mayflower.

If you tested her DNA, I suppose she would have been 100% English. Her forefathers, when they defended their rights against the abuses of Parliament after England had fallen to the Dutch and other evils, still thought of themselves as Englishmen. But she never saw England. She was born in Sioux City in 1918 and died in Boston, where her family had been for almost four centuries. If she was not a native American, who is?

I might as well ask the same for myself. The latest of my American ancestors, Timothy McMahon, came to Boston from Limerick in 1887, five years before the immigration center opened at Ellis Island. (On second thought, that’s not actually true. My grandmother’s father came from Quebec as a young boy. His sixth great grandmother, Hélène Desportes, was the first white person born in Canada; her godfather was Samuel de Champlain.) Do I not have a claim to this country at least as strong as the descendants of those scattered pagan tribes whose villages dotted it here and there before my ancestors brought Christian civilization across the ocean?

It is customary to be diplomatic about these things, but the time for politesse is quickly passing. Two days ago, the patriotic and well-adjusted among us sat down with our families and enjoyed Thanksgiving dinner. The anti-social discontents of the racial left spent the holiday wallowing in resentment, wailing to anyone who would listen that the traditional celebration of the harvest festival “obscures the harsh truth, one steeped in colonialism, violence, and misrepresentation.”

These particular words are those of Sean Sherman, an Oglala Lakota who wrote in the Nation this week on the need to “decolonize Thanksgiving.” He claims to be interested in the full truth of our history, but nearly omits mention of Plymouth altogether. He makes a passing reference to a celebration of the safe return of soldiers during the Pequot War in 1637, and dismisses “the image of Thanksgiving [as] one of supposed unity: the gathering of ‘Pilgrims and Indians’ in a harmonious feast.” Sherman seems not to understand even the basic facts of history, but expecting a Lakota chef to care about a meal shared by Wampanoag and Englishmen is a bit like asking a member of the Hungarian parliament to weigh in on relations between Laos and Vietnam. What does it have to do with him?

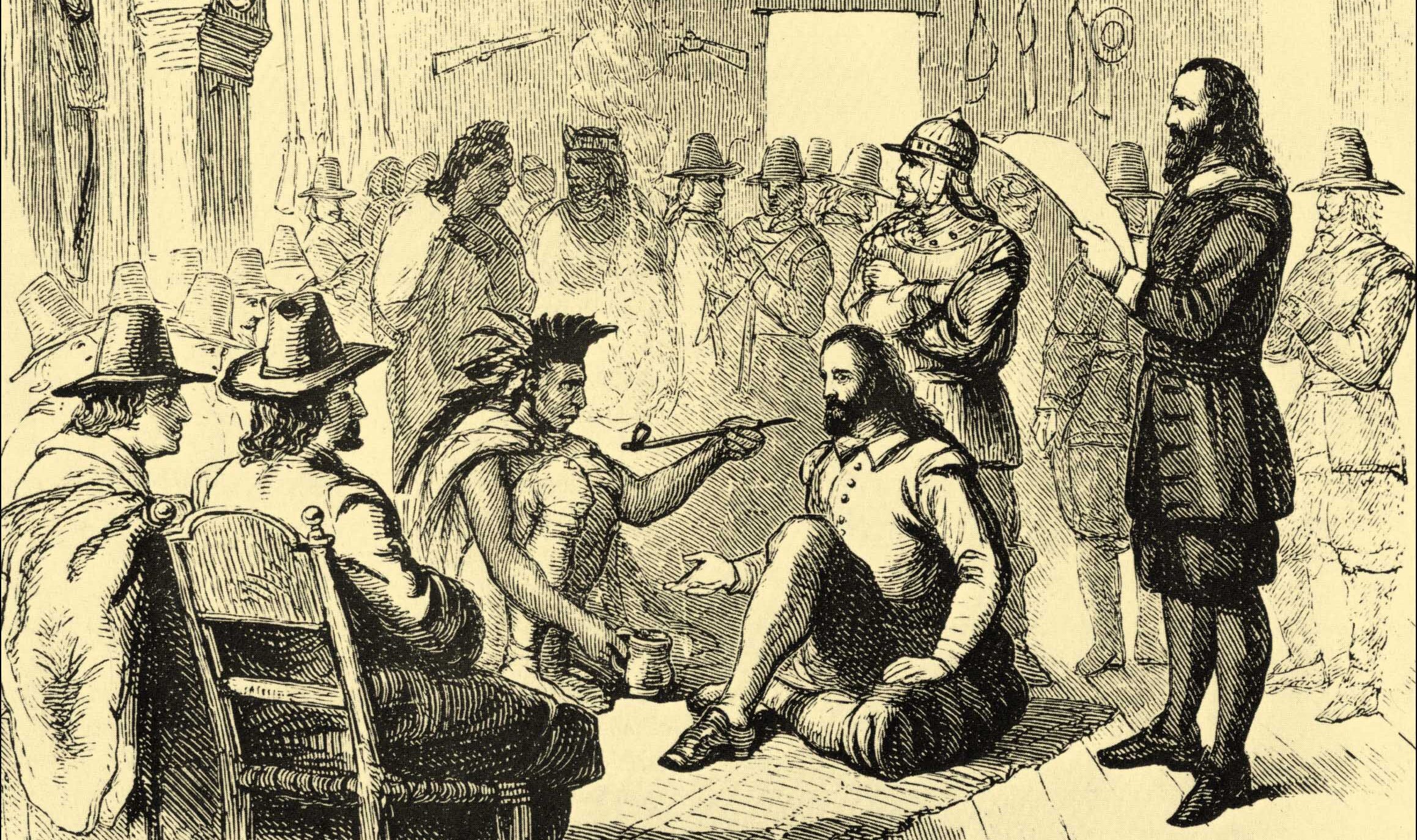

In the real world, the storybook version of Thanksgiving does just fine. The place that became Plymouth—which Champlain had called Port St. Louis—was once the village of the Patuxet band of Wampanoag, but they had been wiped out by plague, leaving sheltered and fertile land open for the settlement of a new people. The Wampanoag were friends and allies of the Pilgrims; they came to the feast to investigate the celebratory gunfire, and wound up staying for three days. They brought corn to bake bread and killed five deer as gifts to their new neighbors. It was a spontaneous and genuine moment of harmony almost without parallels elsewhere in history. The people of Plymouth may well not have survived without the aid of Squanto, Massasoit, others who helped them to farm and broker peace. There are indeed debts here that endure through generations.

But that is not the whole story. When the first Europeans planted their settlements in the New World, they stumbled into a complex web of alliances and enmities, dropped uneasily amid the ever-shifting boundaries of bands and federations. Tribal conflict was petty and vicious—war of a smaller scale but a far harsher character than that known to early modern Europe. The Pilgrims’ first encounter with the indigenous peoples was one of arrows, not words. In spite of the miracle we rightly celebrate at Thanksgiving, those realities endured.

The Pequot War cited by Sherman is a prime example. It is true that civilians, probably many, were among those killed in the English attack on the Pequot fort at Mystic; this is a sin beyond our purview to redress. But the simplistic narrative of aggressor and victim, settler and indigenous, does not do any justice. The Mystic raid came near the tail end of a three-year war which stemmed from Pequot attempts to expand into the territory of other tribes and consolidate control over the fur trade. The hostilities escalated into full-scale war after the murder of the merchant John Oldham and his crew, the capture of his young nephews, and the theft of his ship’s cargo. Multiple native tribes were allied with the English against the Pequot (whose own allies included the rival Dutch settlers). The Mystic raid was of a piece with the brutality and rivalry that defined early New England, and it can hardly be separated from the human reality of civilization breaking into an untamed continent.

The Pequot War was relatively short, and its casualties numbered in the hundreds. A far bloodier engagement came four decades later, when the Wampanoag chief Metacomet forgot the friendship between his father, Massasoit, and the Englishmen at Plymouth. That friendship was so strong that Metacomet was given an English name, too, by which today almost exclusively King Philip is remembered. The conflict was brief but exceptionally bloody, with atrocities committed by both sides, thousands dead on each, and a dozen English towns wiped off the map entirely. Among the chief targets was Sudbury, a little town northwest of Boston. On April 21, 1676, Metacomet’s forces mounted an ambush, burning most of the village, killing indiscriminately, and trapping civilian survivors in the fortified garrison.

John Grout was about 60 then—older than many men lived in those harsh early years. As a younger man he had fought in the Pequot War, so the command of Sudbury’s modest militia fell to him. It is speculated that he was the grandson of Sir Richard Groutte, who was knighted by Queen Elizabeth in 1587; we know he was an expert in the use of the halberd, an old medieval weapon that made him a bit of a man out of time. With just a few men, this latter-day Horatius held off a force of at least 500 warriors until reinforcements could arrive from the nearby towns. After a hard-won victory, John was called to Boston and honored with a captaincy—the New World equivalent of the knighthood his grandfather had received from the queen. The Sudbury fight was the last major engagement, and Metacomet’s aggression was soon quelled by decisive force of arms.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

The bloodshed did not stop there. For another two centuries the peoples of America, red and white alike, warred with each other over land, hatred, and other disputes. The story of the frontier is in large part a story of rape and kidnap, butchery and scalping. The Indian wars are indeed a dark chapter of our past, but not as a simple tale of indigenous heroes and settler villains. If these people really want to probe into the history of this continent and its nations, let them.

There’s the rub. The blood-and-soil sensibilities of the new indigenous activism are unsettling, but they are also poorly founded. The entire concept of a “Native American” identity is derived backwards from the reality of the American nation from 1620 onward. What is an Apache to a Wampanoag? In pre-contact America, there were coastal fishermen and Great Plains nomads and desert people and roving warriors. There is much to be admired among these disparate peoples, but there is far less of the makings of civilization than is fashionable to admit. (There were also pagan empires that sacrificed children to demons by the hundreds just as the great cathedrals rose in cities across Europe.)

Let that be part of the story. Let those who insist on a fuller and more honest treatment of our past live up to their own wish. Give Squanto and Massasoit and all friends of our forefathers the honor and the thanks that they deserve. But give the same to the Pilgrim Fathers, and to John Grout, and to the hardy pioneers who endured the terrors of the frontier in hopes that they might carve a great nation at the edge of a savage world.