Exorcising George McGovern

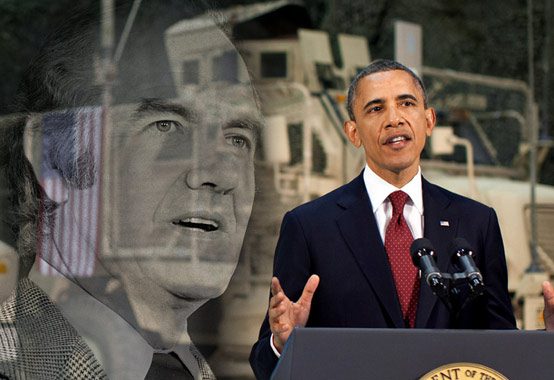

Mitt Romney is banking on the traditional Republican advantage in defense to help him defeat President Barack Obama this November.

In his speech at the Citadel last October, he posed a stark choice for voters: “If you do not want America to be the strongest nation on Earth, I am not your president. You have that president today.” Romney’s website lists among Obama’s many “failures” the hollowing-out of the U.S. military under his watch.

This Republican strategy of painting Democrats as soft on defense has a long pedigree in American politics. The question is, will it still work? Romney shouldn’t bet on it.

Since the epochal election of 1972, in which anti-Vietnam War sentiment rocketed the dovish South Dakota Senator George McGovern into orbit as his party’s ultimately unsuccessful nominee for president, the Democratic Party has been attacked by the GOP as soft on defense.

Even though the next Democratic president, Jimmy Carter, had robust national-security credentials as a former nuclear submarine officer and is widely credited with beginning the military build-up that helped Ronald Reagan end the Cold War, his administration could not erase the image that Democrats were national-security weaklings and bunglers, especially after the failed Iran hostage rescue attempt.

Massachusetts governor Michael Dukakis’s efforts to burnish his stature as a warrior by visiting the M-1 tank plant in Lima, Ohio in 1988 backfired after some in the media observed that the tank commander’s helmet he donned for the photo-op made him look less like General Patton than Mickey Mouse.

And Bill Clinton, who managed to defeat World War II hero George H.W. Bush in 1992 with the battle-cry that “it’s the economy, stupid” was subsequently dismissed by a general as a “pot-smoking, draft-dodging, skirt-chasing commander in chief.”

In 2004, Vietnam War veteran Massachusetts Sen. John F. Kerry was unsuccessful in unseating another child of the ’60s, George W. Bush, who led America into an unsuccessful war in Iraq under the false pretenses of preventing Saddam from getting nuclear weapons. Kerry discovered to his chagrin that even his Bronze Star and Purple Heart did not trump his opponent’s stateside service in the Texas Air National Guard.

But the election of Barack Obama in 2008, at a time when widespread war-weariness had finally set in, may have finally broken the mold that casts Republicans as strong on defense and Democrats as war wimps.

Despite winding down the U.S. military presence in Iraq and setting the stage for a coalition withdrawal from Afghanistan, Obama has done these things in such a way that it is hard to say he is cutting and running. Polls show that the public approves of both of these actions.

Moreover, this Democratic president hardly seems skittish about using force: he has waged the drone war with al-Qaeda with much more vigor than his Republican predecessor (just ask the Pakistanis), he doubled down on the U.S. commitment in Afghanistan at a time when many thought it was a bad bet, he stiffened NATO’s spine to provide air support for the successful anti-Gaddafi uprising in Libya, and most importantly he put the big coon skin on the side of the barn with the daring Navy SEAL strike against Osama bin Laden in Pakistan.

Not surprisingly, it is proving hard for Obama’s Republican opponents to challenge his national-security credentials from a reasonable perspective. That has led them to embrace increasingly cloud-cuckoo land critiques of the administration’s national-security posture.

Exhibit A was former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich’s warning during the Republican primaries that Obama was ignoring the threat of an electromagnetic pulse from a nuclear warhead exploded high over the United States, an attack he believed could end life as we know it. This diabolical plan, however, depended on an adversary having both reliable nuclear warheads and intercontinental ballistic missiles, a combination that neither North Korea nor Iran possess or are soon likely to get.

In another howler, Romney recently castigated Obama for coddling the Russians by allowing them to mount intercontinental ballistic missiles on their strategic bomber force under the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty. But Romney needs a remedial class in Nuclear Strategy 101: bombers do not carry ICBMs.

This gaffe has done little to bolster the former Massachusetts governor’s credentials to be the next commander in chief. As the New York Times has reported, many Republican foreign-policy stalwarts like Colin Powell and Brent Scowcroft are uncomfortable with Romney’s hard-line anti-China rhetoric and uncompromising pro-Israel stance and have so far withheld their endorsements. These traditional realists’ discomfort with him is no doubt increased by the fact that many of the Republican nominee’s foreign-policy advisers are recycled neoconservatives from the last administration, such as Eliot Cohen, Aaron Freidberg, Eric Edelman, Dan Senor, and Dov Zakheim.

Governor Romney’s lambasting of Obama’s inaction in Syria will likely not gain much traction with a war-weary American public that does not see any strategy for quick victory there. According to a recent Pew Research Center poll, only 25 percent of Americans agree with him that the United States ought to take a more forward-leaning stance in that conflict.

Governor Romney’s lambasting of Obama’s inaction in Syria will likely not gain much traction with a war-weary American public that does not see any strategy for quick victory there. According to a recent Pew Research Center poll, only 25 percent of Americans agree with him that the United States ought to take a more forward-leaning stance in that conflict.

Romney promised the cadets at the Citadel that “This century must be an American Century,” adding that in “an American Century, America leads the free world and the free world leads the entire world.” In his view of divine providence, “America is not destined to be one of several equally balanced global powers.” While he didn’t deliver these bromides in a West Texas drawl, Romney sure sounds like the last Republican president who thought Jesus would be his co-pilot as he drove the country into the second American Century.

But if after two failed wars and a wrecked economy this warmed-over Project for a New American Century bombast is the best the GOP nominee can offer, the incumbent can be confident that the 2012 election will not turn yet again upon doubts about whether a Democrat can adequately defend the country.

Michael C. Desch is co-director of the Notre Dame International Security Program.

Comments