What Do Integralists Want?

If you don’t follow the world of right-of-center Christian intellectuals, you might not have heard of the integralists, proponents of a 19th century political theory that, broadly speaking, conceives of a polity based on Catholic authority.

You might have seen them mentioned if you read the New York Times story on Sunday about right-wing American intellectuals and Hungary. There was this passage, centering Harvard law professor Adrian Vermeule, who has become the leader of American integralists:

New approaches were needed. And Vermeule, a recent convert to Catholicism who is considered one of the most limber legal scholars of his generation, was in a position to provide them. Recently, in a spate of articles published in national magazines and small conservative quarterlies, Vermeule has laid out a methodology for halting what he regards as the relentless advance of the liberal “creed.” In place of originalism — a theory espoused by conservative judges which holds that the meaning of the constitution is fixed — Vermeule proposed “common-good constitutionalism”: reading “into the majestic generalities and ambiguities” of the Constitution to create an “illiberal legalism” founded on “substantive moral principles that conduce to the common good.” Vermeule also offered a complementary theory of the administrative state, a topic on which he has written a number of books, that could be used to promote those moral principles. Those occupying positions of power in government administration could have a “great deal of discretion” in steering the ship of bureaucracy. It was a matter of finding a “strategic position” from which to “sear the liberal faith with hot irons.”

Even many of those interested in Vermeule’s ideas consider him extreme; some suspect him of wanting to impose a Catholic monarchy on America. (Vermeule declined to comment for this article.) But scholarship based on Vermeule’s ideas is starting to trickle out, some of it reshaping his concept as “common-good originalism.” Josh Hammer, the opinion editor of Newsweek, has argued that the emphasis on “general welfare” in the preamble to the Constitution, a synonym for the Greco-Roman concept of the “common good,” is a part of America’s heritage that is overshadowed by our focus on individual liberties. Originalism, with its insistence on “one true meaning,” has turned out to be “morally denuded,” Hammer told me. “Is that the end unto itself, or is it something a little greater?” he said. “It’s a viable political concept to care about national cohesion.”

Samuel Goldman, a conservative political theorist who directs the politics and values program at George Washington University, concedes that the historical record supports the view that “many, though not all, of the American founders really did imagine the U.S. as a sort of Christian nation state, in which public institutions would play a significant role in promoting virtue and be committed to specific religious doctrines. It didn’t work out that way, because even at the time, the population was too diverse, the institutions were too precariously balanced to permit it.” He went on to say that what the postliberals are doing seems strange because “it’s a trip back into an intellectual world that no longer exists.”

For Vermuele, promoting “substantive moral principles” might allow the state to intervene in areas like health care, guns and the environment, where “human flourishing” would take priority over trying to divine the 18th-century meanings of terms like “commerce” and “bearing arms.” Abortion would be illegal. But the outcomes of such policies would not always be the expected conservative ones. Vermeule recently argued in favor of a Covid-19 vaccine mandate, on the grounds that the health and safety of the community was necessary for the common good.

Governing for the common good would be the “final rejection” of the neoliberal dogma that “if you leave individuals to seek their own ends, you’ll necessarily build a good society,” Sohrab Ahmari, the former opinion editor of The New York Post, who says he is launching a new media company, told me. Ahmari, a recent convert to Catholicism, is one of Vermeule’s most visible allies and has become practically synonymous with a self-consciously pugilistic right. He urged conservatives in a 2019 essay to approach the culture war “with the aim of defeating the enemy and enjoying the spoils in the form of a public square reordered to the common good and ultimately the Highest Good,” a phrase that has enjoyed a long half-life. “I don’t want to turn this into a Catholic country,” Ahmari told me when I met him earlier this year. But he counts himself among those who believe conservatism has failed because it insists that the only kind of tyranny “comes from the public square and therefore what you should do is check government power.”

The one thing that everyone under the broad category of “postliberalism” agrees on is that we have probably reached the end of the road with classical liberalism. As Deneen observed in his 2018 book, liberalism has beached itself because it succeeded so well in creating a world in which the individual is liberated from anything standing in the way of his individual choice. Turns out you can’t run a society like that. So now what?

What’s more, postliberals generally agree that the claim of liberal neutrality is a false one. Eventually, lines have to be drawn — and liberalism almost always draws them in the same way. The Catholic writer James Kalb wrote an excellent book on this, and talks about it in this 2009 interview. In the piece, he says, “Liberalism is progressive, though, so its demands keep growing. It eventually rejects all traditional ways as illiberal and becomes more and more radical.” Eventually it has to deny all traditions and traditional institutions as oppressive.

