Pop Culture’s Erasure Of Religious People

For your holiday watching pleasure, Showtime offers Work In Progress, a program described by the cable channel thus:

Abby is a 45-year-old self-identified fat, queer dyke whose misfortune and despair unexpectedly lead her to a vibrantly transformative relationship. Chicago improv mainstay Abby McEnany co-created and stars in this uniquely human comedy series.

I watched the trailer. The vibrantly transformative relationship is with a transman (female presenting as male). So there’s that. For TV watchers who like this sort of thing, this is exactly the sort of thing they like.

Still, you gotta admit: could there possibly be a more niche program? Meanwhile, I’m struggling to come up with a single show on American TV that centers itself on the lives of religious people, as religious people. Israeli TV had a dramatic series called Shtisel — trailer here — which ran from 2013 to 2016, based in an ultraorthodox Jewish community in Jerusalem. It’s streaming on Netflix here. It’s really, really interesting. It presents its characters as fully imagined people, living out ordinary lives within the boundaries of strict orthodox religion. You don’t have to be Jewish to get into this show. Watching the joys and sorrows and anxieties of Shtisel‘s imperfect, all-too-real characters kept making me think, “Yep, that’s what it’s like to live with God, and with other people who live with God.”

Seriously, give the show a chance. It takes the lives of conservative religious folks quite seriously — and that means that it doesn’t condescend to its characters by making them saints or villains.

When you think about it, it’s really incredible that there are no TV shows in the US like this — not about Orthodox Jews, not about Southern Baptists, not about Catholics, not about anybody. There are tens of millions of religiously observant people in this country — no doubt vastly more than the potential audience for a comedy about a middle-aged fat, queer, unlucky dyke — and yet, we are invisible to Hollywood.

The only TV show I have ever seen in which the kind of people I come from were depicted was NBC’s great series Friday Night Lights, which is about life in a small Texas town. As much as I loved that series, the only false note in the whole thing was its depiction of religion. They showed some of the characters going to church from time to time, but religion in this program was vague in a way that it simply isn’t in small Texas towns. You could tell that the writers knew a lot about small-town life, but on religion, they were blind as bats. Not hostile to it, mind you, just insensible.

Back in 2013, when my memoir The Little Way of Ruthie Leming came out, there was some talk about making a movie or TV series of it, but that didn’t go anywhere. It did give me the opportunity to think about how I would turn the story into a compelling dramatic series. I thought about it as a way to showcase a complex way of life that people rarely if ever get to see on American television — and one where religion was a big part of the narrative.

In the book, my sister Ruthie dies about halfway through the story. It’s easy to see how to make a movie out of that, but a series? As I conceived it, the city brother (me) moves home with his wife and kids to the rural small town immediately after his sister’s terminal diagnosis. This sets up dramatic tension, as the family’s own deep conflicts, buried for over two decades by the brother’s living far away, rise to the surface, but also — and this is where I thought it might have something fresh and interesting to say to audiences — the clash between changing Americas would be made manifest.

What I thought would be most interesting about this set-up is that it wouldn’t be a clash between a liberal sibling and a conservative sibling, but a drama between two kinds of conservatives. This was how it really did shake out in my family, though obviously without my sister present. To speak generally, my Louisiana family held firmly to the belief that if they only kept living by norms only slightly changed since the 1950s, they could keep modernity at bay. I had been out into the Real World™ and saw that this was not really possible, and came home with a bunch of ideas about how to preserve the things we valued most — family, a sense of place, and, I thought, religion — amid a churning world. In real life, there was a tremendous, near-constant clash between these two visions.

Back then, I imagined how this series would handle religion. I was not interested in a Friday Night Lights depiction of religion, where church is the place characters show up every now and then. I wanted to go deeper. Ruthie and I lived such different religious lives — and different from the religious lives of our parents. Our folks weren’t particularly observant — pretty much Easter and Christmas Methodists. I grew up to become an agnostic, then a religious seeker, ending up in Catholicism, which was strange to my family, and then Eastern Orthodoxy, which was about as extreme as you could get to them, and still be within the Christian fold. Ruthie, as a wife and mother, became what neither of us were as kids: a regular churchgoer. Her kids grew up in the church. After she died, the oldest left Christianity, the middle one became devoutly Evangelical, and now the youngest, a senior in high school, is heavily involved in a non-denominational charismatic church in town.

