The Political Effects Of Cataclysm

As regular readers know, I’ve been studying the Russian Revolution as part of writing my forthcoming book Live Not By Lies. I had been struck by something I had never known about the revolution’s roots, until my reading last year: that a terrible famine in 1891-92 was a landmark in discrediting the Tsarist regime, and paving the way for revolutionary upheaval.

This bears pondering as the United States is at the early stages of what will almost certainly be a public health and economic crisis like none in our nation’s living memory.

In his terrific book A People’s Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891-1924, historian Orlando Figes explains why the great famine shook the imperial Russian system to its foundations. The state bureaucracy “was far too slow and clumsy, and the transport system proved unable to cope. Politically, its handling of the crisis was disastrous, giving rise to the general impression of official carelessness and callousness.”

The government’s mishandling of the crisis was manifest in many ways, but by far the error that most outraged the public was its export ban on grain, to make sure there was enough to feed the starving millions of peasants. It wasn’t the ban itself that was the problem, but the fact that the government telegraphed it a month in advance, which gave cereal merchants the opportunity to fulfill all their foreign contracts — leaving little for the hungry peasants. The tsar’s minister of finance opposed the ban entirely. Fair or not, the public came to see this policy as the main cause of the famine, Figes writes.

This was not unjustified. The government began by refusing to admit the famine’s existence. Figes:

The reactionary daily Moscow News had even warned that it would be an act of disloyalty [to use the word “famine”] since if would give rise to a “dangerous hubbub” from which only the revolutionaries could gain. Newspapers were forbidden to print reports on the “famine,” although many did in all but name. This was enough to convince the liberal public, shocked and concerned by the rumours of the crisis, that there was a government conspiracy to conceal the truth.

At last, the government admitted that it could not cope on its own with the crisis, and called on the public to form voluntary organizations to assist with famine relief.

Politically, this was to prove a . historic moment, for it opened the door to a powerful new wave of public activity and debate which the government could not control and which quickly turned from the philanthropic to the political. The “dangerous hubbub” that Moscow News had feared was growing louder and louder.

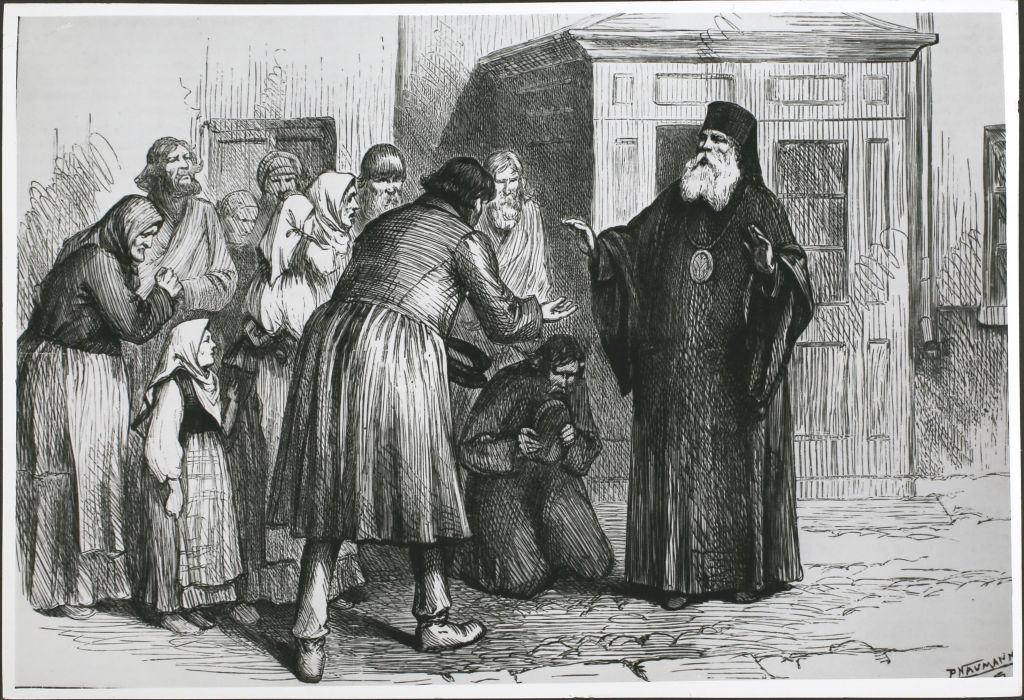

Figes writes that “the public response to the famine was tremendous.” People from all walks of society dropped everything they were doing, and jumped in to help the sick and starving. Some aristocrats (“Prince Lvov … threw himself into the relief campaign as if it was a matter of his won life and death”), progressive landowners, and bourgeois joined the relief campaigns. Anton Chekhov served as a cholera doctor to the famine-stricken, and went broke because he refused to be paid for his services. Tolstoy and his daughters “organized hundreds of canteens in the famine regions, while Sonya, his wife, raised money from abroad. ‘I cannot describe in simple words the utter destitution and suffering of these people,’ he wrote to her at the end of October 1891.”

