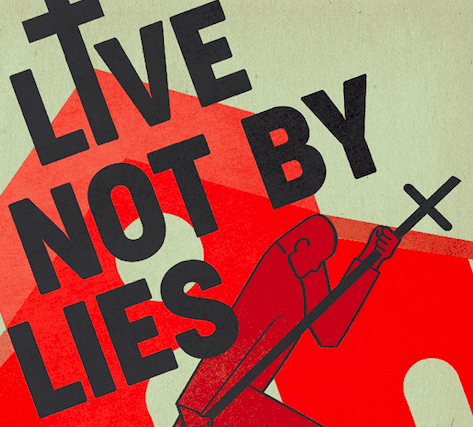

‘Live Not By Lies’ On The Front Porch

Let me apologize to you readers who are sick to death of Live Not By Lies stuff. We are just days away from the book’s release, so naturally I’m going to start posting some of the reviews the book gets. If you’re not interested, please skim past.

Here’s a pretty favorable review by James Clark in Front Porch Republic. He liked the book, but I’m going to quote a couple of his criticisms, or at least observations, to answer the questions he implicitly poses. Clark writes:

(Notably, Dreher does not recommend Christians divest themselves of their invasive technology, although his argument suggests such action would be advisable. This is probably because doing so would at a stroke destroy the careers and daily lives of millions. Also, as he himself remarks, “unless you are a hermit living off the grid, you are . . . thoroughly bounded and penetrated by the surveillance capitalist system” [77]. Even so, it would have made sense to discuss how people can cut down on invasive tech at least to some degree. For example, that products such as smart speakers are utterly superfluous is something everyone should be able to agree on, but it would also pay to remember that even ubiquitous devices like smart phones only became mainstream just over ten years ago. To claim we cannot live without them says more about us than it does about reality.)

Yes, I didn’t specifically direct people to do this because I thought it would be obvious. Here is a key passage in the book:

Kamila Bendova sits in her armchair in the Prague apartment where she and her late husband, Václav, used to hold underground seminars to build up the anti-communist dissident movement. It has been thirty years since the fall of communism, but Bendova is not about to lessen her vigilance about threats to freedom. I mention to her that tens of millions of Americans have installed in their houses so-called “smart speakers” that monitor conversations for the sake of making domestic life more convenient. Kamila visibly recoils. The appalled look on her face telegraphs a clear message: How can Americans be so gullible?

To stay free to speak the truth, she tells me, you have to create for yourself a zone of privacy that is inviolate. She reminded me that the secret police had bugged her apartment, and that she and her family had to live with the constant awareness that the government was listening to every sound they made. The idea that anybody would welcome into their home a commercial device that records conversations and transmits them to a third party is horrifying to her. No consumer convenience is worth that risk.

“Information means power,” Kamila says. “We know from our life under the totalitarian regime that if you know something about someone, you can manipulate him or her. You can use it against them. The secret police have evidence of everything like that. They could use it all against you. Anything!”

Kamila pointed out to me the scars along the living room wall of her Prague apartment where, after the end of communism, she and her husband had ripped out the wires the secret police used to bug their home. It turns out that no one in the Benda family uses smartphones or emails. Too risky, they say, even today.

Some might call this paranoia. But in light of Edward Snowden’s revelations, it looks a lot more like prudence. “People think that they are safe because they haven’t said anything controversial,” says Kamila. “That is very naive.”

Everything in the book’s chapter on surveillance capitalism and its technologies ought to make very clear to any reader: divest yourself of it as much as you can. The Bendas don’t use smartphones. Most of us, I’d wager, won’t go that far — I’m trying to decide if I can afford to do so and still do my job — but all of us can refuse to put Alexas in our houses. All of us can afford to refuse any “smart” devices. Any device called “smart” is gathering data on you, and reporting it back to someone. This is not paranoia; this is the way companies do business today. This is not prophesying a world that is coming into being; it’s already here. They are working on technology that will allow smart TVs to read the faces of those watching, and record the moments during commercials where the viewer has particular emotional reactions. I’m serious. Read Shoshanna Zuboff’s The Age of Surveillance Capitalism to learn more.

If the government were imposing this on us, we would all freak out and scream, “Big Brother!” But because it’s coming to us from Big Business, in the form of making our lives easier and more convenient, we open the door to it. Jake Meador wrote me yesterday to say, “I wonder what the Bendas would say about this device.” Here’s what it is:

Ring latest home security camera is taking flight — literally. The new Always Home Cam is an autonomous drone that can fly around inside your home to give you a perspective of any room you want when you’re not home. Once it’s done flying, the Always Home Cam returns to its dock to charge its battery. It is expected to cost $249.99 when it starts shipping next year.

Jamie Siminoff, Ring’s founder and “chief inventor,” says the idea behind the Always Home Cam is to provide multiple viewpoints throughout the home without requiring the use of multiple cameras. In an interview ahead of the announcement, he said the company has spent the past two years on focused development of the device, and that it is an “obvious product that is very hard to build.” Thanks to advancements in drone technology, the company is able to make a product like this and have it work as desired.