As regular readers know, my wife and I helped to start an Orthodox mission in town, but it didn’t last; after three years, we closed up shop, because though my home parish (county) is friendly to Christianity, and people were encouraging about the mission, Orthodoxy was a flower too exotic to grow in that soil. This was a disappointment, but not a surprise. Still, our life as Orthodox Christians in a small Southern town sparked some interesting reflections on what it meant to be a Christian in the 21st century. For example, our priest, Father Matthew, who came in with his wife and young children from the Pacific Northwest, once took his vestments to the dry cleaners in town to be laundered. Orthodox vestments are elaborate. The young black woman behind the counter said to him, “Oooh, those look like they got God all over ’em!” The two ended up talking about the symbolism of Orthodox priestly vestments, and to the shock and delight of our priest, this young black woman from the rural South knew the Old Testament Scripture verses that Orthodox Christianity draws on to construct its priests’ liturgical garments.

Now that is a fascinating American story about religion in daily life. To add to it, I bet very few white Christians in town would know those Scriptures, though once upon a time they probably would have. That’s a story too. Whites and blacks don’t go to the same churches there, but it’s not a simple matter of racism, as it would no doubt appear to outsiders. It is at least as much now a matter of very different worship styles — styles that came down from the past, and the aesthetics of which represent deep differences in black culture and white culture, and the way each approaches God. And yet, in real life, an outsider priest representing an ancient form of Christianity alien to this land comes to the dry cleaners in a small Southern river town, and unexpectedly finds rich communion with a rural black Baptist, over designs in church clothes.

You see what I mean? There are so many interesting stories to tell about religious life in America — and not just “inspirational” stories, either. I remember back in the early 1990s, when I told my father that I was converting to Catholicism. He was upset by it, not because he had anything against Catholics (the Catholic parish in our predominantly Protestant parish is older than any other church in town), but because to him, religion was about family. We don’t go to church much, and the church we don’t go to is the Methodist church, because it is the Dreher Family At Prayer. Around that time, when a bunch of new people started moving into town, my dad was really put out to show up at church one Sunday and see that the “Dreher pew” (third from the front, on the left side of the church) was filled out with people he didn’t recognize.

“But Daddy, y’all don’t go to church that much,” I told him. “Those people don’t know that that’s the Dreher pew.”

He genuinely didn’t understand what I was saying. At the time, I thought it was an example of Daddy being hard-headed. Years later, I realized that there was something very deep in his reaction. For him, religion had almost nothing to do with theological propositions. It was about family ritual, and about placing the family within God’s order. To see newcomers sitting in the traditional family pew was, to him, an act of transgression. It looked silly to me at the time, but eventually thinking about that helped me to understand why he took my leaving the Methodist church for Catholicism as a personal insult — as disloyalty to the family. And it helped me understand why he was powerless to prevent the religious churn that captured his son, and his granddaughters. I think this explains a lot of the religious churn in America, where almost half the people alive today are not affiliated with the church or religion into which they were born. My dad, who died in 2015, simply was not prepared to live in a world in which religion came to be seen as an individual’s choice.

Eventually he stopped going to church, years before he was physically unable to do it. He refused a church funeral, for reasons that I don’t really understand. And yet, in the last five years of his life, though he rarely crossed the threshold of a church, Daddy prayed more and read the Bible more than he ever did.

People are so mysterious, aren’t they? Man, I tell you, religious life in America is fascinating. You hear secular liberals from time to time blaming conservative people, and religious conservatives in particular, for our own cultural marginalization in film and television. No doubt a lot of that is true. But I don’t believe it’s mostly true. As someone who has worked in professional journalism for thirty years, I have seen up close and personal how much journalistic gatekeepers — editors and publishers — genuinely agonize over how to get more ethnic minorities, women, and gay people into journalism. They spend lots of money and energy on these efforts, year to year — even in a time of greatly declining revenues.

