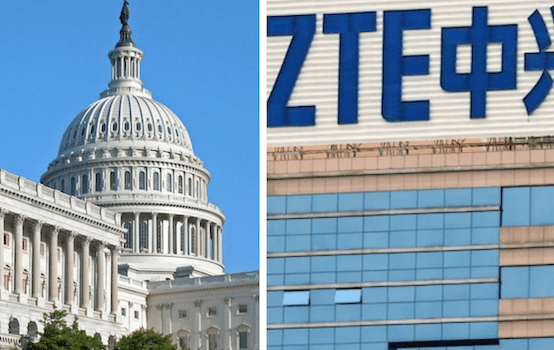

How D.C. Lobbyists Got China’s ZTE Off the Hook

On May 13, just days after Trump announced the United States would be leaving the Iran deal, Trump administration officials were making the Sunday talk show rounds with one clear message: if European companies continued to do business with Iran, the U.S. would slap sanctions on them. Ironically that same day Trump was also promising to help a company that had violated sanctions against Iran and North Korea literally hundreds of times.

Trump sealed it with a tweet: “President Xi of China, and I, are working together to give massive Chinese phone company, ZTE, a way to get back into business, fast. Too many jobs in China lost. Commerce Department has been instructed to get it done!”

Why is the Trump administration looking to punish our allies while rewarding one of the sanctions’ greatest violators? Part of the reason is undoubtedly that Trump wants to use ZTE as a bargaining chip in trade negotiations with China, as others have suggested. But there’s another explanation for Trump’s bipolar approach—an aggressive, extremely well-paid Chinese influence operation in Washington.

The problems for ZTE—the Zhongxing Telecommunication Equipment (ZTE) Corporation, one of China’s leading multinational telecommunications companies—began last March when the Department of Justice alleged that ZTE had violated the Export Administration Regulations by illegally exporting U.S. material to Iran and North Korea 380 times, for which they were fined by the U.S. Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) and placed on “probation” in a settlement. In April, BIS found that ZTE was in violation of the settlement, and on April 15 placed a Denial Order to halt the sale of any U.S. goods to ZTE, effectively crippling its ability to do business.

ZTE then did what many distressed foreign interests do when frustrated by the U.S. government—they hired a lobbying firm. Specifically, on April 18, just three days after the Denial Order was issued, ZTE hired Hogan Lovells to address “national security concerns and issues relating to April 15, 2018 denial order.”

Curiously, Hogan Lovells chose to report their representation of ZTE under the Lobbying Disclosure Act (LDA) rather than the much more stringent reporting requirements of the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA). The latter includes an exemption for firms that register under the less stringent LDA reporting requirements if they are representing private foreign corporations that are not connected to foreign governments or political parties. But it’s well known that ZTE isn’t a truly private company: in fact Congress has explicitly stated that ZTE and another Chinese telecommunications company, Huawei, “are not private companies.”

Hogan Lovells’ choice to register under the LDA and not FARA was made even more suspect when a firm they hired to help represent ZTE, Mercury Public Affairs, registered its work under FARA on May 24, more than a week before Hogan Lovells reported that it was representing ZTE. Had Hogan Lovells registered under FARA, everyone would have known nearly a month earlier that the firm was working to avoid punishment for an admitted sanctions violator.

While transparency may be lacking in this influence operation, lobbying firepower isn’t. Hogan Lovells reported that former senator Norm Coleman was working on the ZTE contract. Coleman is fresh off a victory lap following Trump’s withdrawal from the Iran deal, a move cheered by his client, the Embassy of Saudi Arabia.

Mercury Public Affairs brings firepower of its own in the form of Bryan Lanza, the former Trump advisor. Though Lanza has yet to personally register as a lobbyist for ZTA, he’s known for anticipating the Trump administration’s moves, and is currently lobbying to remove sanctions on Russia.

While we don’t know exactly how much money ZTE has spent on this lobbying operation (only Mercury has reported its fee of $75,000 per month), one thing is clear—it worked. On June 7, Reuters reported that a deal had been reached to lift the Denial Order and get ZTE back in business, albeit with steep financial penalties.

Congress has since intervened via the Senate’s version of the National Defense Authorization Act, which includes provisions to reintroduce penalties against ZTE. These provisions could be stripped out when the House and Senate meet to reconcile their two versions of the NDAA. However, including them is necessary as it sends a clear signal to China that they can’t violate U.S. sanctions, and a signal to President Trump that he can’t alienate U.S. allies while emboldening the influence operations of U.S. adversaries.

Sarah Jolley and Hannah Poteete are research fellows with the Foreign Influence Transparency Initiative at the Center for International Policy.

Comments