I can see the non-nefarious argument for buying one of those things. But look: the very presence of it in our lives creates a habitus in which we are all conditioned to accept surveillance as normal. I didn’t have the space to go into this in Live Not By Lies, but in Zuboff’s book, she talks about how “smart house” technology, which is becoming normative, does helpful things in our homes (e.g., helps a house “learn” how to save energy), but also transmits all kinds of data about our dwellings to corporations. Maybe they’ll use it innocently. Kamila Bendova doesn’t think so. Information means power.

More from James Clark’s review:

Many of these practices should sound familiar, given that they are reminiscent of The Benedict Option. But Live Not by Lies is not simply a rehash. Indeed, Dreher’s belief that liberalism is dying—more prominent here than in his previous book—helps to explain some of the ways his thought appears to have shifted since The Benedict Option was published.

For example, Dreher barely even mentions religious liberty in Live Not by Lies, whereas in The Benedict Option he contends that “religious liberty is critically important” (84). While he does not expressly recant this view in Live Not by Lies, its general absence as a topic is conspicuous. It is easy to get the impression that he has come to believe there is no point in harping on such a liberal ideal as religious liberty when more and more of those who are in power are “militantly illiberal” (93) and thus “shove aside liberal principles like fair play, race neutrality, free speech, and free association as obstacles to equality” (34). As such, “they will not even understand why they should tolerate dissent based in religious belief” (xiii).

Relatedly, Dreher’s declaration that “wherever we hide, they will track us, find us, and punish us” (68) can be understood as an acknowledgment of one of the most frequent criticisms of the Benedict Option, namely that those who are hostile to traditional Christianity have no intention of allowing us to practice our “countercultural way of living” (Benedict Option, 2). If Christians cannot count on their religious liberty being protected, and if they have “virtually nowhere left to hide” (Live Not by Lies, xiii), then they must do as the Eastern European churches (and, for that matter, the early Christians) did and “build the underground church.”

I don’t mention religious liberty in Live Not By Lies mostly because the book is not focused on politics and law. Yet I think Clark is probably onto something that wasn’t as clear to me when I wrote the Ben Op: that ultimately, the respect for religious liberty and free speech — both core liberal values — is going to fade. The last three years have made that even more clear.

As you know, my greatest frustration with the Benedict Option project is the way people who have never read the book assume that it counsels heading for the hills to build communes where they will leave us alone. I have tried to understand why so many people feel the urge to believe that, despite the fact that it’s not true. In the very first chapter, I quote theologian Ephraim Radner saying there is no place to hide from modernity! My theory is that it is a way of rationalizing their complacency, and/or their belief that we have no choice but to keep doing what we’re doing.

The truth is that the need for and the function of the Benedict Option can be seen in the film A Hidden Life. Nazism even found its way to Franz Jägerstätter’s tiny village high in the Austrian Alps. Even his fellow Catholic churchgoers fell under its spell.But because Franz and his family had been living a life of serious spiritual discipline, they saw Nazism for what it was, and found the strength to resist it, even though it cost them the respect and friendship of their neighbors, and even though it ultimately cost Franz his life.

In Live Not By Lies, I talk about this. Excerpt:

A Hidden Life makes clear that the source of their resistance was their deep Catholic faith. Yet everyone in the village is also Catholic—yet they conform to the Nazi world. Why did the Jägerstätters see, judge, and act as they did, but not one of their fellow Christians?

The answer comes in a conversation Franz has with an old artist who is painting images of Bible stories on the wall of the village church. The artist laments his own inability to truly represent Christ. His images comfort believers, but they do not lead them to repentance and conversion. Says the painter, “We create admirers. We do not create followers.”

Malick, who wrote the screenplay and who was trained in philosophy, almost certainly draws that distinction from the nineteenth-century Christian existentialist Søren Kierkegaard, who wrote Jesus didn’t proclaim a philosophy, but a way of life.

Christ understood that being a “disciple” was in innermost and deepest harmony with what he said about himself. Christ claimed to be the way and the truth and the life (Jn. 14:6). For this reason, he could never be satisfied with adherents who accepted his teaching—especially with those who in their lives ignored it or let things take their usual course. His whole life on earth, from beginning to end, was destined solely to have followers and to make admirers impossible.

Admirers love being associated with Jesus, but when trouble comes, they either turn on him or in some way try to put distance between themselves and the Lord. The admirer wants the comfort and advantage that comes with being a Christian, but when times change and Jesus becomes a scandal or worse, the admirer folds. As Kierkegaard writes:

The admirer never makes any true sacrifices. He always plays it safe. Though in words, phrases, songs, he is inexhaustible about how highly he prizes Christ, he renounces nothing, will not reconstruct his life, and will not let his life express what it is he supposedly admires. Not so for the follower. No, no. The follower aspires with all his strength to be what he admires. And then, remarkably enough, even though he is living amongst a “Christian people,” he incurs the same peril as he did when it was dangerous to openly confess Christ.

The follower recognizes the cost of discipleship and is willing to pay it. This does not mean that he is obligated to put himself at maximum peril at all times, or stand guilty of being an admirer. But it does mean that when the Gestapo or the KGB shows up in his village and demands that he bow to the swastika or the hammer and sickle, the follower will make the sign of the cross and walk with fear and trembling toward Golgotha.