But they never — and I mean never — talk about how to bring religious believers, especially conservative ones, into newsrooms as reporters and editors. They don’t even see this as a problem, even though there are few places in America more secular and liberal than newsrooms. We are the problem minorities to them. We are the people who represent What’s Wrong With America. And you know, some of us do represent what’s wrong with America. Some of us represent the best of America. Most of us live somewhere in between — just like black Americans, Latino Americans, gay Americans, and everybody else. The point is, we’re here, and our lives have meaning, depth, dignity — and narrative complexity.

Why doesn’t anybody who makes movies or TV want to explore this? I’m not interested in watching pro-Christian, or pro-conservative, propaganda, and certainly not interested in watching a show about generic “spirituality.” I’m just saying that there has to be a more significant audience for a serious drama about the lives of religious believers in contemporary America than there is for a comedy about a 45-year-old self-identified fat, queer dyke, or about a family whose aging patriarch begins to present as a woman (Transparent). This is not an either-or situation — either make the fat dyke comedy, or the drama about the joys and sorrows of conservative people who take God seriously. This is a big country. There’s room for both.

And call me crazy, but if profit is the bottom line, I think there is a lot more money to be made in the religious drama. Transparent won all kinds of awards, and got massive buzz and press attention during its run, but it drew only 1.49 million viewers — a drop in the bucket. Look at this, from Daily Variety, about that show’s low ratings:

That places “Transparent” on a much different, much lower plane than the one occupied by that highest-rated streaming series that Symphony measured: Netflix’s “Fuller House.” The ’90s sitcom revival averaged an 11.31 demo rating and 21.51 million total adults.

Among the other half-hour streaming originals that out-rated “Transparent” were Netflix’s “The Ranch” (4.34, 9.54 million); “F is for Family” (3.47, 7.01 million); “Master of None” (3.28, 5.85 million); “Love” (2.18, 4.09 million); “Flaked” (0.97, 2.07 million); and “With Bob & David” (1.04, 1.98 million); as well as Hulu’s “The Mindy Project (0.88, 1.63 million).

I’ve never seen Transparent, but heaven knows I know all about it. Press coverage was everywhere. I have never heard of thee other programs — well, I did read something about Master of None, because it starred Aziz Ansari — but most of those shows had a lot more viewers than Transparent, but only a fraction of the media attention, and certainly none of the prestige in the industry.

Liberals who like to say that the film and television industry is driven entirely by market demands, and if there are no TV shows or movies featuring conservative and/or religious characters, it’s because there’s no interest in them — they don’t know what they’re talking about. There’s a reason why religious conservatives — and political and social conservatives — have been erased in film and television, and it has to do with the fact that the cultural gatekeepers don’t want to see us, except as a problem.

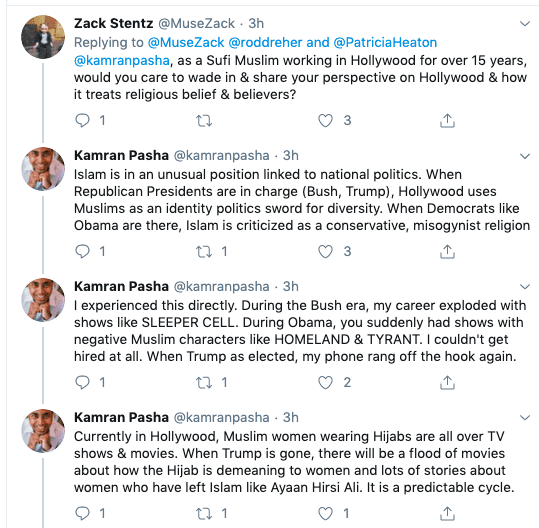

UPDATE: Got into an interesting Twitter discussion about this post. Zack Stentz is the co-screenwriter of Thor and X-Men: First Class, the writer of TV’s The Flash, and other shows:

I would love to see a serious drama about American Muslim life, but Kamran Pasha’s remarks make me doubt that Hollywood can see them as anything but political ciphers.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.