Hurricane Laura Savage Storm Surge

I hope this blog’s readers in the area from Galveston over to southwestern Louisiana are not reading this, because they should be in the process of getting out of the way of Hurricane Laura. I checked on this blog’s regular commenter Leslie Fain, who lives in southwest Louisiana. She and her mom and her youngest child have evacuated north, but her husband and older sons are still there, taking care of all their animals. Please pray for them, and for all the people who will bear the brunt of the storm.

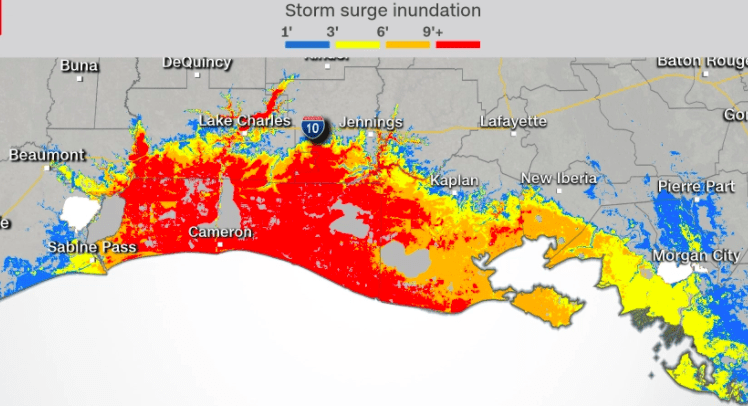

Unsurvivable storm surge with large and destructive waves will cause catastrophic damage from Sea Rim State Park, Texas, to Intracoastal City, Louisiana, including Calcasieu and Sabine Lakes. This surge could penetrate up to 30 miles inland from the immediate coastline. #Laura pic.twitter.com/bV4jzT3Chd

— National Hurricane Center (@NHC_Atlantic) August 26, 2020

I live in Baton Rouge, which means the main thing we will have to worry about is the possibility of tornadoes spun off of this thing, and spot flash flooding. If we can avoid a twister, we’ll be okay.

Laura is probably not the storm that’s going to do this, but still, it’s worth reading about the future hurricane that could turn Houston into “America’s Chernobyl.” Peter Holley writes in Texas Monthly:

The storm emerges over the eastern Atlantic in late August, first as a slow-moving tropical system that remains largely unnoticed in faraway Texas. It gains power as it drifts westward into warmer Caribbean waters, lashing island coastlines and leaving a trail of destruction in its wake. By the time the storm enters the Gulf of Mexico and churns toward the southeast corner of Texas, it has transformed into a category 4 hurricane with 130-mile-per-hour winds that fan out for 200 miles in every direction.

Unlike 2017’s Hurricane Harvey, which made landfall just north of Corpus Christi, the swirling behemoth slams into land some two hundred miles up the coastline near Galveston Island. As the hurricane moves inland, it functions like a giant wall of wind, pushing water north from Galveston Bay—one of the largest estuaries in the United States—into the smaller bays, rivers, and bayous that comprise the Houston Ship Channel, home of the largest petrochemical energy complex in the United States.

This is a hypothetical that Terence O’Rourke, an environmental attorney and hydrology expert with the Harris County Attorney’s Office, has been warning public officials about for the last decade. He says what comes next in the disaster scenario would become “America’s version of Chernobyl”—the Soviet nuclear power plant that melted down in 1986, killing 4,000 people over time and forcing the evacuation of nearly 50,000. The storm O’Rourke predicts could displace hundreds of thousands and create a sprawling contamination zone that stretches across Galveston Bay.

This is because the Houston Ship Channel produces so many toxic chemicals. More:

“There are thousands of chemical tanks and many refineries with products that are so poisonous, so volatile, and so explosive that the result of this could be the greatest environmental disaster in the history of the planet,” O’Rourke said from his home in Houston on a recent afternoon. “Downtown Houston could be flooded with deadly chemicals, entire communities could be displaced, and Galveston Bay would go from the vibrant ecological system that it is to something catastrophic—a giant toxic pond.”

One more:

There are several proposals for protecting the Houston region from the kind of superstorm that leveled Galveston in 1900, in what remains the deadliest natural disaster in U.S. history. The most well-known plan is the Ike Dike, a seventy-mile-long, $23 billion to $31 billion coastal barrier and gate system designed to keep storm surge out of Galveston Bay. O’Rourke advocates, instead, for the “Galveston Bay Park Project.” The idea is to use dredged-up sand, rock, and mud to build a string of publicly accessible islands that would buffer the western side of Galveston Bay and the Ship Channel while also providing locals with new destinations for camping, fishing, migratory bird-watching, and marina access.

At an estimated cost of $5 billion to $7 billion, the project would be far cheaper than either the Ike Dike or the cost of recovering from an epic natural disaster. Proponents believe the project could be financed at the county and state level, ideally with the help of local industry, and be completed within five years. Unfortunately, O’Rourke said, officials haven’t completed the kind of environmental impact analysis necessary to move the proposal forward in that timespan. It’s as if, O’Rourke said, the city has utterly failed to heed “the great wakeup call” that was Hurricane Harvey.

“The ocean is getting hotter and the hurricanes are getting stronger,” he said. “At this point, we really are playing Russian roulette with the largest petrochemical complex in the United States.”

Read it all.The details are, uh, harrowing.

Laura is passing far enough to the east of Houston such that the Chernobyl scenario won’t happen there. However, Lake Charles, which is going to take the brunt of the storm, is also a petrochemical center. Here is the National Hurricane Center’s prediction for storm surge — that is, the tsunami of water that’s going to roll inland with this storm:

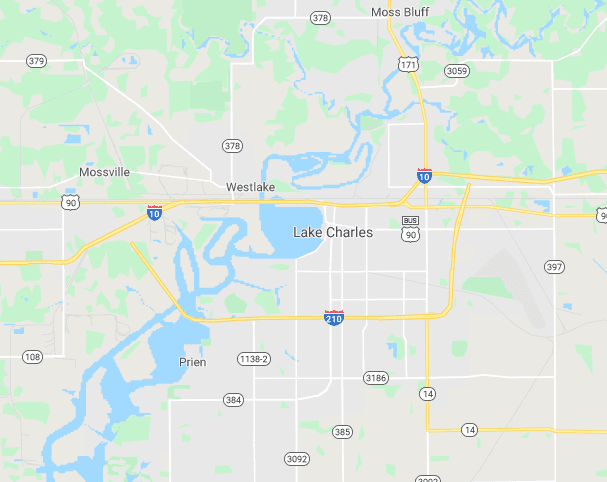

This is why they’re calling it “unsurvivable”: everything from the coast in to Lake Charles is going to be inundated with over nine feet of water. Note too how far the surge is going to go up the river, through Lake Charles. Here’s a close-up of the Calcasieu River and tributaries in Lake Charles — all of this is connected to the Gulf of Mexico:

About 75,000 people live in Lake Charles. It is 13 feet above sea level. It’s about 40 miles inland. Those numbers give you an idea of how low and flat that part of Louisiana is.