A Hard Look At Catholicism’s Crisis

Back in the early 2000s, when the Catholic sex abuse crisis broke open, the fact that the Internet existed made all the difference. The establishment Catholic media was largely useless in writing about the crisis, and the mainstream media, though vastly better, still had blind spots. At the time, though, blogging was a new thing, and individual Catholic bloggers aggregated stories and provided analysis that establishment media — both in the church and in the secular mainstream — could not or would not provide.

But there was a problem — an understandable one, given human nature, but still a problem. People within factions tended to only want to read reporting and commentary that reinforced their preferred narratives. Generally speaking, you could not find reporting and commentary on the Catholic left that breathed a word about the role that gay networks played within clerical circles, re: the scandal. It was hard on the Catholic right to find writers willing to confront problems with conservatives’ favorite narratives. For example, you were treading on dangerous territory if, as a Catholic conservative, you raised questions about the role that clerical celibacy may have played in creating a culture of sexual corruption.

Understand my point here: I’m saying that you couldn’t even raise the questions, because the discourse police on your own side would set on you. This played out in other ways. After I lost my ability to believe as a Catholic, as the result of staring too long into the abyss of Church corruption, some of the same people who used to cheer me on when I wrote about church corruption as a Catholic were now quick to denounce me and to deny that anything further I had to write about it had any merit whatsoever. Again, I get that: it’s human nature.

Even at this late date, that kind of thing continues. Many Catholics can’t stand the radically orthodox Catholic website Church Militant, because they consider it to be too quick to credit rumors and conspiracies, and perhaps too vulgar in their reporting and commentary. Maybe these critics are right, at least to some extent. I honestly couldn’t say, because I no longer follow Catholic stories as much as I once did. But I do know this: sites like Church Militant arise because there are still big problems in the Catholic Church, ones that the mainstream media prefer not to cover, for whatever reason, and that the institutional leaders (e.g., bishops, heads of religious orders) will not address.

This morning on Church Militant, Christine Niles reports on how the Bishop of Fresno has quietly reinstated a priest who had been found with gay porn years ago, and who as recently as 2018 had been found with evidence that he was a sexually active gay man. Where else are you going to read stories like this, which bear witness to the corruption within the institutional church, and warn faithful Catholics about what’s really going on?

There are some rad trad Catholic sites whose writers, fourteen years after I left the Catholic Church, still rant about me and discount the things I say because I’m an ex-Catholic. They don’t get that I’m not their enemy. In fact, two years ago, even Benedict XVI’s private secretary praised The Benedict Option as a good guide for Catholics through the dark wood of the present moment. I see my public role now as one who tries to build bridges among Catholics, Protestants, and Orthodox, to make it feasible for us to defend each other against the threat of ascendant anti-Christianity. In my new book Live Not By Lies, I interview and quote from Catholics, Protestants, and Orthodox about their experiences of communist persecution. As people like the Catholic Silvester Krcmery, the Orthodox priest George Calciu, and the Lutheran pastor Richard Wurmbrand all testified, they found real brotherhood among Christians of all confessions who had been, like them, thrown into prison for their faith.

The persecutors will not distinguish between Catholics, Protestants, and Orthodox; they will come after us because we profess Christ. This does not make the real and serious theological differences among our confessions go away, but it does put them into context.