Kalb says liberalism isn’t all bad; it simply has to be subordinated to a shared conception of the Good.

Q: You argue that religion can be the unifying force that offers resistance to advanced liberalism, and that the Catholic Church is the spiritual organization most suited to that task. Why do you think so?

Kalb: To resist advanced liberalism you have to propose a definite social outlook based on goods beyond equal freedom and satisfaction.

A conception of transcendent goods won’t stand up without a definite conception of the transcendent, which requires religion. And a religious view won’t stand up in public life unless there’s a definite way to resolve disputes about what it is.

You need the Pope.

Catholics have the Pope, and they also have other advantages like an emphasis on reason and natural law. As a Catholic, I’d add that they have the advantage of truth.

Note well, I don’t know if Kalb is an integralist, but he’s right about the nature of the Good as the basis of a postliberal political order. The problem, though, is that we in the United States are a highly pluralistic nation, in which Catholics are a minority, and the number of Catholics willing to submit their lives to the teaching authority of the Church is very small. Another problem: unlike when Kalb wrote that in 2009, Catholics now have a pope who does things like appoint Jeffrey Sachs to the Pontifical Academy.

The grand problem facing postliberals of the Right is that we can agree that we need to base politics on an authoritative and shared conception of the Good, but we have no realistic idea how to do that in postmodernity. The integralists — at least the ones who have made themselves heard on the fringes of the American Right — have an idea of how to do it … but it’s completely unworkable. Earlier on Wednesday, I recorded a TAC podcast with Sohrab Ahmari, a leading American integralist, in which we explored these ideas. I held off posting this blog entry until after doing the podcast, in hope that I would have some of my questions clarified by it. It was a fine conversation, but I left it as skeptical as I came in.

To be fair, Catholic integralism is an appealing and coherent way of thinking about politics. Here, from The Josias, the leading integralist website, is a short definition of integralism:

Catholic Integralism is a tradition of thought that, rejecting the liberal separation of politics from concern with the end of human life, holds that political rule must order man to his final goal. Since, however, man has both a temporal and an eternal end, integralism holds that there are two powers that rule him: a temporal power and a spiritual power. And since man’s temporal end is subordinated to his eternal end, the temporal power must be subordinated to the spiritual power.

Why is this appealing? Because they’re right that you can’t ultimately separate politics from concern with the ends of human life. Liberalism tries to do this, but it conceals within it a view of the proper end of human life. I’m interested in what integralism has to contribute to the debate, because from what I have seen, at their best, they are good at thinking these things through. As was clear in the conversation with Ahmari (which will be posted later this week), the major weak spot in my position as someone who identifies as postliberal is that I agree that liberalism as we know it has exhausted itself, but I don’t have a suggestion for what should replace it. The integralists certainly do — and their preferred order reminds me of why as flawed as liberalism is, I am not eager to give it up entirely. Let me explain.

Catholic integralism — the idea that the political order should be subordinated to the Catholic Church — is a complete non-starter in America. For that matter, it’s hard to think of a single country in the Christian world where it would stand a chance. Poland is not an integralist state, but it’s probably the place on earth where political Catholicism is the farthest advanced. I’m not a Catholic, but I generally like what the Law & Justice government there is doing. That said, almost all the Poles I’ve talked to, especially young Catholic ones, believe that political Catholicism is a doomed project over time, because so many of the younger postcommunist generation are falling away from the faith. As I’ve said here many times, Poles tell me that within a decade or so, they expect their own country to go the way of Ireland: into a near-total collapse of the Catholic faith. Understand what I’m telling you: these aren’t secularists who want to see this happen; these are serious young Catholics. Father Wlodzimierz Zatorski, a well-respected Benedictine (who died of Covid last year), told me in 2019 that the only long-term hope for the Church in Poland was through establishing strong Benedict Option communities, and re-evangelizing from there.

If political Catholicism is in trouble in Poland, where almost everybody is Catholic, at least nominally, how on earth is it ever going to triumph in the United States, where Catholics (nominal and serious) only number about 20 percent of the population? And of that number, how many of them would be willing to surrender American liberties for a reactionary 19th century ideal establishing the Catholic Church, and making the State subordinate to it? I bet you could fit all of them into Adrian Vermeule’s backyard in Cambridge, Mass.

