A View From Butovo Field

It’s been a whole year since I was in Russia, doing reporting for Live Not By Lies. Here’s a post I put up after my visit to the Butovo field memorial, in the far southern reaches of Moscow. It’s the national monument to those murdered by political violence. It encloses a field on which the secret police massacred 21,000 Soviet citizens in a 14-month period in the 1930s. From that post:

Standing at an exhibit at the edge of the field, looking at a tally of the number of dead killed each day, a Russian man struck up a conversation with us. He was there because his grandfather had been murdered by Stalin for telling people on the collective farm where he lived and worked to save their own houses in a fire, not the farm. Someone told the authorities, and that was the end of Vladimir Alexandrovich’s grandfather. On this spot they killed the priest of his church back then, and also the man who held the door at the church.

“And for what?” said Vladimir Alexandrovich, not expecting an answer.

Speaking to him in Russian, Matthew told him what my new book was about. When I told him that people are losing their jobs in the US over political issues, he said, “That’s a bad sign.”

“History always repeats, one way or another,” he said, heavily.

The main reason there is a national memorial here to the dead, and nearby a new church built to the memory of those martyred there, is the labor of Father Kirill Kaleda, a Russian Orthodox priest who lobbied the government for years to establish this permanent site of memory. From my talk with him in the kitchen next to the field:

But how to resist? We spoke of political combat. I don’t think Father Kirill had heard of The Benedict Option, but I told him about my frustration with American Christians who think the best and only way to fight these things is by electing politicians who will put the right judges onto the court.

He seemed to agree.

“The most correct way and the most productive way of battling has to be in your own world, that you can effect,” he said. “Not everybody can share their opinions with large number of people, but the way your living your own life, your insistence on having your own opinion, and more importantly the way you’re running your own family, this is more available to ordinary people. What did St. Seraphim of Sarov say: ‘Acquire the Holy Spirit and thousands around you will be saved.’ That is the best way. In fact, this path of podvig [a feat, a deed] is the one chosen by the faithful of the Russian Orthodox Church even in the middle of the most horrible persecutions.”

In the future, when Americans ask me what use the Benedict Option would be in a time of persecution, I will remind them of what the priest who serves a church named for the martyrs of the Bolsheviks said. He went on:

When thinking about this topic, it’s important not to be limited to just the canonized saints. What’s more significant is what in Russia we call the white headscarves — usually women, simple women with low education levels, who continued to go to church no matter what the conditions were. They were able to save something, and pass it on to their children. We can’t lose sight of these. There were so many of them.

One can be tempted to think that they performed no holy feats, that they just went to church. But in fact they were the ones that saved the faith and were able to preserve the church.

As he spoke, I looked behind his shoulder, through the window where snow was falling on a field where 21,000 men and women met their deaths, and were buried in a mass grave. It added weight and depth to the priest’s words.

Father Kirill continued to speak of the personal responsibility every Christian has for the space around him. He emphasized that believers can’t wait for great leaders to emerge to set things aright. Doing so is a way of avoiding responsibility for mastering the small spaces in which we ourselves live. “Out of these small spaces, that is what society is built of,” he said.

He spoke of a second-century saint who had a mystical vision:

He was shown the construction of a tower. When they were building tower in his vision, people brought stones. Some of them were perfect, and could put right into the construction. Others needed only a little bit of work. Others had to be thrown out. The angel who showed him this vision told him this tower is the church: a buillding that is being constructed throughout the course of human history. Each one of the stones is an individual member of the church. Those that spend their lives getting ready to be a part of the structure, they were able to be put right in by the builder. The history of the construction of this tower is the history of the construction of the church, and that is the history of humanity. The story of this construction is also the story of these people. The history of this tower is the history of these individual people — not of wars, not of church councils, not of a certain bishop occupying a certain position, that’s not what this tower is made of. So, the story of humanity is the story of individual people, not the story of presidents.

I told Father Kirill that the rise of identity politics seemed to me a worrying sign. The American left is training its people to regard others only in terms of their group identities, and to regard some groups as evil oppressors, and others as virtuous victims, simply by virtue of their group membership. How can we resist that? I asked.

“Here the most important thing is maintaining simple human contract, making sure that people have contact with each other,” said the priest. “This is made clear by the people who come here to Butuvo. They arrive with all kinds of opinions about what happened here, and about our country’s past. From their conversations, you can see a new relationship is being built, maybe even a brotherhood. It’s not that everybody changes their opinions, but the weight of what happened here begins to break down barriers. The most important thing is to see a humanity in others.”

Those words are why I re-posted part of this year-old entry today. Here are Father Kirill and me, after our interview:

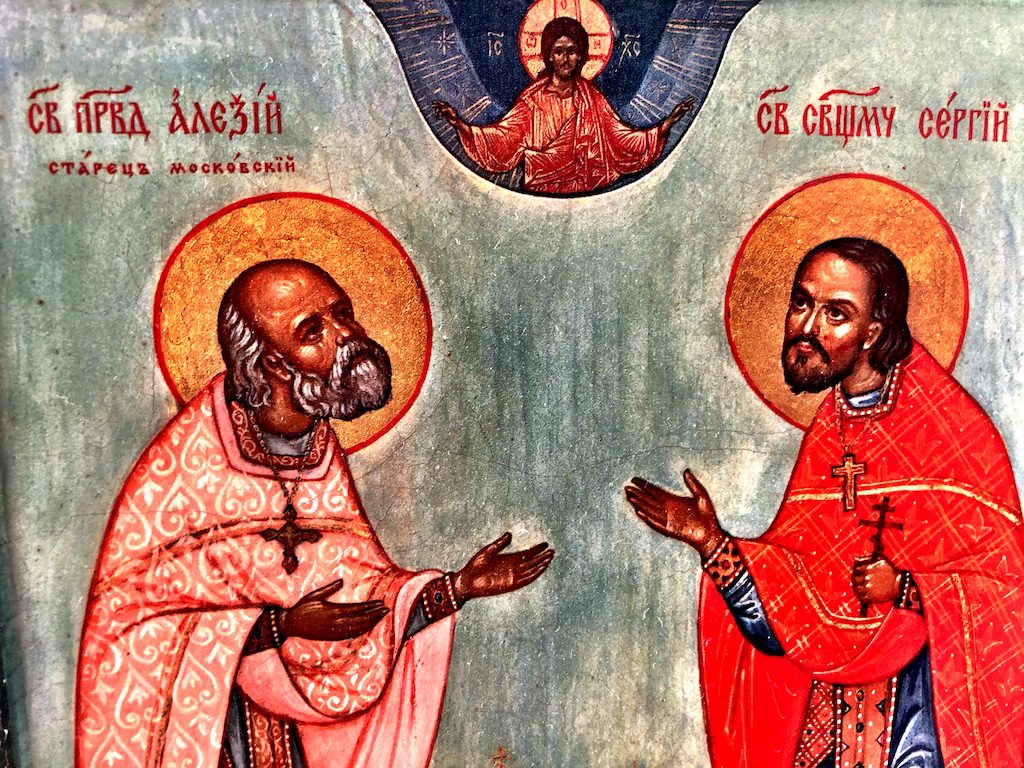

I want to add one more thing. At the top of this post you will see a detail from an icon image of St. Alexei Mechev, a Russian Orthodox priest who died of natural causes in 1923, and his son St. Sergey Mechev, also a priest, who was martyred in the gulag. I knew nothing about them until I met with Father Kirill, who said:

Every person in his life goes through some kind of test, through different kinds of difficulties. People that are accustomed to living in some kind of comfort, not only in a typical household way, but even in a spiritual way, then they are not able to bear these trials. The memory of a Russian saint who lived at the beginning of the 20th century, Father Alexei Michev comes to mind. Where did everything begin for him? He served in a small, poor church in the center of Moscow because of the fact of where their house was in this church, it was a raw, unheated space. His wife got tuberculosis and died, leaving him with a young son. In the Orthodox Church, you can’t marry a second time if you’re a priest, so he was in despair. He met with Father John of Kronstadt, now St. John of Kronstadt, who said to him, “What are you doing walking around grieving all the time? Look around you. Look at how much grief everyone around you has? Take that grief upon yourself, and when you take their grief upon yourself, you’ll feel that your grief is smaller. And he fulfilled the words of St. John.

Father Alexei Michev died in old age. His son Sergei was also an Orthodox priest — one who was martyred by the Bolsheviks. Here is their story from a Russian Orthodox website. Notice what it says about St. Sergei, whose name and story was unknown to me before Father Kirill brought it up:

Fr. Sergius entered the ranks of Russia’s New Martyrs for his uncompromising stand in ecclesial matters. His principal renown, however, rests upon his pastoral skills. The Maroseyka parish was unique in Moscow in cultivating an inwardly monastic orientation. Fr. Alexey often said that his task was to create “a monastery in the world,” by which he meant a parish family guided towards the same goal of sanctity and deification as the monastic.

Fr. Sergius held the same principle although later on he stopped speaking of it as a “monastery in the world,” because others had adopted this term as meaning some kind of community of secret monks or nuns who lived in the world while under obedience to monastic vows. Instead, Fr. Sergius took from ancient Russian church practice the term “repenting family.” He also referred to his parish as a “repenting-liturgical family.” It was very apt. As a spiritual director, he strove to cultivate in his flock a spirit of repentance and he encouraged frequent attendance at church services, which he considered to be the best school for the development of spiritual life.

My God. This martyr-priest, Father Sergei Michev, was living what I call the Benedict Option, and leading his parish that way. I will look for an icon of him today while I am in Moscow.

I asked Father Kirill what his message is for American churches. He said:

What happened in the 20th century in Russia serves as witness to the fact that many Russian people not only believed in God, but they also entrusted themselves to God. For them, the spiritual world and the kingdom of heaven were a reality. Despite the fact that for them, because of their own human weaknesses, it was a scary and painful time. Their podvig is the witness to the existence of another world, a spiritual world, and the Kingdom of Heaven. The lesson for us are the values of this earthly life, including our comfort, are nothing in comparison to the value of the Kingdom of Heaven. But this is a very difficult lesson.

What he meant was that it is not enough to say that we believe. We have to cultivate deep faith in the reality of God’s kingdom, and live it out. There is no other way.

As Matthew and I put on our coats to leave, Father Kirill called us into his office. There he showed us the mitre of St. Alexei. We both crossed ourselves and kissed this precious relic.

Russia! What a country.

Later, back in Moscow, my translator Matthew took me to the Maroseyka church, where both father and son had served. I prayed there, and bought an icon of the two in glory. It is now in my home. I have added them to the communion of saints whose prayers I ask. What a strange and wonderful thing. Only about a year ago, I did not know these men, but now, they are among my closest friends.

This is the kind of religious-themed post I might better have put on my new Substack daily newsletter, which I use for more religious and philosophical posts, ones less driven by the news. (Subscribe for free here.) But on a day fraught with anxiety over political violence, I thought it was important to highlight the words of a priest whose vocation it is to tend the garden of memory of those whose lives were taken for political reasons. There is a better way to live.