A peasant who worked alongside Tolstoy in the relief campaign said the great man’s suffering was such that his beard went grey, he lost hair, and a great deal of weight. Figes again:

The guilt-ridden Count blamed the famine crisis on the social order, the Orthodox Church and the government. “Everything has happened because of our own sin,” he wrote to a friend in December. “We have cut ourselves off from our own brothers, and there is only one remedy — by repentance, by changing our lives, and by destroying the walls between us and the people.” Tolstoy broadened his condemnation of social inequality in his essay ‘The Kingdom of God’ (1892) and in the press. His message struck a deep chord in the moral conscience of the liberal public, plagued as they were by feelings of guilt on account of their privilege and alienation from the peasantry.

Keep in mind, readers, that the word “liberal” in this context does not mean what it means to contemporary American readers. “Liberal” here refers to those who wanted constitutional reforms to the monarchical system. They were to be distinguished from radicals, who wanted the overthrow of the system.

Figes:

For the guilt-ridden liberal public, serving “the people” through the relief campaign was a means of paying off their “debt” to them. And they now turned to Tolstoy as their moral leader and their champion against the sins of the old regime. His condemnation of the government turned him into a public hero, a man of integrity whose word could be trusted as the truth on a subject which the regime had tried so hard to conceal.

The historian notes that the Orthodox Church, which had recently excommunicated Tolstoy, forbade the starging peasants to accept food from his relief campaign.

Figes:

Russian society had been activated and politicized by the famine crisis, its social conscience had been stung, and the old bureaucratic system had been discredited. Public mistrust of the government did not diminish once the crisis had passed, but strengthened as the representatives of civil society continued to press for a greater role in the administration of the nation’s affairs.

The famine also reinvigorated the socialists and the radicals:

Marxism as a social science was fast becoming the national creed: it alone seemed to explain the causes of the famine. Universities and learned societies were swept along by the new intellectual fashion. … Petr Struve (1870-1944), who had previously thought of himself as a political liberal, found his Marxist passions stirred by the crisis: it “made much more of a Marxist out of me than the reading of Marx’s Capital.'”

Figes writes, “Even the young Lenin only became converted to the Marxist mainstream in the wake of the famine crisis.”

In short, the whole of society had been politicized and radicalized as a result of the famine crisis. The conflict between the population and the regime had been set in motion — and there was now no turning back. In the words of Lydia Dan, the famine had been a vital landmark in the history of the revolution because it had shown to the youth of her generation “that the Russian system was completely bankrupt. It felt as though Russia was on the brink of something.”

Now, what does this have to say to America in 2020, at the start of the coronavirus pandemic?

In the 1891-92 Russian famine, around 400,000 died (of a population of roughly 125 million). Nobody knows how many Americans will perish ultimately from this coronavirus epidemic, but the Washington Post reports:

Public health officials need to prepare for “disease burden roughly 10X severe flu season,” according to James Lawler, the director of international programs and innovation at the Global Center for Health Security and a professor for the University of Nebraska Medical Center, in a presentation given to the American Hospital Association and obtained by The Washington Post.

The CDC estimates that since 2010, between 12,000 and 60,000 people in the United States have died each flu season. Since the flu season began on Oct. 1 of last year, between 18,000 and 46,000 people have died among 32 million to 45 million illnesses, the CDC estimates.

In the worst-case scenario here, that would mean between 120,000 and 600,000 Americans would die. Out of a population of 331 million, that’s obviously a lower percentage. But it’s still a massive number, and they would meet their mortality in a nation that is much less inured to death than peasant Russia.

The mortality numbers are not the most important thing to think about politically. We have seen what happened, and is still happening, in China. Closer to home, culturally speaking, we see that the entire Italian province of Lombardy has been locked down in a quarantine attempt. As I wrote last night, the public health system in Lombardy, Italy’s richest province, is now on the brink of breakdown. Doctors there are openly talking about the prospect of triaging patients — in blunt terms, of allowing the elderly to die to reserve scarce medical resources for those more likely to survive. This is not peasant Russia; this is a modern advanced capitalist society.

Despite what our president says…

We have a perfectly coordinated and fine tuned plan at the White House for our attack on CoronaVirus. We moved VERY early to close borders to certain areas, which was a Godsend. V.P. is doing a great job. The Fake News Media is doing everything possible to make us look bad. Sad!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) March 8, 2020

… we are not prepared for what is hitting us now, and is about to sweep the nation. To be fair, and to be clear, no government could have prevented this virus from striking its shores. This is the reality of living in a globalized world. But as has been said many times, the US, and the world, had a month to prepare — February — after it became clear that this thing was going to go global. The Trump administration blew it. That month is not coming back.