In any case, the vague definition of integralism on the Josias doesn’t sound threatening. It’s when you start asking what that means in real life that it turns freaky. Normally, intellectual engagement is something to be enjoyed and engaged. There are plenty of non-Catholics who are interested to figure out a workable future under the condition of postliberalism, and would like to talk it all out. Not these cats. See, this is the thing that you must not do — ask what this would mean in real life. It makes our integralists mad. They blow up online, and sneer, act all indignant, and say that you must be one of those David French types for asking. It’s a silly act, but it tells us something important about them. If they thought that their program would be appealing to people, they would be eager to lay it out and try to win converts. They seem to think that they are going to insult and sh*tpost their way to power. They are very, very good at making enemies, especially of the people on the Right who are their natural allies.

But would you want to let any of these folks close to power? Not if you aren’t Catholic — and not if you are a Catholic who doesn’t believe the Papal States under Pius IX were the foothills of the New Jerusalem.

Think I’m kidding? Here’s Adrian Vermeule, their intellectual godfather, in a 2019 post calling for the US to open its southern border to Catholic migrants, as a first step towards dissolving America and creating a globalist Catholic empire. He concludes:

As the superb blog Semiduplex observes, Catholics need to rethink the nation-state. We have come a long way, but we still have far to go — towards the eventual formation of the Empire of Our Lady of Guadalupe, and ultimately the world government required by natural law.

Now, this is mostly a joke, I think. Vermeule, the Yankee archreactionary, is saying that under his ideal plan, migration to America would favor black and brown people, and the poor, who identify as Catholic. He is trolling the libs. But like many integralists, he really does believe that Catholic principles require a world government overseen by the Catholic Church. Good luck selling that to American Protestants. For that matter, good luck selling that to American Catholics. And if he wasn’t joking about opening the southern borders and dissolving the American nation-state, this is important information for us to know.

Vermeule believes, by the way, that Catholics have no choice but to be integralists. In this short presentation at Notre Dame in 2019, he quotes Pope Leo XIII saying that in America, the political order must not be separated from the religious order, the “perfect society” (Vermeule’s words) of the Catholic Church:

Here, from the book Integralism: A Manual of Political Philosophy, by Thomas Crean and Alan Fimister, is what the term “perfect society” means:

I’ll post more from this illuminating book later.

Vermeule calls papal teaching on integralism “irreformable.” Whether it is or isn’t is not a question for me to take up, but it does indicate how seriously he takes this. At that same conference, Gladden Pappin, an integralist academic and close collaborator of Vermeule’s praised the Chinese Communist regime for having a ministry that clearly lays out what the spiritual goals of a society should be — this, by contrast to the US, which has no such office:

He thinks the US should have such an office, and that it should be the Catholic Church. How do we get to that place in a minority-Catholic country, in which the Catholic Church is hemorrhaging members? They don’t tell us.

Well, actually, Vermeule does tell us. Until such time as they can take over, he told the Notre Dame audience, integralist Catholics ought to march through the governing institutions, with the long-term goal of overturning liberalism:

He is admirably clear about what he’s after. But what role would Jews, Protestants, Orthodox, and non-Catholics have in such a regime?

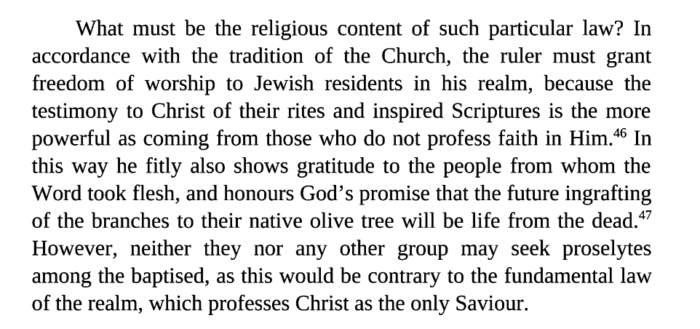

For these and other answers, turn to the Crean and Fimister book, which is a bit dry but admirably clear in its explanations of integralism. I read it here, for free. Here are some quotes; I’m sorry for the presentation, but I could not copy and paste, according to the format:

More:

