Your Story About Yourself

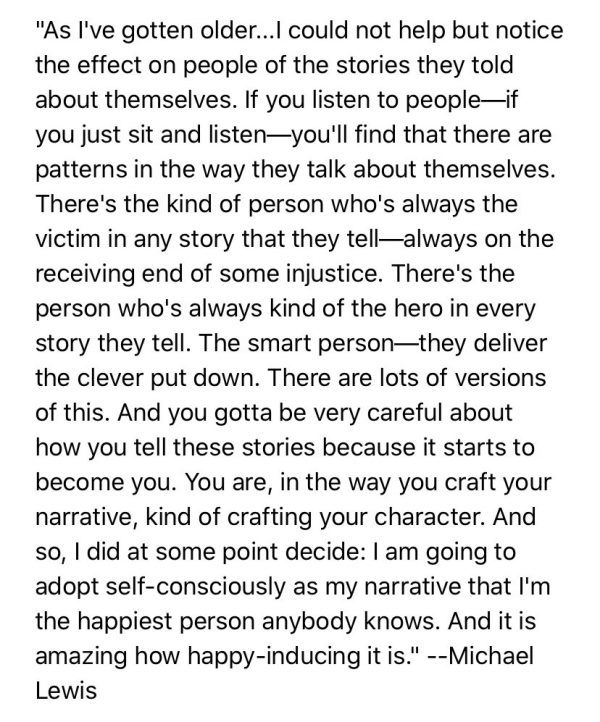

This has been going around Twitter. It’s from a podcast interview Tim Ferriss did with the great nonfiction writer Michael Lewis:

That’s really something, isn’t it? I’ve often heard it said that we live not so much by principles, but by stories. In my book How Dante Can Save Your Life, I wrote:

Neuroscientists have found that the telling of a story, no matter how simple, lights up parts of our brains that lie dormant when we merely process language. In fact, research has shown that the brain reacts to stories in the same way it responds to actual events. When a story fully enters into your imagination, it is as if you experience it yourself. The more vivid and sensual the descriptions within a story, the more powerfully its lessons, moral and otherwise, lodge in the brain.

Annie Murphy Paul, writing about these discoveries in the New York Times, observed: “Reading great literature, it has long been averred, enlarges and improves us as human beings. Brain science shows this claim is truer than we imagined.”

Here’s a link to that 2012 piece by Annie Murphy Paul. In it, Paul continues:

Raymond Mar, a psychologist at York University in Canada, performed an analysis of 86 fMRI studies, published last year in the Annual Review of Psychology, and concluded that there was substantial overlap in the brain networks used to understand stories and the networks used to navigate interactions with other individuals — in particular, interactions in which we’re trying to figure out the thoughts and feelings of others. Scientists call this capacity of the brain to construct a map of other people’s intentions “theory of mind.” Narratives offer a unique opportunity to engage this capacity, as we identify with characters’ longings and frustrations, guess at their hidden motives and track their encounters with friends and enemies, neighbors and lovers.

I wonder how these findings apply to the self-narratives we employ, in the sense Michael Lewis means.

I’m thinking of a friend whose stories about herself always, always have her being victimized by someone, or by life. I used to think wow, people sure are mean to her or she sure has drawn a bad hand. But as I got to know her better, and as I began to see her interact with mutual friends, I came to see that her perception was very far from how things actually were, at least in the interactions with which I had personal knowledge. Long story short: I learned eventually that my friend had had a traumatic, emotionally abusive childhood, and had come to expect that people would mistreat her. She always seems to be looking for the hidden angle, for the way others are trying to put her down. If you say to her something like, “Martha [not her real name], you did well. They really liked you!”, she will respond that if I only saw how things really were, I would know that deep down, those people hate her. And if I push back, and insist that no, they really do like her, and that she is imagining that they don’t, she will accuse me of demeaning her judgment, and putting her down like all those other people do.

I talk about this in the present tense, but truth to tell, I have intentionally grown distant from “Martha” over the past few years. It’s too exhausting to be her friend. You get tired of all the neurosis. I’m sure she thinks, “See, I was right about Rod. He hates me too! They all do!” In fact, Martha’s is a sad case of self-sabotage. She has a good heart, and certain gifts, but the story she has spent a lifetime telling about herself — that she is one of life’s victims — is one that she eventually lived into.

