Hegemony Is a Choice

Graham Fuller marvels at how the U.S. presumes to “order” the world and then our leaders express surprise and outrage that our policies meet with resistance:

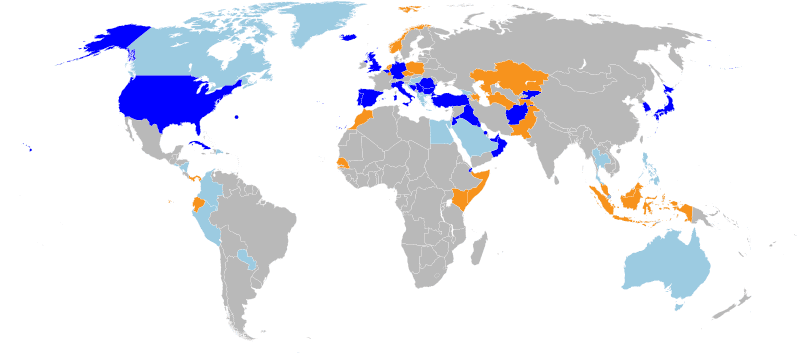

So, think about it: how can the United States exercise supreme and unchallengeable power around the world on the one hand, and yet simultaneously not provoke negative reactions from others? You can’t be the most powerful player on the block — or what the U.S. military often tellingly calls its global footprint” — and yet not expect strong reactions from those affected by it.

Again, I’m not even trying to assess how good or bad, how generous or harsh, how wise or foolish U.S. actions have been. It’s simply the perception in our eyes that we are nearly always the aggrieved party facing negative or ungrateful reactions.

One of the things that illustrates Fuller’s point is the interventionist rhetoric used to sell wars of choice. The U.S. wages mostly wars of choice, but our leaders routinely cast them as conflicts that have been “forced” upon us by others. This may be the only way to make the bludgeoning of smaller nations by the world’s preeminent power seem politically acceptable. George W. Bush absurdly claimed that the U.S. would use force in Iraq only as a “last resort” and that the U.S. had “done everything we can to avoid war” when the U.S. was just weeks away from launching an aggressive and illegal war to “disarm” a government that did not possess the weapons it was accused of having. While many interventionists are quick to demand military action to head off possible, future threats that do not and may never exist, there is still a pretense that the U.S. is reluctant to use force and does so only under duress. The U.S. simultaneously claims to be a defender of order while reserving to itself the right to disrupt and violate that order whenever it deems it “necessary.”

When the U.S. presumes that the ordering of the world is its responsibility and that it has the right to take aggressive military action wherever it perceives a potential threat, our leaders shouldn’t be surprised when other states doubt our intentions and question our motives. Our ambitious strategy of dominance invites and provokes challenges, and because our leaders have defined our interests so broadly they will view any challenge anywhere as a “threat” to the maintenance of U.S. hegemony everywhere. As Fuller observes, “Hegemony finds any challenge insufferable. It has been an integral part of Washington’s worldview for many decades now.” The mere existence of governments that do not yield to U.S. preferences is treated as intolerable, and that is why the destructive option of regime change continues to be considered as an acceptable “solution” to the challenges these governments present.

The U.S. faces so many “challenges” because our leaders have chosen to pursue policies that put us on collision courses with many other states and groups. We can and should choose differently. If we stopped looking for new enemies to confront in every corner of the world, we would find that America doesn’t face nearly as many threats as our leaders have claimed.

Comments