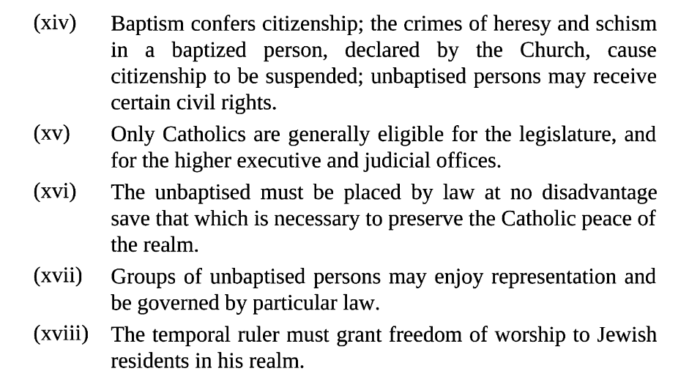

Got that? Integralism teaches that only baptized Catholics may hold political power, and that they must exercise it in accordance with Catholic teaching. Not quite sure how that’s going to work in the United States of America, but let’s go on:

This is a critical point. It is precisely what was at issue in the infamous 19th century case of Edgardo Mortara, a Jewish child who had been secretly baptized by the family’s Catholic housekeeper. As the Mortara family lived in the Papal States, in which the pope was also the temporal ruler, Pius IX dispatched agents to seize the child so he could be raised with the Catholic education to which he was entitled. He ended up becoming a priest, and did not regret his fate — something that is easy to imagine, but in no way obviates or lessens the cruelty of his taking, any more than it lessened the injustice of those pioneer children kidnapped by Indian tribes and raised as Indians, who preferred as adults to remain with the Indians.

When you ask the integralists what they would do to guarantee that the Mortara case wouldn’t happen again if they come to power, they sometimes become indignant, as if raising the issue was rude or irrelevant. It’s not, though. It is rather unlikely that a situation like this would arise again, but it is also extremely important that the Church renounce its “right” to do this monstrous thing. The fact that integralists will not explicitly renounce the Catholic Church’s right to act in this way is a tell. Many conservatives rightly object to the State (e.g., the state of Washington) retaining the right to seize transgender minors from their families so the kids can have sex-change medical treatments. I’m not sure why we would be eager to embrace a system that gives the Catholic Church the right to seize baptized children from their non-Christian parents. I wish the integralists would tell us instead of getting angry at the perfectly reasonable question.

According to integralism, slavery is not ruled out. The slave simply must have his servitude comport with the law:

According to integralism, all Christian rulers must be subject to the Roman see:

It’s as if the East-West schism and the Reformation had never happened. This is one of those points where you can admire integralism for its audacious logic, but also know that it doesn’t have a snowball’s chance of realization in the world as it actually is.

Here is integralism (insofar as Crean & Fimister represent it accurately) claiming that the ruled have no say over who rules them:

As broken-down and beaten-up as liberalism is, do we really want to trade it for a system that says government does not depend on the consent of the governed? I don’t, and I am confident that only a vanishingly small number of American Catholics would.

So the people have no right to choose their own leaders, but it might be prudent to let them act as if they did. Got it. As for religious liberty, here’s what the temporal ruler should and should not do:

Here’s more:

Right. More:

By forbidding those people who aren’t Catholics from voting, the temporal ruler will encourage people to become Catholic. That’s the idea. It doesn’t seem to have occurred to the integralists that this would stir up rebellion by those who do not want to be ordered around by the Catholic Church, or be made second-class citizens in their own country.

So, what kind of role would people like me and other non-Catholics have to play (“Christendom,” in the integralist definition, does not include Orthodox and Protestant countries)? From the Catholic perspective, Orthodox are schismatics — and should have my citizenship suspended until I see reason and return to Catholicism (or, in the case of my youngest child, baptized Orthodox, leaves her baptismal faith and submits to the Pope):

More:

It’s not like they won’t give unbaptized people anything. The temporal ruler owes them nothing, but he might give them “certain civil rights,” though certainly they cannot be citizens, even if they were born in that country:

Jews, though, do get a free pass to worship, but they had better not seek converts:

This is from a summary of that particular chapter:

What about Muslims? Mormons? Buddhists? Are they entitled to freedom of worship? Doesn’t seem so. I don’t want to live in a polity where these people, despite their theological errors, are not granted freedom to worship.

Anyway, I encourage you to read the entire book. It makes it very clear why integralists like to keep their discussions of what they believe at a very general level, using inoffensive terms like “political Catholicism” (Sohrab’s preferred description), “common good conservatism,” and saying that they seek a political order based on helping man achieve the Good. Those things all sound good, but the devil is very much in the details.