Thinking about poor Martha, I find it puzzling that she could never accept good news about herself. I did not know her when she was younger. I don’t know if there was ever a time when she might have been able to change her story, to refuse the story that she had received from her abusive childhood. Talking to a guy who had been part of Martha’s circle at one time, he told me that he quit hanging out with her because he got tired of hearing her gripe all the time about all the people who were doing her wrong. Indeed, as I’m sitting her typing, I’m thinking of happy stories Martha has told about herself, and how often they end with some form of, “… but that didn’t last, because [somebody else betrayed or hurt me].” In fact, I know that she has probably driven more than just that one person away from her, because she lived in such a way as to make her negative self-narrative come true. I know all too well from personal experience that suggesting to Martha that she has it wrong, that she is not a victim, that life is not a dark as she thinks it is — that gets absolutely nowhere. It’s as if she is so dependent on the narrative of herself as Victim that she fears surrendering it would unleash chaos. At least the world makes sense in that narrative — and her sense of needing to control the world matters more than wanting to be happy and at peace in it.

And you know, I am certain that Martha doesn’t realize that her narrative is a construal. She cannot comprehend that she might be seeing things incorrectly. She thinks that she’s living in truth, but in fact she’s living within a story she was written for herself. A little postmodernism would do Martha a lot of good.

Question to the room: is there a pattern in the way you talk about yourself? Ever thought about it? I haven’t ever thought about it with regard to myself. If I had to guess, my self-narrative usually involves me wandering into a situation in which I have some epiphany — I met the most amazing person/saw the most amazing thing/tasted the most amazing dish — that compelled me to rethink my approach to life in some way, or at least reaffirmed gratitude for the thing I was shown. My stories about myself generally construe myself as a Pilgrim of some sort: someone who sees life as a journey, along which I meet enchanted people, mysterious castles, wicked dragons, and so forth, and find some way to discern meaning from those encounters, and integrate those them into my own perspective. Sometimes in the telling of these stories I am a Pilgrim who is also a “fortunate fool.” There is often a quality of gentle self-abasement to my stories, which sometimes signals that I see myself as unworthy of this knowledge or these experiences. I think the sense of naive wonder I bring to these tales must irritate people — I would probably be irritated if I saw that in others — but for better or for worse, that’s who I am.

But at other times — when I am not so gentle in my self-abasement — means that I was lucky enough to discover what a fool I had been, so that I would not be that same fool in the future if I could help it. There is a quality of confession and atonement in those self-narratives, and I am quite conscious of it. When I tell the story of how I supported the Iraq War, I try to be hard on myself, because I don’t want to be that man again, and I want my listeners to understand how we can lie to ourselves even when we think we are being brave and truthful. When people ask me how I lost my ability to believe as a Catholic, I tend to focus more on my own idolatry of the Catholic Church than on the bad things the Church did. I do that because I want to own my sins, and my part in that painful episode — and do not want to repeat it, and do not want my listeners to set themselves up as idol-worshipers. Auden said (you’ll see the full quote below) that when we are falsely enchanted, we end up wanting to possess the object of enchantment, or wanting to be possessed by it. That’s how I was with Catholicism: I wanted it to possess me. That’s my fault, not Catholicism’s — and that’s the story I want to tell all Christians. Because it could happen to them too. Anything that is not God, but that we wish to possess or have possess us, can become an idol. This is a hard, hard lesson my pilgrimage has taught me.

There’s no doubt that Orthodox Christianity has played a big role in helping me not only to sharpen my sense of myself as a pilgrim, but also as a fortunate fool. Longtime readers will know that within about a single decade — from 2001 till around 2013 — I lost the three frames that helped me understand the world and my place in it. I lost my Catholic faith, I lost my faith in conservative politics, and finally, I lost the illusions I had about my family back in Louisiana (which I had also idolized, in the same way I idolized Catholicism). You can see why Dante’s Commedia was such a godsend! What it taught me to see — and this was backed up by Orthodoxy — was that everything we experience can be an opportunity for deeper conversion, for a more profound dying to self, and awakening to God.

I have always been a seeker and a pilgrim, but the tragedy of that decade of my life made the story darker, but maybe also filled it with more light. I’m not sure, because I don’t stand outside of myself. Just this morning I found this quote from W.H. Auden, and it deeply resonated with the pilgrim inside me:

The state of enchantment is one of certainty. When enchanted, we neither believe nor doubt nor deny: we know, even if, as in the case of a false enchantment, our knowledge is self-deception.All folk tales recognize that there are false enchantments as well as true ones. When we are truly enchanted we desire nothing for ourselves, only that the enchanting object or person shall continue to exist. When we are falsely enchanted, we desire either to possess the enchanting being or be possessed by it.We are not free to choose by what we shall be enchanted, truly or falsely. In the case of a false enchantment, all we can do is take immediate flight before the spell really takes hold.Recognizing idols for what they are does not break their enchantment.All true enchantments fade in time. Sooner or later we must walk alone in faith. When this happens, we are tempted, either to deny our vision, to say that it must have been an illusion and, in consequence, grow hardhearted and cynical, or to make futile attempts to recover our vision by force, i.e., by alcohol or drugs.A false enchantment can all too easily last a lifetime.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.