In Praise of Middlemarch

Good morning. I hope you each had a joyous holiday, full of good food, great conversation, and long afternoon naps. Here in southeastern Virginia, Christmas and New Year’s Eve were smaller affairs than usual. Our two elder daughters couldn’t be with us (one is in Victoria, BC and one is in Germany), and we decided not to hold our annual neighborhood New Year’s bash. Still, we connected with the girls and friends in other ways. Life goes on.

I didn’t finish any of the books I started, but I knocked out 4 puzzles (with more than a little help from wife and daughter), and I was able to fit in a couple of longish bike rides and make some solid progress on an anthology I’m working on (more on that later this year). So it was a productive break, too.

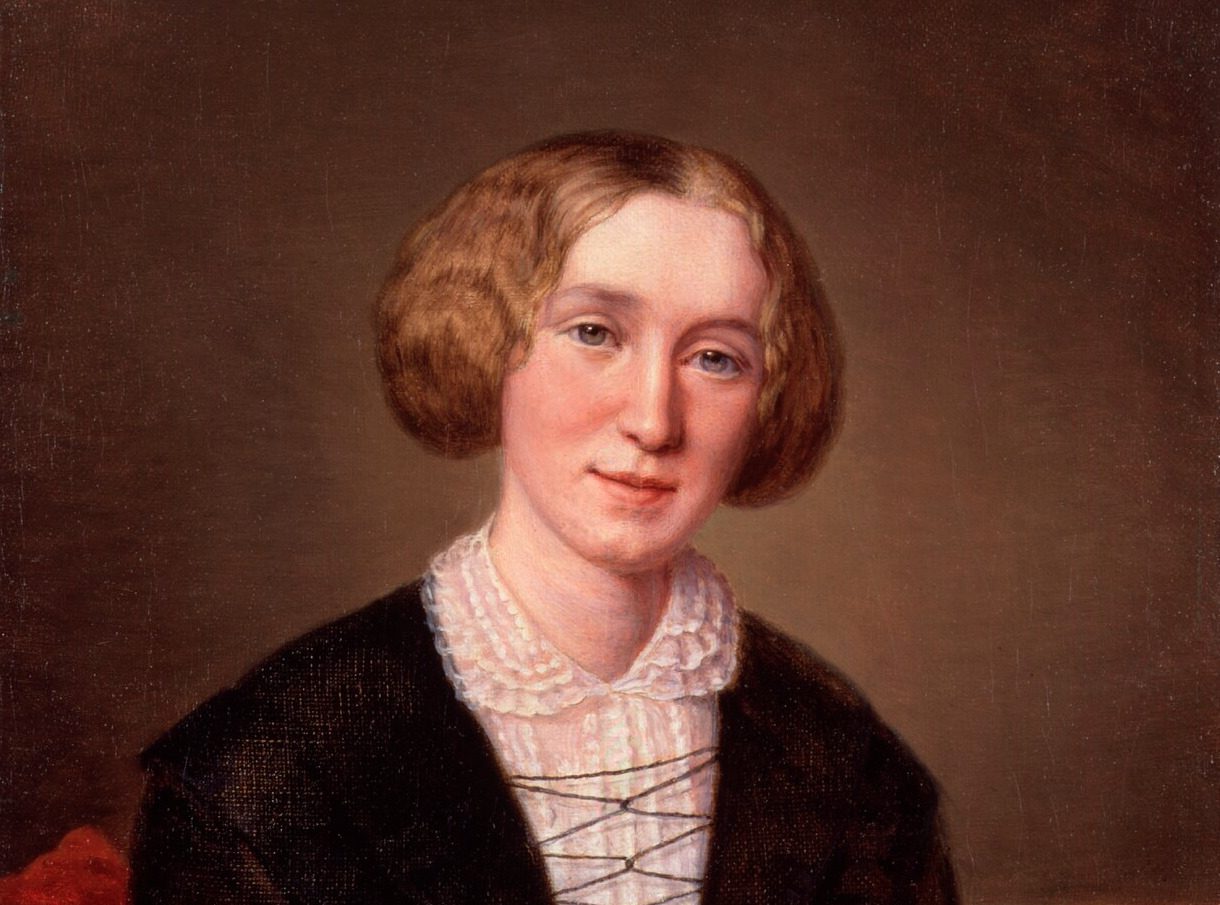

But now it’s over, so let’s get to it. In The New Criterion, Myron Magnet offers an appreciation of Middlemarch: “‘Know thyself’ is easy to say; but how, exactly, are we mortals supposed to obey the Delphic command? Surely not through the human ‘sciences.’ Psychology, sociology, and anthropology all seem misapplications of a method of inquiry too abstract to explain messy human reality, depersonalizing what is quintessentially personal. If you want to make sense of human actuality, to ponder what makes our lives meaningful and why we do what we do, think what we think, and hope what we hope, the best guide I know is literature. A recent rereading of Middlemarch brought that thought home forcefully, and the decades since my last reading have taught me also to appreciate why so many authors consider this the greatest of all English novels, one of the few, Virginia Woolf thought, written for grown-ups.”

John Wilson reviews Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence: “If bad sentences make your brain hurt; if good sentences absorb your attention; if, like Kenner, you enjoy to a near-pathological degree ‘constructing English sentences’ of your own and finding in ‘other people’s books . . . the endless ways their structures can be combined,’ I have just the thing for you. Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence is a tour de force of exposition, witty, learned but jargon-free, the work of a writer who is agreeably idiosyncratic. It consists of Dillon’s close readings and reflections on 27 sentences, in chronological sequence, from Shakespeare to Anne Boyer. An introductory chapter traces the origins and ground rules of the project; each short chapter thereafter begins with the sentence in question, exposition of which will also entail a look at other sentences.”

