Sunday With St. Benedict

I returned a short time ago from an astonishing journey to Subiaco, to the monastery founded by St. Benedict, around the cave in which he lived as a hermit circa 500, praying and fasting and discerning God’s call. It was in this monastery that the saint wrote his Rule, and from which he founded the 13 monasteries under the Rule in his lifetime (he died in 547).

My Italian friends — a couple I know here in Rome, and their two children — took me to Subiaco today. It is about an hour’s drive from Rome, though when you get to the monastery, it feels like you have gone back in time, to somewhere very remote — which it was in the saint’s day. After going down to Rome from his birthplace in Norcia to finish his education, Benedict was so appalled by the decadence in the city — recall that the Western half of the Roman Empire officially collapsed in 476, just before Benedict’s birth, when the last Western emperor was deposed by the barbarians. Benedict left the city and went to live in a cave on the side of a mountain. He lived as a hermit for three years, praying and fasting and listening for the Lord’s voice to tell him what to do. In this time, he was fed by a monk named Romanus, who lowered food to him in a basket.

After he began his ministry, a monastic community grew up around his cave. Benedict lived in that monastery for 20 years. That’s where he wrote his Rule. The 12 monasteries he founded in the area around Rome, including the great one at Monte Cassino, where he and his sister St. Scholastica are buried, are daughter houses of this small monastic enclave clinging to the sheer side of a mountain. I love this statue of Benedict in a back courtyard of the monastery. It shows the saint with his hand outstretched to the mountain massing just feet away, with this message carved onto the pedestal: “Stop, cliff: do not harm my children.”

A close-up of his face:

I know the feeling, don’t you?

I could not capture the vertiginous vividness of the monastery’s location with my iPhone camera, but maybe these can give you a hint. Here is a shot of the terraced monastic gardens:

Another:

From the courtyard where the statue above is:

Notice the goats on the steps far below — this is rural Italy, after all!

The frescoes on the monastery walls mostly date from the 12th to the 14th centuries, but there is this incredible one of the Virgin Mary with the Christ child, and two unidentified saints, that was painted in the 8th century. Both the image and the painting style are Byzantine. Historians say this testifies to the fact that monks from the Eastern church (which, remember, was united to the West then) lived at this monastery. This fresco is in the “Shepherd’s Cave,” connected by a staircase to the part of the complex where Benedict’s cave is. Tradition has it that this is where Benedict first preached to the local shepherds who discovered him living in the hermitage:

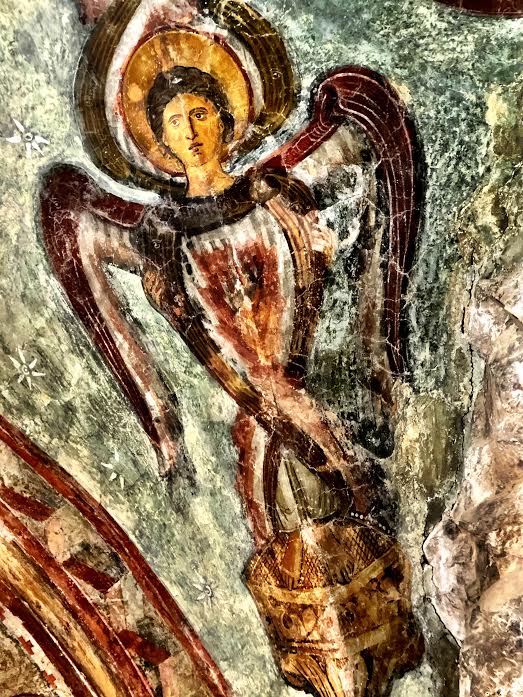

The frescoes are dazzling. Here are a couple of seraphim in one of the older chapels:

I don’t know who this saint is, but what’s most interesting to me is the graffiti, which create a palimpsest effect. The carvings are centuries old. Can you imagine that people from far into the past could not resist the urge to deface the holy image, simply to mark it with their names, as a sign that they had been there?

St. Francis of Assisi visited this monastery in 1223. This fresco image of him was almost certainly painted from life. It does not say “Saint,” nor does it feature him with a halo, or show his stigmata. In other words, this is probably what St. Francis looked like. Notice the eyes, with one bigger than the other, just like the famous 6th century Christ Pantocrator icon at St. Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai. In that icon, the left side (the viewer’s right) is interpreted at representing Christ’s humanity, and the right side his divinity. See this side by side comparison to see how different they are. The asymmetrical portrait of Francis here suggests that the fresco painter was drawing attention the same thing in the future saint (not, obviously, that he is divine, but that in him we can see an image of Christ).