This is not just Trump’s fault, though. This morning I spoke to the wife of a physician, who told me that her husband has been complaining that there is “no protocol” in place at his medical facility for handling coronavirus. She told me a couple of anecdotes that indicate they’re flying by the seat of their pants. A surgeon (not her husband) whose daughter is in home quarantine after having returned from Italy, is on site doing surgeries, not knowing whether this is right or not. My guess is that this confusion and lack of leadership is a lot more common around the US than we care to think. This morning on CBS’s Face The Nation, Dr. Scott Gottlieb, former FDA commissioner, said:

DR. GOTTLIEB: Well, we have an epidemic underway here in the United States. There’s a very large outbreak in Seattle. That’s the one we know about, probably one in Santa Clara or maybe other parts of the country, other cities. And so we’re past the point of containment. We have to implement broad mitigation strategies. The next two weeks are really going to change the complexion in this country. We’ll get through this, but it’s going to be a hard period. We’re looking at two months probably of difficulty. To give you a basis of comparison, two weeks ago, Italy had nine cases. Ninety-five percent of all their cases have been diagnosed in the last 10 days. For South Korea, 85 percent of all their cases have been diagnosed in the last 10 days. We’re entering that period right now of rapid acceleration. And the sooner we can implement tough mitigation steps in places we have outbreaks like Seattle, the- the lower the scope of the epidemic here.

MARGARET BRENNAN: Let’s talk about mitigation because when I asked Governor Inslee what he is doing and I asked him a few ways if he’d consider doing what Italy just did,–

DR. GOTTLIEB: Right.

MARGARET BRENNAN: –which is essentially trying to- I mean, they’re quarantining a quarter of their population in the most economically vital part of their country. This is a massive decision for them to have made. When I asked him about doing something like that in Washington state, he said, well, they’re talking about more distancing and–

DR. GOTTLIEB: Right.

MARGARET BRENNAN: — more measures like that. Is it just that it — governors like him don’t want to say out loud that we may have to do something like what Italy did?

DR. GOTTLIEB: Well, I think no state and no city wants to be the first to basically shut down their economy. But that’s what’s going to need to happen. States and cities are going to have to act in the interest of the national interest right now to prevent a broader epidemic.

Do you see the parallel with the Russian famine? The national government screwed up the initial response, which triggered action from local authorities, as well as civil society groups. Mind you, ours is a federal system, not an autocracy, so there is built into the system a separation of powers that makes national coordination more complex. Nevertheless, from a public perception point of view, the feds — in particular the Trump administration — has bungled the initial handling. Mind you, we still do not have widespread testing available … and the president continues to bumble-stumble and Potemkin-village his way through that embarrassing reality.

So as Dr. Gottlieb avers, it’s going to fall to state and local officials to take up leadership. Some will do well at this; others will do poorly. And private industry, and hospitals, will have to make these hard decisions, under very tight time constraints. They will be judged politically by how well they’ve done. Even though the president of universities and hospital systems (for example) do not have to stand for election, the impressions left on the public by how its public and private institutions performed in this crisis will either reaffirm faith in the current order, or dramatically undermine it.

Keep in mind too that America enters this crisis with a historical deficit of public trust in government and many other institutions of US life. We don’t have a lot of cushion. Do I even need to say anything about the economic impact this thing is going to have — and how that too will have a dramatic political effect? The fact that many of Russia’s wealthy were seen to be partying and enjoying the good life while so many peasants starved was not forgotten.

To wrap up: nobody can say for sure what is going to happen next. These next two weeks are likely to be when the real crisis begins here. Lombardy today may well be large parts of America over the coming fortnight. This black swan could easily cost Trump the presidency — read Douthat today about how, if Trump loses in November, it will be down to what he failed to do in February, with the pandemic coming toward us — but beyond that, it could lay the groundwork for a more sweeping and radical set of political and social changes. The imperial system remained in place in Russia after the famine, but within twenty years, the Romanovs had been murdered, and Bolshevik terror ruled the country, and eventually caused the deaths of exponentially more Russians than were lost in that famine.

Whatever happens with coronavirus, it will not be as severe as the Russian famine, nor will it be as serious as the 1918 flu pandemic, which did not bring down democracy. But it doesn’t have to be so deadly to have tremendous political effects, even if not revolutionary ones. We had better not underestimate this possibility. For example, today the conventional wisdom is that the Democratic Party is aligning itself behind the more moderate Joe Biden. But most of the delegates are yet to be decided, and if the country’s hospitals are overrun with pandemic patients in the weeks to come, Democratic primary voters may be far more likely to support Bernie Sanders, a candidate promoting more radical change, especially of the health care system.

Lydia Dan, quoted by Figes above, was 13 years old when the 1891-92 famine struck. Imagine the American Lydia Dans of our time: the kids and young adults who are about to live through this pandemic crisis, and its after effects. Do not imagine that they are not going to notice what this event reveals about the truths of the society in which they live.

UPDATE: And to put an absurdist cherry on top, the President of the United States tweeted this out today. He really did:

Who knows what this means, but it sounds good to me! https://t.co/rQVA4ER0PV

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) March 8, 2020

Who’s going to tell him?

UPDATE.2: Just now: