Incense for the Emperor

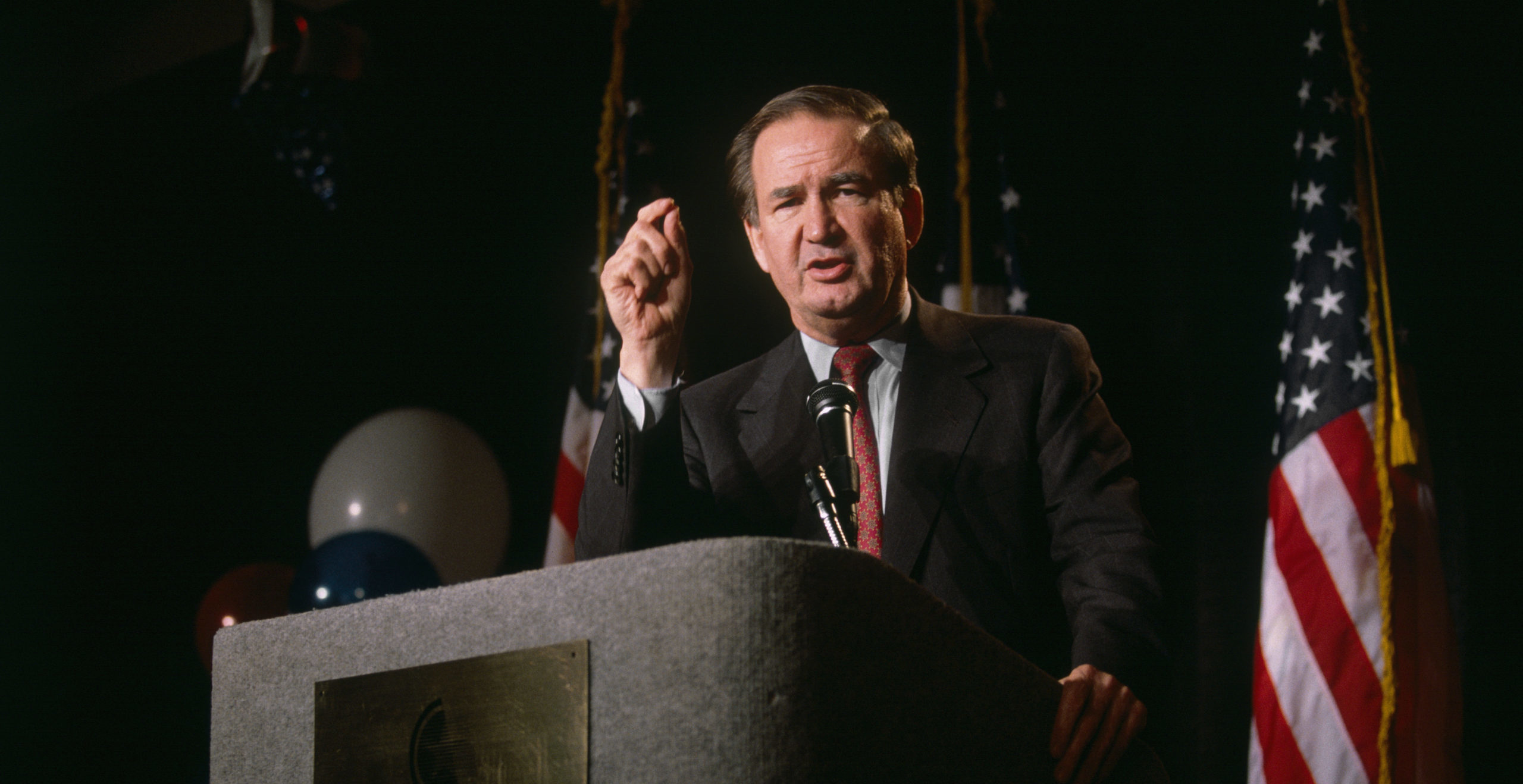

Revisiting Pat Buchanan’s culture war speech after thirty years.

Thirty years ago this past Thursday, Patrick J. Buchanan gave a primetime address at the Republican National Convention in Houston, Texas. Buchanan had lost every primary to President George H.W. Bush, though he did garner just short of three-million votes against the incumbent’s nine. Yet he came to Houston with no confusion about who his enemies were: the Democrats who had just held their own convention in New York City the month before, and not the Bush-backing Republicans who made up his audience.

Buchanan described that earlier meeting as a “giant masquerade ball up at Madison Square Garden—where 20,000 liberals and radicals came dressed up as moderates and centrists—in the greatest single exhibition of cross-dressing in American political history.”

In those last days of the American Century, not even Pat Buchanan could have known how much worse it was going to get. We don’t have hard numbers ready at hand, but I’d be willing to bet there is more cross-dressing per capita in American public libraries today than you might have had the misfortune of finding at the Democrats’ 1992 convention.