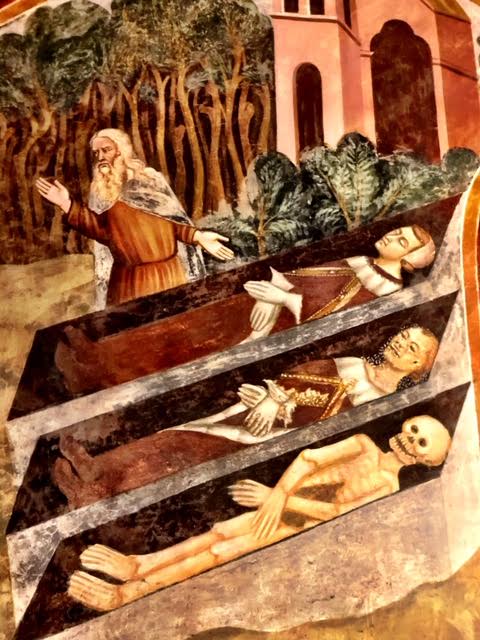

The medievals did not mess around with death. Here is St. Macarius the hermit, telling three carefreeyoung folks about what’s ahead:

The name of the monastery is “Sacre Speco” — Holy Cave — and here is the cave itself. There is a 17th century statue of young Benedict and the basket inside which his food came to him. You can’t really see the dimensions of the cave in this photo, and I wish the statues weren’t there. Still, it is hard to express the power of standing there in the cave where this simple Christian lived and prayed for three years, before he emerged to change the Western world forever:

If you know anything about St. Benedict, even if it’s just by reading The Benedict Option, you know that in many respects, the future of Western civilization was decided in that cave, in the dialogue between the young man Benedict and the Holy Spirit. Inside the stony earth, a symbol of the depleted spiritual energies of the dead Empire, a new spiritual seed gathered strength, and germinated. The Rule that Benedict wrote when he emerged from the cave, and the monasteries he founded, in turn grew quickly, spreading their vines across barbarian-ruled Europe. Thousands of men and women entered Benedictine orders in the early medieval period. They preached the Gospel, they converted peoples, they taught them how to pray, they instructed them on how to cultivate crops, and how to make things — knowledge that had been lost in Rome’s devastating collapse. And they began to teach children. Slowly, over the decades and centuries, the Benedictine monastics — foremost among Churchmen — laid the foundation for the rebirth of civilization in the West.

The rebirth began when Benedict of Nursia emerged from that cave in the early years of the 6th century, and brought to the world what he had been given in the darkness. It is fitting that Francis of Assisi, a spiritual revolutionary of the next era in the Western Church’s life, made pilgrimage to Benedict’s holy cave, and prayed there. Think of this passage from G.K. Chesterton’s life of St. Francis:

In a better sense than the antithesis commonly conveys, it is true to say that what St. Benedict had stored St. Francis scattered; but in the world of spiritual things what had been stored into the barns like grain was scattered over the world as seed. The servants of God who had been a besieged garrison became a marching army; the ways of the world were filled as with thunder with the trampling of their feet and far ahead of that ever swelling host went a man singing; as simply he had sung that morning in the winter woods, where he walked alone.

Chesterton’s lines are beautiful, but don’t get the idea that Benedict “stored,” in the sense that he hoarded. Rather, in the way of life he taught and embodied in his monks, Benedict stored spiritual knowledge and deepened practices that allowed Christian to inhabit those truths in a disciplined way. Francis was more literally evangelical than Benedict; that was his calling and his charism. But Francis received what his predecessor in the faith had done as much or more than anybody to preserve for him.

Today, in the life of Western Christianity, and of Christianity the world over, we desperately need greater attention to storing. I am reminded of this passage from The Benedict Option, in which Marco Sermarini reflects on the troubles of this world, and what good men and women are called to do:

He shrugged. “I don’t know what’s going to happen next, but in the meantime, we have to fight for the good,” he said. “The possibility of saving the good things in the world is only this: a possibility. We have to take the chances we have to set a rock and to keep this rock steady.”

We walked back to the jeep, climbed in, and drove on.“Nothing we make here will be eternal, but we have to build them as if they will be eternal,” Marco continued. “That’s what God wants. If you promise yourself to a woman for a lifetime, that is a way of making the eternal present here in time.”

We have to go forward in confidence that the little things we do might, in time, grow into mighty works, he said. It is all up to God. All we can do is our very best to serve Him.

Sometimes Marco lies in bed at night, worrying that his efforts, and the efforts of his little Christian community, won’t amount to much in the face of so much opposition. He is anxious that the current will be too strong to resist and will carry them over the falls as well.

“I know from the olive trees that some years we will have a big harvest, and other years we will take few,” he said. “The monks, when they brought agriculture to this place, they taught our ancestors that there are times when we have to save seed. That’s why I think we have to walk on this road of Saint Benedict, in this Benedict Option. This is a season for saving the seed. If we don’t save the seed now, we won’t have a harvest in the years to come.”

Though it is perched on the lip of a cliff, almost hovering over a gorge with an unseen river rushing by, the Sacre Speco monastery is a place of almost overwhelming peace. Petrarch, who visited it, called the monastery the “threshold of Paradise,” and it’s not hard to see why. It really is one of those liminal, “thin” places, where spiritual realities seem closer than in the everyday. It is also a sign of hope: a reminder that if we abandon ourselves entirely to divine grace, a world-changing power can emerge from the humblest places. From a modest town in a forgotten outpost of the Roman Empire. From a mountainside hole high above a deep furrow in the wild forest. You never know. But you may hope.

Go to Subiaco, if you can. It is a great, great treasure. Every time I come to Italy, and every time I come to Europe, I find myself filled to bursting with gratitude for what has been preserved here for us all. We have to teach ourselves to cherish it, and protect it, and pass it on to future generations.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.