Again: I fully concede that the weakness of my position is that I don’t have a clear, concise goal for what kind of political order should replace liberalism (and by “liberalism,” I mean classical liberalism, not simply the philosophy of the Democratic Party). Integralism does offer a clear, concise replacement; so does orthodox Marxism. Neither one, though, would or should be tolerated by people who cherish liberty — their own, or that of others. Any attempt to impose integralism, especially on a polity that is majority non-Catholic, would cause civil war. I had not realized until I read the Crean & Finster book after our podcast taping, that integralism is not interested in the consent of the governed. That being the case, it’s easier to understand why Vermeule believes, or seems to believe based on his Notre Dame remarks, that integralists ought to bide their time and infiltrate the institutions of government, until the moment when … what?

This is the primary weakness of the integralist position: it is utterly unrealistic in a post-Christian world. If the integralists get power, and think they can re-Christianize the lost lands of Christendom by executive action, they will find their sovereigns treading the same paths as Julian the Apostate, and King Canute. Second, I find it impossible to believe that these men are anything but appalled by many of the actions of Pope Francis. But they hold their tongues, perhaps out of respect for the office, but also because it’s very hard to convince people that the political order ought to be subject to the will of the Roman pontiff when the Roman pontiff is a font of confusion and instability.

Having read Crean & Finster, I understand better why so many of the leading integralists treat those who question them with sneering disdain. If most people knew what they really believed, they would run screaming the other way. It’s a lot easier to sh*tpost on Twitter, accuse people who don’t accept the integralist revelation of being David French acolytes, and so forth, all to the hurrahs and attaboys of the Very Online. But here in the real world, Christians and other conservatives who would like to construct a viable alternative to decaying liberalism had better figure out how to do so in a way that can accommodate pluralism. The more I read about integralism, and listen to integralists, and see the way integralists treat those who question them, the more I run smack into a big reason why liberalism arose in the first place: to provide a way for people who disagree on the nature of the Good to live together in relative peace.

The other day, Sohrab posted this tweet, which I include below with my comment:

Are Burkean conservatives and classical liberals gay as geese now, and us non-integralists are too sinful to see it? https://t.co/tThBcjn0iv

— Rod Dreher (@roddreher) October 25, 2021

At the risk of being called a big old homo by the integralists, let me put a word in for a Burkean approach. Here’s something John Michael Greer wrote about Burke:

The foundation of Burkean conservatism is the recognition that human beings aren’t half as smart as they like to think they are. One implication of this recognition is that when human beings insist that the tangled realities of politics and history can be reduced to some set of abstract principles simple enough for the human mind to understand, they’re wrong. Another is that when human beings try to set up a system of government based on abstract principles, rather than allowing it to take shape organically out of historical experience, the results will pretty reliably be disastrous.

What these imply, in turn, is that social change is not necessarily a good thing. It’s always possible that a given change, however well-intentioned, will result in consequences that are worse than the problems that the change is supposed to fix. In fact, if social change is pursued in a sufficiently clueless fashion, the consequences can cascade out of control, plunging a nation into failed-state conditions, handing it over to a tyrant, or having some other equally unwanted result. What’s more, the more firmly the eyes of would-be reformers are fixed on appealing abstractions, and the less attention they pay to the lessons of history, the more catastrophic the outcome will generally be.

That, in Burke’s view, was what went wrong in the French Revolution. His thinking differed sharply from continental European conservatives, in that he saw no reason to object to the right of the French people to change a system of government that was as incompetent as it was despotic. It was, the way they went about it—tearing down the existing system of government root and branch, and replacing it with a shiny new system based on fashionable abstractions—that was problematic. What made that problematic, in turn, was that it simply didn’t work. Instead of establishing an ideal republic of liberty, equality, and fraternity, the wholesale reforms pushed through by the National Assembly plunged France into chaos, handed the nation over to a pack of homicidal fanatics, and then dropped it into the waiting hands of an egomaniacal warlord named Napoleon Bonaparte.

More:

The existing laws and institutions of a society, Burke proposed, grow organically out of that society’s history and experience, and embody a great deal of practical wisdom. They also have one feature that the abstraction-laden fantasies of world-reformers don’t have, which is that they have been proven to work. Any proposed change in laws and institutions thus needs to start by showing, first, that there’s a need for change; second, that the proposed change will solve the problem it claims to solve; and third, that the benefits of the change will outweigh its costs. Far more often than not, when these questions are asked, the best way to redress any problem with the existing order of things turns out to be the option that causes as little disruption as possible, so that what works can keep on working.

That is to say, Burkean conservatism can be summed up simply as the application of the precautionary principle to the political sphere.

The precautionary principle? That’s the common-sense rule that before you do anything, you need to figure out whether it’s going to do more good than harm.

This is not as potent, clean, or logical as the ideology laid out by integralism. But it has the great advantage of not reducing people, in all their messiness, to abstractions. It is true that all societies have an idea of the Good that is reflected in lawmaking. You can’t get away from it. It is also true that liberalism is not neutral, that the hidden hand within liberalism tends to favor some things as goods and not others (for example, it inevitably emancipates the individual from all unchosen obligations). Again, though, what is the alternative? The answer is not clear, and working it out is going to require a great deal of thought and collaboration on the Right, among various factions. James Kalb is right about needing a thick sense of the Good rooted in religion, but given the woebegone state of Christianity (and not just Catholic Christianity) in the West, it is extremely hard to see how we arrive at that necessary place, absent mass conversion of everyone to orthodox, magisterial Catholicism as a precursor to political discussion. That seems rather unlikely, to put it mildly, so we are going to have to figure out how to do this in the ruins of what used to be Christendom. I believe that integralists really do have insights to contribute to this necessary conversation, but the thing they’re best at right now is making enemies on the Right, among people who naturally should be their allies.

Sohrab thinks complaining about this kind of thing is “tone policing,” but I strongly disagree. It matters how you address people who don’t agree with you, especially as a Christian public intellectual. Nobody is going to be mocked, sneered at, or shamed into adopting a reactionary Catholic triumphalist philosophy that turns non-Catholics into second-class citizens who have no say in who their leaders are. Sh*tposting is a good way to build a brand, but not a community that can convince other men and women of goodwill to join up, for the sake of restoring goodness and moral sanity in the real world.

Note to readers: I will be traveling for most of Thursday, and will not be able to approve comments. Please be patient.

UPDATE: A Catholic priest e-mails overnight:

How do we know that there is a ready-to-hand and authentic replacement for a liberal order that has descended into a left-wing ill-liberal order? Wouldn’t the centuries long run up to the descent mean that any authentic vision would find itself to be a small and marginalized minority? Wouldn’t it be historically and sociologically more likely that the strongest opposition would come from a right-wing ill-liberal order that was a type of mirror image of the left-wing?As I used to say in the 80s to orthodox seminarians who longed for the replacement of the liberals with “law and order” conservatives: “I’m too Irish to be for ‘law and order’ — I want to know whose law and whose order.” I called it trading the 70s for the 40s, and declared I wasn’t keen to live under either regime. Thing is, there’s no guarantee we’re going to like what comes next and there may as a matter of fact be no way at this point to avoid whatever it is.I think we should consider that the collapse of the liberal order in the West could prove long and ugly, with little influence coming from right believing folks for many, many years–if not generations.

I’m dumbfounded. Why would you or any Christian realist desire integralism, even in preference to a repressive regime? It is a mockery of Christianity which never has and, please God, will never exist in the real world. Indeed, from a realist or Christian perspective I fail to see how it actually realizable in our fallen world. Better to live for centuries of marginalization like Christians in the Roman Empire, in Ireland under British tyranny, and in Japan under their anti-Christian rulers, then to live thinking an earthly regime with it’s inherent corruptions–and it attendant corrupting influences on ecclesial leaders and institutions–is an incarnation of Christianity and the Kingdom.Beware, especially when faced with grim options for temporal governance, the implicit triumphalism and delusion of those “realists” or “Christians” who proclaim “we are aligned with truth and goodness, so we must dare to act creatively, to lead, to inspire, to rule.” Like Christ, any realist Christian has to recognize that service in charity and truth rather than ruling must be our constant goal. The road to Hell…

Your critique of the Catholic integralists was excellent. Theirs is a utopian position, undesirable in principle and thoroughly unrealistic in practice. And it ignores the Church’s own robust defense of religious liberty. A world state could only be despotic as Roger Scruton and Pierre Manent have often reiterated (and who wants a world state dominated by the progressive-liberationist-humanitarians around Papa Bergoglio!).Don’t expect a constructive dialogue. When one defends a conservative and Christian vision of democracy, they accuse the likes of you and me of being “right Liberals” who believe that liberty out to be neutral or indifferent regarding the human good and the truth of things. But you and I hardly believe that. Far from it! This rhetorical response is thoroughly dishonest. The alternatives available to us are hardly exhausted by integralism and a decayed relativistic liberalism. The refusal to acknowledge this palpable fact is truly mind boggling.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.