Randy Boyagoda takes stock of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan series: “The books were so readable that I couldn’t wait for Anna to finish reading the hard copies we owned. The story of two little girls growing up in Naples in the 1950s may not sound like the most engrossing reading, but it is, because of how Ferrante uses intense storytelling to illuminate the interior lives of her characters.”

One of the first artists to paint everyday things was the Master of Flémalle. Who was he? “There are many marvelous things to be seen in the Musée des Beaux-Arts at Dijon. But when I paid a visit a couple of years ago (in those days you could just step on a train and do such things), it was a little picture of the Nativity that particularly caught my eye. Its date, artist and original owner are all uncertain, but its beauty and originality were clear at a glance. Here, for almost the first time in European art, the appearance of ordinary things and people were the subject of close, rapt observation.”

Hillel Halkin revisits Steve Kogan’s Winter Vigil: “The thing about social change, especially when it’s technologically driven, is that the good always comes with the bad. It’s a package deal. Modern medicine can cure an array of once untreatable diseases, but where are the days, remembered by Kogan and me, when family doctors routinely made house calls and came when you needed them? The automobile shrank distances, relieved the isolation of millions, clogged roads and streets, exfoliated cities, poisoned their air. Television educated and entertained generations of viewers while reducing large numbers of them to stupefaction. Air travel, computers, smartphones, social media—you can say the same for them all. Winter Vigil doesn’t say it by arguing. Mostly, Kogan makes the case for the times he grew up in by describing their rich texture and leaving us to compare them with being young today.”

Sam Weller and Dana Gioia talk about Ray Bradbury: “Regional identity matters more in American literature than many critics assume. We have a very mobile society, so today many writers are almost placeless. But Bradbury is a perfect example of a writer for whom regional identity was very important.”

The time Theodore Dreiser slapped Sinclair Lewis in the face . . . twice: “At the banquet Dorothy and Sinclair avoided Theodore, but when America’s new Nobel laureate was asked to say a few words, Lewis stood up and announced, ‘I feel disinclined to say anything in the presence of the son of a bitch who stole 3,000 words from my wife’s book.’ After dinner Dreiser confronted the inebriated Lewis and dared him to repeat his accusation. When Lewis obliged, Dreiser slapped his face. While a bystander held Lewis’s limp arms, Dreiser again challenged him to repeat his charge. Lewis did, and was slapped again. At that point Dreiser was asked to leave, and he did so as fast as he could.”

Photos: Alaska

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.