Robert E. Lee, Wendell Berry, & Uncle Charlie

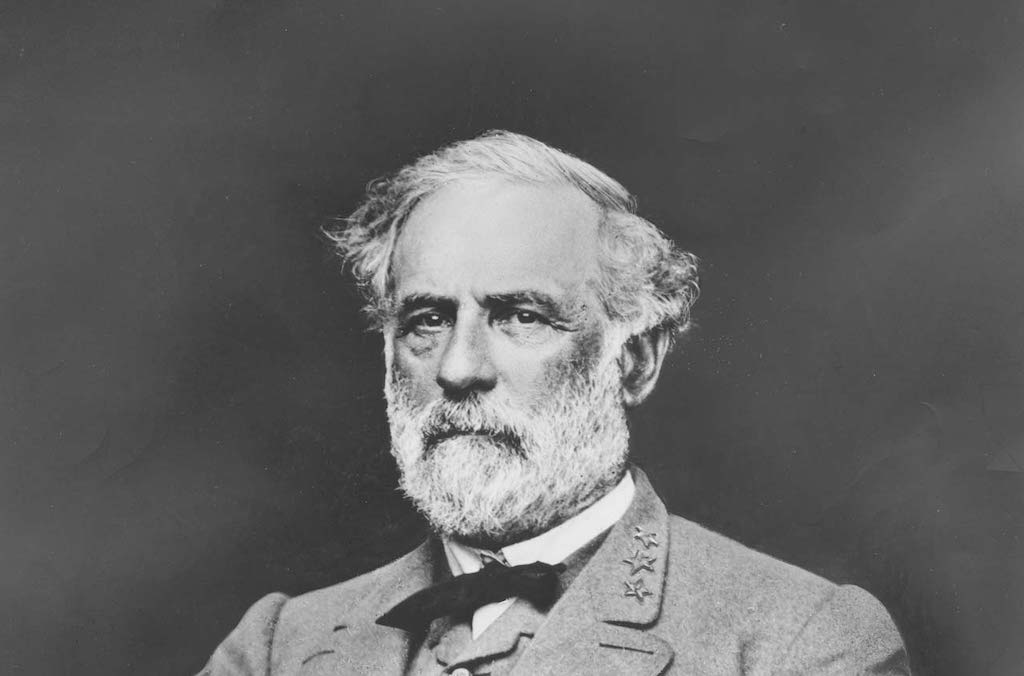

Reader Rob G. passes along this short piece by the Baptist theologian Russell Moore, supporting the removal of Richmond’s Robert E. Lee statue. In it, Moore recalls years ago, as a seminary professor, trying to decide whether it was right to remove a portrait of Lee after a black seminarian winced upon seeing it. Moore counseled removing it, but then went out to see Wendell Berry to see what he would say. Excerpt:

Around the time that I had sent my response to the student, I was out at the poet and novelist’s farm, where at his kitchen table I awkwardly brought up the subject of Lee. I say “awkwardly” because I was quite sure that Berry would disagree with my counsel. After all, I had just read a defense he’d made of Lee, and I was sure he would think that the picture’s removal was one more example of a mobilized and rootless modern society that refused to even remember the past.

Other than the one essay, however, I really had no reason to guess his response. Berry, after all, is an agrarian writer but decidedly not in the strain of “moonlight and magnolias” Southern agrarianism, which at best whitewashes and at worst romanticizes the violent white supremacist caste system of old Dixie. To the contrary, he has written poignantly on the “hidden wound” of white supremacy and the damage it has done.

Still, I found the author’s 1970s-era essay on Lee inconsistent. He portrayed the general as an exemplar of someone facing the choice between principle and community, when he resigned his commission in the United States Army to join the Confederate cause. To Berry, Lee’s motivation was not a defense of slavery but rather a refusal to go to war against his relatives and his home of Virginia. The author concluded the General was right.

“As a highly principled man,” Berry wrote of Lee, “he could not bring himself to renounce the very ground of his principles. And devoted to that ground as he was, he held in himself much of his region’s hope of the renewal of principle. His seems to me to have been an exemplary American choice, one that placed the precise Jeffersonian vision of a rooted devotion to community and homeland above the abstract ’feeling of loyalty and duty of an American citizen.’”