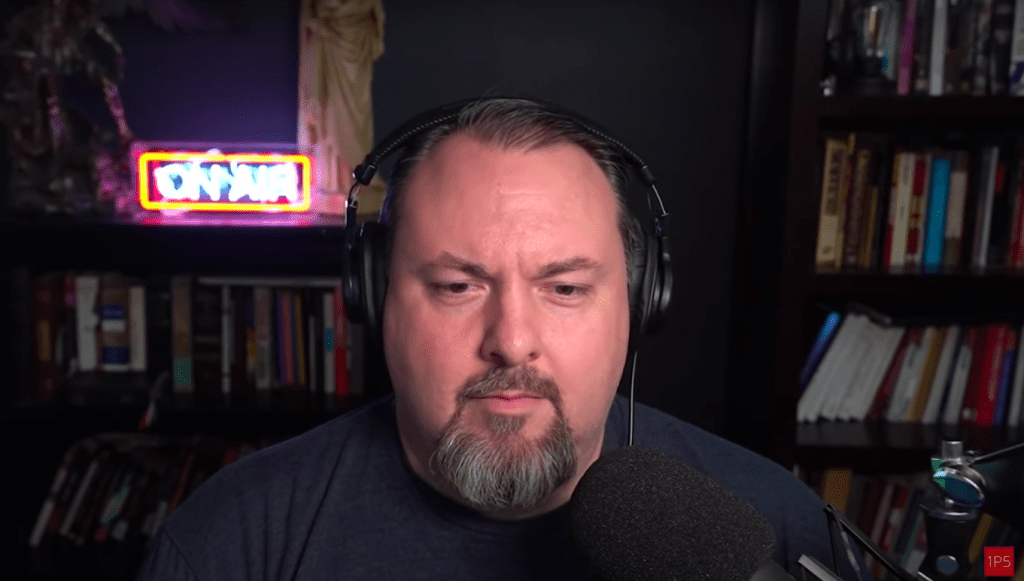

I have been an infrequent reader of the traditionalist Catholic writer Steve Skojec for a while. One thing that draws me to Steve is that he really does seem like a man who is urgently trying to get at the truth. He sees that the line between truth and lies does not run between trads and liberals within the Catholic Church, but down the middle of every Catholic heart. (This is true for all of us, of course.) In his most recent piece, he sends up a cri de coeur against people on his own side whose ideological priors keep them from diagnosing the deepest crises in the Catholic Church, and working out a prescription. He begins by quoting his wife, who some time ago asked him why he kept fighting Church battles when it made him so miserable. Skojec writes:

The truth was, I didn’t have an answer for her at first. In fact, it took me a few days before I thought I knew. I came back to her, and I did my best to explain it:

“I think,” I said, “It’s because my Catholicism is my entire identity. It’s all I’ve ever known, or been known for. I’ve been actively involved in the Church and defending the faith since I was a kid. And if the people in charge of the Church right now are right, if their side wins, it means it was all for nothing. It means the Church is a lie. And if that’s the case, I don’t even know who I am anymore.”

“Really,” I concluded, “I’m not just fighting for the Church. I’m fighting for my own survival.”

This is a question that has haunted and plagued me ever since: what if they are right? What if I’ve spent my whole life defending something that isn’t even real? Something totally changeable, and not timeless in its truth?

There are times when it really gets to me. There are others when old habits take over, and swatting down heterodoxy and promoting the true faith are as effortless and familiar as riding a bike.

But more and more lately, I’m feeling very restless. The question comes back to bother me more than I’d like to admit. I don’t like feeling guilty about asking questions I’m being forced to consider, as though that makes me the bad Catholic, and not the people doing this stuff. The surreality of the events of 2020 have only seemed to warp the fabric of what is known even more. There’s a profound sense, as my friend Kale Zelden wrote recently, that things are very broken, and that we desperately need to figure out how to make sense of the world again.

Skojec writes about how he started watching Jordan Peterson videos, and he was dazzled by how Peterson grappled with big ideas without a sense of tentativeness. Peterson, he said, was unafraid — and that was liberating:

And then the mirror flipped, and I realized that I have never felt so free. That even though I started 1P5 so that I could say the things that needed to be said that were considered taboo, I am nevertheless still trapped within that adamantine framework of the Church. Consequently, whenever I write about a difficult topic, or fire off a tweet, or speak into a microphone for a podcast, I can count on an army of amateur theology-checkers and censors to ferret out my mistakes (of which there are no doubt many) like some Monty Python-esque version of the online inquisition, looking to correct or prove me wrong, or perhaps even to humiliate me in articles and posts without ever addressing me at all — me, the person, the fellow brother in Christ — all because I colored outside the lines.

I cannot overstate how inhibiting that awareness is to authentic curiosity, or problem solving. I can’t tell you how much it feels like a cage, when all you want to do is hash things out, deconstruct the concepts, get your hands dirty, and figure out what makes it all tick.

The freedom to make mistakes, to sincerely get things wrong, and to keep digging is what we need right now. More than ever. We don’t need our intellectual hands and feet to be tied, or to get zapped with a cattle prod every time we step out of bounds. Because what we’re dealing with is way too important to simply gloss over. In a way, we need to do what Pope Francis says, and make a bit of a mess.

What do we do when time and again, we are confronted with the unthinkable? What happens when the pope himself — THE POPE HIMSELF — says contraception is OK, or approves Holy Communion for people living in adultery, or changes the Catechism in a way that reverses the Church’s infallible bi-millenial teaching on the moral liceity of the death penalty (in a way that opens the door to reversing everything else), or signs an interfaith document that undermines the exclusivity of salvation through the Church? What do we think when we hear again and again through one of the pope’s most trusted confidants that he thinks hell doesn’t actually exist, and that the souls of the unrighteous are merely annihilated? What about when he says the miracle of the feeding of the 5,000 wasn’t really a miracle – wasn’t “magic” – but just some act of sharing? What about when he says of the Blessed Mother that she wanted to accuse God of lying to her? Or that Jesus actually “became sin“? What of a hundred or a thousand other troubling things?

Skojec emphasizes that he is not a sedevacantist, nor does he advocate leaving the Catholic Church. But he said that the faithful cannot strengthen themselves with “platitudes,” or by refusing to see the Church for what it is today. He says a priest even told him once to stop thinking about all this. That, says Skojec, is the coward’s way out. More:

Those of my generation have never seen a Church not at war with herself. Never known a Church where there were not two competing sets of doctrines, two fundamentally incompatible liturgies in her central rite, two entirely different sets of sacraments, two completely disparate versions of a thing we’re told is characterized by unity, of all things, as one its four distinguishing marks.

No amount of preference for one way of doing things or another is going to make the dichotomy go away. No amount of fence-straddling the pre and post-conciliar worlds will make either one feel like it’s really part of the same religion. No amount of wishcasting will make the hermeneutic of continuity believable. I have spent approximately half of my life on each side of the fence, and although I can tell you which one I think is better for the life of the soul, neither is without significant limitations and drawbacks.

But they are certainly not equal, and the Church throws all her weight behind the inferior things. It’s as if she wants us to lose our faith.

So now, as the Church faces inevitable post-covid demographic collapse, those of us who are left on either side of this artificial and carefully-designed divide need to find a way to work together. We will be, before long, all that is left.

And we need to find a way to answer, or at least live with, the questions that my litany of observations above prompt in our minds with utmost urgency.

We are obligated, I think, to ask hard questions. Questions, even, that we’ve been told that we are not allowed to ask.

There’s so very much more in this piece — and it’s not just for Catholics. I stay out of the Very Online Orthodox world, because I remember all too well how getting caught up in that world as a Catholic broke me. Not long into my life as an Orthodox Christian, I involved myself in the Orthodox version of same, and met a bad end. For the sake of my own faith, I resolved to stay out of the online Orthosphere, not because I don’t think the questions Very Online Orthodox talk about are unimportant — sometimes they are, but often they’re serious questions — but because I know my own faults all too well, and don’t want to get mixed up in that again. I recognize clearly the kind of online Christians that Skojec is talking about, and how their instinct to police discussion like penny-ante inquisitors makes it impossible for men and women of good will to have the urgent conversations that they need to have for the sake of the survival of the faith. To get drawn into fruitless, rancorous debates with them is to risk being disheartened about the possibility of Christian resistance.

We Christians are in the beginning stages of a Long Emergency, to borrow a James Howard Kunstler term. When I was in Moscow last fall, interviewing an older Russian Baptist pastor about resistance to communism, I didn’t stop to think about where he stood vis-à-vis the Russian Orthodox Church. I just thought, “Here is a believer with whom I deeply disagree on some things, but who comes from a community that suffered intense persecution. What can I learn from this brother in Christ?” Here is some of what he told me:

Two days later, I sat in a café in the heart of Moscow listening to Yuri Sipko, a retired Baptist pastor. In his village classroom in the 1950s in Siberia, Sipko and his classmates were given a badge with a portrait of Lenin. At age eleven, the children were given the red scarf of the Young Pioneers, a kind of Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts for communist youth. Teachers drilled the children in the slogan of the Pioneers: “Be ready. Always be ready.”

“I didn’t wear the pin with Lenin’s face, nor did I wear the red scarf. I was a Baptist. I wasn’t going to do that,” recalls Sipko. “I was the only one in my class. They went after my teachers. They wanted to know what they were doing wrong that they had a boy in their class who wasn’t a Pioneer. They pressured the director of the school too. They were forced to pressure me to save themselves.”

To be a Baptist in Soviet Russia was to know that you were a permanent outsider. They endured it because they knew that truth was embodied in Jesus Christ, and that to live apart from him would mean living a lie. For the Baptists, to compromise with lies for the sake of a peaceful life is to bend at the knee to death.

“When I think about the past, and how our brothers were sent to prison and never returned, I’m sure that this is the kind of certainty they had,” says the old pastor. “They lost any kind of status. They were mocked and ridiculed in society. Sometimes they even lost their children. Just because they were Baptists, the state was willing to take away their kids and send them to orphanages. These believers were unable to find jobs. Their children were not able to enter universities. And still, they believed.”

The hour is too late for us to argue over the orthodoxy of Russian Baptists. Am I indifferent to the theological differences between us? No. I think Pastor Sipko is wrong about some important things — and I pray that one day, we will be in a civilizational situation in which Baptists and Orthodox have the luxury of disputing each other at length. Now is not that time, though. As Skojec says about Catholics, I say of all small-o orthodox Christians: We will be, before long, all that is left. We need to find a way to work together.

This is the kind of realist ecumenism I advocate in The Benedict Option, and one that I urgently advocate in Live Not By Lies. One of these days, we or our descendants are going to get to know each other, and to depend on each other, in prison, so we had better start building those bridges of faith and solidarity now. Trust me, people: you are better served by building relationships with Christians of other confessions who see clearly what’s happening now, and are not afraid to say so, than you are by being intimidated by those within your own church who are too scared to ask the hard questions, and who try to defend their own fear by shutting down those who do ask.

I have never met Steve Skojec, but that man, a true-believing Catholic trad, is my ally — and I am his. We cannot afford not to stand side by side against an enemy like this. Skojec titles his essay “No More Platitudes: It’s Time To Take A Hard Look At The Crisis Of Catholicism.” Change the word “Catholicism” in that title to “Christianity,” and that headline is a sentiment I agree with one hundred percent.