That was the point all along. Buchanan’s ‘92 address has gone down in history as the “culture war speech,” after one pivotal line: “There is a religious war going on in this country. It is a cultural war, as critical to the kind of nation we shall be as was the Cold War itself, for this war is for the soul of America.”

He warned his comrades in that fight of “the agenda that Clinton & Clinton would impose on America—abortion on demand, a litmus test for the Supreme Court, homosexual rights, discrimination against religious schools, women in combat units.” On all of these and more, Buchanan’s words have proven prophetic.

Abortion especially was then at a pivotal point. Buchanan observed that Pennsylvania’s Governor Bob Casey—a member of the already vanishing species of pro-life Democrat—had been denied the opportunity to speak on the sanctity of life at that year’s DNC. By virtue of his office, Casey had just lent his name to the now-infamous Supreme Court case in which Pennsylvania’s pro-life law was gutted and Roe v. Wade was reaffirmed.

It seemed in the wake of Planned Parenthood v. Casey that the genocide of the unborn would march on unrelentingly until the end of time—or, at least, until the end of America. But Buchanan has lived to see Roe v. Wade completely overturned. Dobbs, though, marks not an end to the culture war but merely the start of a new campaign. The rhetoric of spiritual combat that Buchanan employed a generation ago is only more relevant now that Roe’s demise has pushed it back into the open.

On homosexuality, too, Buchanan’s words were prescient. After Mario Cuomo accused him of Nazi rhetoric on primetime CBS, Buchanan expanded on the speech’s controversial lines in a September 14 column. He wrote:

Americans are a tolerant people. But a majority believes that the sexual practices of gays, whether a result of nature or nurture, are both morally wrong and medically ruinous. Many consider this “reactionary” or “homophobic.” But our beliefs are rooted in the Old and New Testament, in natural law and tradition, even in the writing of that paragon of the Enlightenment, Thomas Jefferson (who felt homosexuality should be punished as severely as rape).

This is not just defensible but obviously right. All Buchanan asked for then was the privilege to believe in America what the vast majority of men in the West have believed since Truth overcame the last great pagan empire. There was no sting of hatred there, no call to violence or persecution. He simply objected to “the non-negotiable demand that this ‘lifestyle’ be sanctioned by law, that gays be granted equal rights to marry, adopt and serve as troop leaders in the Boy Scouts.”

“We can’t support this,” Buchanan wrote. “To force it upon us is like forcing Christians to burn incense to the emperor.” And so it is. Yet the right—enough of it, at least, to tilt the scales—refused to listen. Every little concession, every refusal to fight, every time movement conservatives scoffed at the radicals or distanced themselves from us, has led America to this point. Queer pornography is commonplace in public-school libraries, drag queens are a fixture of children's entertainment, juvenile sex changes are rapidly being normalized, and the women of the third world serve as rented wombs for Americans' designer babies. And if you dare even to suggest that people of certain proclivities should not serve as troop leaders in the (no longer extant) Boy Scouts, that the law should not encourage them to marry and adopt, you are cast into the outer darkness not just by the radical left but by the heirs to the Bush Republicans.

Because this is, as Buchanan recognized thirty years ago, an all-encompassing religious war. It was not in 1992, nor is it now, about simple disagreements over policy or tone, over where to set limits or how far to compromise. It is and has always been a life-or-death struggle between two irreconcilable understandings of the American national character and the moral order of the universe.

We've come close to that just once before. Reflecting on the first Civil War, and the crusade to rewrite its history, Buchanan encouraged his readers to drive to the famous battlefield at Gettysburg:

Look across that mile-long field and visualize 15,000 men and boys forming up at the tree line. See them walking across into the fire of cannon and gun, knowing they would never get back, never see home again. Nine of ten never even owned a slave. They were fighting for the things for which men have always fought: family, faith, friends, and country. For the ashes of their fathers and the temples of their Gods.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

I am a son of Massachusetts in spirit as much as in fact, and I have no real sympathy for the cause of the Confederates. (Buchanan, descended from Mississippi veterans of the war, understandably might feel otherwise.) Yet I can muster for its partisans even admiration, and can only hope that, put to the test, I too could face the fire of cannon and gun for family, faith, friends, and country.

The same cannot be said of the shock troops of the culture war. I cannot imagine—nor would I want to—my own great-grandson, another century down the line, writing a paragraph like the one quoted above about the terrorists who firebomb churches and women's centers in support of the right to slaughter the unborn; about the mad scientists who mutilate children and manufacture babies in the name of liberation; about the wild mobs that burned our cities and looted our stores and murdered for sport in the summer of 2020.

But this, too, was predictable by 1992. In that September column Buchanan quoted Muggeridge quoting Dostoevsky’s Peter Vekovinsky in The Devils: “‘A generation or two of debauchery followed by a little sweet bloodletting and the turmoil will begin.’ So indeed it has.”

Comments