Berry was right, it seems to me, that morality is grounded best in what he would call “membership” rather than in abstractions. Where he was wrong, though, was in seeing the boundaries of that membership. The precise evil that Lee fought to maintain was a community in which some people were seen as members and others were seen as property to be exploited and tortured.

Berry told Moore that removing the portrait was the right thing to do. Read it all.

Rob G. comments:

Moore makes some good points here, and on one level I agree with him. But I think he fails to grasp the bigger picture, which is that this whole thing is not just about the statues. His error is that he considers the thing in isolation, which, given the social, cultural, and political issues involved, is at very least shortsighted, and at worst an exercise in do-good and feel-goodism.

I tend to agree with Rob here, and in fact Rob’s comment helps me understand why I agree with Moore in principle, but can’t endorse his column. I wanted to read the entire Berry essay where he discusses Lee, but couldn’t find it online. I did find the Lee excerpt from the essay on Google Books. I couldn’t cut and paste, but I did take some screenshots. Here’s the Lee passage:

Berry, who has written movingly on the “hidden wound” of American racism, might have changed his mind on Lee since he penned those words. Still, I find them persuasive. As Berry makes clear, the tragedy of Robert E. Lee was that no matter which choice he made, there would have been pain. For Lee to have remained loyal to the Union would not have entailed mere disagreement with his family and his people; it would have required him to make war on them.

This is something I don’t think we fully consider today — that is, what it means to make war (a real shooting war) on your own family. Could you do it today, to remain loyal to the government in Washington? Even though we are far more connected and aware today, thanks to technology, than the Americans of the 1860s were, it is still a hell of a thing to ask people to take up arms against their own friends and family to be loyal to a distant abstraction.

Would you turn your abilities against your own people? Even if those people believed wrong things? Even if they believed wicked things? I could conceive of a circumstance under which I could do that, but it would be extreme. I would like to think that I would have fought against the slave state of the Confederacy, but I think it would have been so very difficult for a Southerner in 1861 to have turned his back on everything and everyone he had ever known to take up arms against them, even if he believed their cause was unjust.

When I look at a statue of Robert E. Lee, I see a tragic figure: a great man who fought for the wrong side, but did so out of noble motives, and who suffered a deserved defeat — but bore it with dignity, and worked for the reconciliation of the Union. He symbolizes the best of the South — or the white South, at least. I think we can and should look back on him with magnanimity. I understand that good people can disagree on that. But if you are so very sure that Lee deserves no monument, and no sympathy, ask yourself: if there were another war, would you take up arms against your own people, even if they were wrong? If the answer is yes, do you not at least understand the immensity of that tragedy?

I think this contemporary controversy has little to do with the actual Robert E. Lee, and a lot to do with Lee as a symbol of a certain kind of person that America’s ruling class has decided is deplorable, and must be crushed. I don’t believe it’s about justice; I believe it’s about power. And it’s about the victory of a certain kind of radical mindset.

Let us create a figure we will call Uncle Charlie. Every Southerner has an Uncle Charlie in his family, or at least in his family’s circle (Uncle Charlie might be a neighbor). Uncle Charlie is an old white man, and he is a racist. Charlie usually keeps his mouth shut about his racial opinions at family gatherings, but when he’s been drinking beer, he’ll tell a racist joke, or make a comment that ticks everybody off. Maybe Aunt Joanie will say something to him about his big mouth, but more often than not, everybody just rolls their eyes at each other and stays quiet, because it’s easier to tolerate Uncle Charlie’s mouth than to start a big fight over it.

As mad as you can get at Uncle Charlie, you also know that Uncle Charlie is a complicated person. He lost his job when the mill closed twenty years ago, and was never able to get good work again. He was humiliated by his unemployment, and it made him hard, and bitter. His son, your cousin Bobby, died of a drug overdose, and his other son, Dickie — nobody knows what happened to him, but Charlie and Joanie only ever hear from him when he needs money. They don’t have much money, but they can’t stand to think of their flesh and blood suffering, so they usually scrape something together to give to him. You know that this shames Charlie too, because he got drunk last Thanksgiving and talked about how much it hurts him that Dickie don’t care nothin’ for him but that he gives Dickie money.

You also know that when that black family down the road from Charlie and Joanie lost their house in a fire, Charlie and Joanie were the ones who organized the relief effort with the local churches. You remember that time at the family Christmas get-together when you thanked Charlie for doing that, and then pointed out that you didn’t understand how he could be so compassionate to his black neighbors, but still hold on to his racist beliefs. Charlie just looked at you like you were speaking Greek. He literally did not understand the point you were making. And you didn’t understand why he didn’t understand. Later, when you were back home in New York, you tried to explain Uncle Charlie to your friends at the bar, but nobody could figure him out either.

Uncle Charlie taught you and your brothers and sisters how to ride horses. He and Joanie had horses for a while. He also listened to you when you were being bullied at school, and your own parents didn’t have time to hear you out. Charlie did, and he went up to the school to talk to the principal on your behalf. You loved him for that. And as ornery an old cuss as he is, you know that if you got in trouble, Charlie would get in his truck and come to wherever you are to help you out. You might have to listen to his redneck stories all the way home, and put up with his crackpot political commentary, but the point is, Charlie would do anything to help you, because though he thinks you’re a n–ger-loving crazy liberal who got ruined in college, you’re still family.

I’m telling you, nearly every Southern family has an Uncle Charlie. Maybe nearly every family does, period. If the day should come when you and I should feel compelled to take up arms against Uncle Charlie, well, that will be a terrible day. Uncle Charlie cannot be reduced to his ugly opinions about non-white people. Anybody who tells you that you have to prove your own decency by your willingness to denounce Uncle Charlie and treat him like the enemy is, in fact, your real enemy.

That’s what all this feels like to me: it’s not enough for the successors to the Yankees to have won, but they also demand that we all denounce Uncle Charlie, and damn the things that are precious to him. I’m not loyal to the Confederacy (which, as I’ve said a million times, deserved to lose). I am loyal to Uncle Charlie, and to the memory of my ancestors who fought in that war. Abraham Lincoln and the victorious powers were wise in that they made it possible for the South to bear its defeat with relative dignity. The victors realized that the war they fought to preserve the Union could have been won on the battlefield but lost if Southerners had contempt for the Union. Fifty years later, the lack of this kind of wisdom led to the Versailles Treaty, which exacted harsh punishment on Germany, and paved the way for the rise of Hitler.

It is unwise to put people in the position where they believe they have to hate their own family to prove that they are good and worthy of respect. Similarly, it is unwise to put people in the position where they believe they have to violate their own consciences in order to prove to their family that they are worthy of respect. A good society is one that can live with these tensions.

I hold a view that almost nobody does, as far as I can tell. In 2020, there was a Black Lives Matter march in my hometown, St. Francisville. There was also a petition, started by my niece Hannah Leming, calling on the Historical Society to change the annual Audubon Pilgrimage, a festival dedicated to highlighting the Old South plantations around there. Hannah’s petition called on the Historical Society either to expand its scope to include frank discussion of slave life, or to abandon it. After all, nearly half the people who live in West Feliciana Parish are black — and they’ve been excluded from this festival all their lives. Why would they want to be part of a festival that celebrates a culture that enslaved their ancestors.

I wrote about that here. I wrote in support of my niece’s petition. I did not want the Pilgrimage to end, because I think it is important to observe the past and honor what is honorable in it. I hoped the Pilgrimage would simply expand to tell the whole story, not just the moonlight-and-magnolias narrative. The Historical Society ended the Pilgrimage — too quickly, I thought, but I later came to see that it’s simply not possible in this cultural environment to have something like what I envisioned. At the time, there was talk about tearing down the Confederate statue outside the town courthouse. I oppose that. The statue has stood for a very long time, and I think it would be damaging to take it down. What I would like to see instead is a statue built on that same courthouse square to the Rev. Joseph Carter, a brave black pastor who stood down a white mob on the courthouse lawn to register to vote in the 1960s (hear more about that here). Rev. Carter’s courage tells a next chapter in the story connected to that Confederate soldier. He represents the conquering of the social order that the soldier defended — a conquering that came one century later, after more struggle and bloodshed.

Why can’t we tell both stories in statuary — not because the Confederate soldier is morally the equal of Rev. Carter, but because both of them were men of this place, caught up in history, and struggling with loyalty to principle and to people (because the Rev. Carter brought trouble onto his family from racist whites, it could be said that by standing up for his right to vote, he put his family in danger).

In other words, I want more history, not less of it. When I walk through Paris, I loathe the evil that the French revolution’s leaders wrought … but I would not support removing their statues, or their names from public places. They too were Frenchmen. Obviously there has to be a limit to this. I wouldn’t support keeping statues of Hitler or Lenin up, nor would I favor allowing places to be named after Stalin or Mao. But the evil of those figures was so extreme as to be beyond normal categories. When it is possible, I favor more history, not less. In my hometown, the Confederate soldier tells us who we were, and therefore, part of who we are. A statue of Rev. Joseph Carter, same thing. We need to build that statue. I never met the man, but I honor his memory, I recognize him as a brother in Christ, and I thank him for what he did not just for the black people of our parish, but for all of us.

Anyway, back to Lee: would you be able and willing to turn your talents against your people, to the point of taking up arms against them, and killing them for the sake of principle? If so, would that decision be easy for you? If you wouldn’t do it, or if it would be a hard decision to make, maybe then you should spare a little sympathy for Robert E. Lee, and pray that neither you nor any other American will ever have to make a similar tragic decision.

UPDATE: I’m writing my Substack newsletter for later today, and I just ran across something in my notes from the psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist’s great book The Master And His Emissary, about the divided brain. This seems relevant here:

The left hemisphere is always engaged in a purpose: it always has an end in view, and downgrades whatever has no instrumental purpose in sight. The right hemisphere, by contrast, has no designs on anything. It is vigilant for whatever is, without preconceptions, without a predefined purpose. The right hemisphere has a relationship of concern or care (what Heidegger calls Sorge) with whatever happens to be.If one had to encapsulate the principal differences in the experience mediated by the two hemispheres, their two modes of being, one could put it like this. The world of the left hemisphere, dependent on denotative language and abstraction, yields clarity and power to manipulate things that are known, fixed, static, isolated, decontextualised, explicit, disembodied, general in nature, but ultimately lifeless. The right hemisphere, by contrast, yields a world of individual, changing, evolving, interconnected, implicit, incarnate, living beings within the context of the lived world, but in the nature of things never fully graspable, always imperfectly known–and to this world it exists in a relationship of care [Emphasis mine — RD]. The knowledge that is mediated by the left hemisphere is knowledge within a closed system. It has the advantage of perfection, but such perfection is bought ultimately at the price of emptiness, of self-reference. It can mediate knowledge only in terms of a mechanical rearrangement of other things already known. It can never really ‘break out’ to know anything new, because its knowledge is of its own representations only. Where the thing itself is ‘present’ to the right hemisphere, it is only ‘re-presented’ by the left hemisphere, now become an idea of a thing. Where the right hemisphere is conscious of the Other, whatever it may be, the left hemisphere’s consciousness is of itself.

I think this may be a very old cultural difference.

David Fisher Hackett, in Albion’s Seed, mentioned a study of colonial-era wills analyzed for regional differences, which found that Pennsylvania Quaker testators (I had to look that word up: it means a person who makes a will) occasionally disinherited one of their children for leaving the Quaker faith, but Southern testators never, ever did that. Hackett mentioned it to illustrate the high value placed on family loyalty in the South as compared with Pennsylvania then.

This country’s college town culture is descended from colonial Quaker culture. Of the four main English-speaking cultural groups who colonized this continent, only the Quakers believed in education for everybody, so they (and therefore their values) came to dominate education in this country. Their values include this tendency to value religious (and, in the more secular modern era, ideological) conformity above family loyalty. College town people don’t have their cousins’ phone numbers memorized. They want to go to the government, not their relatives, when they’re too broke to manage basic living expenses. They despise nepotism and have a concept of identity in which personal, individual, chosen characteristics account for far more than ancestry and upbringing. (An unrealistic amount if you ask me.) The very notion of “reinventing oneself” is theirs. They have a powerful ethic of thinking before you speak and making sure that your every word and deed reflects your chosen identity. People who speak spontaneously, exposing the natural unrefined bundle of almost random impulses that constitutes the real human psyche, are at risk of being diagnosed with a mental health issue.

This is why they don’t get Uncle Charlie. They don’t know about how the Southern ethic of family and community loyalty forms a kind of container in which people are free to be inconsistent, to mix the awful with the wonderful, knowing that it won’t cost them anything beyond a little social embarrassment. It’s also why they don’t get Robert E. Lee. His struggles are literally incomprehensible to them.

True, true, true. Thank you, Joan; you get how we are down here.