So, The Benedict Option never was meant to be a safe refuge from modernity, as any reader of that book can see. It is rather an argument for and an exhortation to build communities that can prepare Christians to be disciples, not admirers, and therefore to be the kind of people who can both discern evil when it shows its face among us, and resist it, no matter what.

More from the review:

Another possible development that seems to stem from Dreher’s greater emphasis on the death of liberalism concerns his treatment of reason. While he observes in The Benedict Option that “logical reason is doubted and even dismissed” (119) in our time, his skepticism toward the effectiveness of reason is even stronger in Live Not by Lies, where he suggests that attempting to convince our illiberal opponents through “secular liberal discourse, with its respect for discursive reasoning” (62) is a waste of time: “Some conservatives think that SJWs [social justice warriors] should be countered with superior arguments and if conservatives stick with liberal proceduralism they will prevail. This is a fundamental error that blinds conservatives to the radical nature of the threat” (63). The implication is that just as our opponents care nothing for liberal ideals, they have equally little regard for reason.

If we cannot reason with our opponents, it seems to follow there is little we can hope to accomplish in the realm of conventional electoral politics. This might be why in Live Not by Lies Dreher continues his support for what he calls the “parallel polis”—understood as “an alternative set of social structures within which social and intellectual life could be lived outside of official approval” (121)—but without the affirmation of “traditional politics” that was present in The Benedict Option (78, 82–83).

This is a fair and insightful comment. Prof. Daniel Mahoney said in his quite positive review that the only thing he wishes had been in the book was more hope expressed towards the possibility of positive political action. That too is fair. I don’t mean to be read as saying voting doesn’t matter. I mean look, Amy Coney Barrett is being nominated for the Supreme Court because we have a Republican president.

My overall point, though, is that in a democracy, the government will ultimately govern according to the wishes of the majority. We know that younger generations — Millennials and Gen Z, and those to come, no doubt — are far more secular, far more liberal on social issues, and far more illiberal on tolerating dissent. Even more important, the illiberal left controls almost all the high ground among elites, institutions, and elite networks. How anybody could have lived through events of this year, and seen how impossible it is even to reason with these zealots (a bellwether example from 2015: look at Prof. Christakis trying to reason on the quad at Yale with a hysterical mob of social justice warriors) is beyond my ability to comprehend. It would be a mistake to think that there is no good to be done in conventional politics, but it would be a far, far more consequential mistake to think that somehow we can turn this around by voting for more Republicans.

The future of this country and its people, and of the churches, is being determined far more by the technology we accept, and how it shapes us individually and communally, than by those for whom we vote. This is a hard lesson for people to grasp, but it’s true.

One more excerpt:

In closing, when The Benedict Option was published, multiple commentators—and some people quoted in the book itself—observed that the vast majority of its practices simply amounted to the church being what it always has (or should have) been (142). That claim is more difficult to make about Live Not by Lies, as some of its recommendations—e.g., Christians moving underground and preparing the laity to take on the bulk of church leadership—are clearly made with extraordinary circumstances in view. Indeed, some will be inclined to reject Dreher’s ideas as overly extreme or apocalyptic.

Tempting as this reaction may be, however, I encourage readers to give Dreher a fair hearing and consider the evidence he offers in support of his arguments. The phenomena he cites are real and disquieting, and he should not be dismissed out-of-hand simply because he forecasts a world far darker than many of us believe could possibly emerge.

He’s right about that: Live Not By Lies is a darker book than The Benedict Option, even if it is ultimately hopeful. The hopefulness of the book, though, lies in a distinction I often like to make: that hope is not the same thing as optimism. Optimism says that everything is going to be just fine. That is simply not true. You would have to be out of your mind to look at the evidence and conclude, as any kind of social or religious conservative, that everything is bound to work out well for us. Hope, on the other hand, is the conviction that even if the worst comes, we can and must trust that God can use the pain and suffering of His people for the redemption of the world, even if we do not live to see it. As I say in Live Not By Lies, almost none of those who fought communism thought they would ever live to see its collapse. They resisted — and they were a minority! — because it was the right thing to do. Because that’s what it meant to be a disciple, not an admirer. I believe that when you read the stories in the book of how Christians like Silvester Krcmery and Alexander Ogorodnikov withstood their torture and imprisonment, you will see very clearly the difference between optimism and hope.

Optimism will leave us all vulnerable to collaboration and moral collapse, because it will drive us to deny reality, and then to compromise ourselves for the sake of maintaining the illusion. Only hope, of the kind that kept believers like those you meet in Live Not By Lies, will sustain us through the dark night ahead.

Read the whole review. Remember, I’ve just taken out a few points that I wanted to address. I thank James Clark and Front Porch Republic for their kind attention to my book, and for the opportunity to talk about it.

There’s still time to pre-order Live Not By Lies before its Tuesday publication date. And remember: if you want a signed copy, pre-order exclusively from Eighth Day Books in Wichita by going to this page.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.