‘A Book Worth Its Weight In Gold’

In this blog post I will talk about three really good reviews of Live Not By Lies that I want to share with you. The first is Sohrab Ahmari’s very kind take in First Things. Here’s how it begins:

In 1951, security forces in communist Czechoslovakia arrested Silvester Krčméry—and as they were taking him away, he burst out laughing. The young physician knew what he was about to face: years behind bars, shattering physical and mental torture, the loss of his professional career. Yet he also believed that “there could not be anything more beautiful than to lay down [his] life for God.” Hence, the joyous laughter that befuddled the police.

He was a disciple of the Jesuit dissident Tomislav Kolaković. Foreseeing a Red takeover, Kolaković launched an underground Catholic resistance network while World War II still raged. He called it “the Family.” As a leading member, Krčméry spent years girding himself for that knock on the door. He memorized large chunks of the Bible. His preparation served him well, preserving his faith and sustaining his spirit.

I’m so glad Sohrab led with the story of Silvester Krčmery! He and the priest Father Vlado Jukl, along with the secretly ordained bishop (later cardinal) Jan Chryzostom Korec, were the three pillars of the underground church. He was a young physician when they first hauled him off to prison, laughing. He never, ever gave up. When he was released after thirteen years, he quietly set himself to evangelizing and building up the underground Catholic church.

František Mikloško was one of those drawn to the underground church by the example of these heroes. From Live Not By Lies:

Mikloško started university in Bratislava in 1966, and met the recently released prisoners Krčméry and Jukl. He was in the first small community the two Kolaković disciples founded at the university. Christians like Krčméry and Jukl brought not only their expertise in Christian resistance to a new generation but also the testimony of their character. They were like electromagnets with a powerful draw to young idealists.

“It’s like in the Bible, the parable of ten righteous people,” says Mikloško. “True, in Slovakia, there were many more than ten righteous people. But ten would have been enough. You can build a whole country on ten righteous people who are like pillars, like monuments.”

These early converts spread the word about the community to other towns in Slovakia, just as the Kolaković generation had done. Soon there were hundreds of young believers, sustained by prayer meetings, samizdat, and one another’s fellowship.

“Finally, in 1988, the secret police called me in and said, ‘Mr. Mikloško, this is it. If you all don’t stop what you’re doing, you will force us to act,’” he says. “But by then, there were so many people, and the network was so large, that they couldn’t stop it.”

You see what personal heroism and sanctity can do? It spreads like the holy fire in the Cathedral of the Holy Sepulchre on Pascha, leaping from heart to heart, setting them aflame.

The second is from Stephen Morris on the traditionalist Catholic website One Peter Five. I think it’s possible that nobody has ever written a more favorable review of any of my books, ever. Excerpts:

Part one of LNBL offers a historical overview of how we got here, as it serves as a wake-up call to conservative Christians who think that we can somehow avoid this Pink Dawn through presidential elections, supreme court appointments, and by harkening back to our constitutional rights and freedoms. We cannot underestimate a rival that won the culture war, controls education, and now has the tyrannical overreach of big tech; this makes todays college campus radicals tomorrows political, cultural and corporate leaders. But the bigger mistake is for us to believe that we are facing merely an ideological opponent. Dreher persuasively argues that radical progressivism is actually a rival religion, replete with dogmas, purity codes and of course, an inquisitorial thirst for heretic-hunting. And this sets the table for part two of the LNBL, which locates traditional Christians in the cross hairs of this rabid progressivism.

As a reviewer, the joy of being wrong with LNBL was that I was expecting a battle plan for the coming Pink Dawn; instead I got a battle plan within a spiritual classic. Through extensive travel and interviews with Christian survivors of Communism, Dreher mines the spiritual treasures that can only be illuminated by the most unspeakable hardships. These chapters in themselves make the book worth its weight in gold as they illuminate and affirm the profound value the Christian tradition places on suffering. And this is critical because for the most part, Christians today are poorly catechized practitioners of a “Christianity without tears,” a form of therapeutic deism which will crumble in the face of actual threat. Dreher shares many strategies tried and tested in the underground churches of Eastern Europe to prepare us for travail, so as not fall prey to the trap of admiring Jesus when what He demands are followers. The kind of Christian we will be in the time of testing depends on the type of Christian we are today.

More:

This is a book of impressive scope, as Dreher successfully wears many hats: theologian, political theorist, sociologist, historian, but most importantly, prophet. Sometimes a book speaks to our times; and surely this is rare enough. Even rarer is when a book speaks to our present and our future at once. In LNBL, we are fortunate to have one of those extraordinary accomplishments in our midst. Don’t just read it: read it, and then buy a copy for each Christian in your life who thirsts to remain faithful to the deposit of faith—especially your pastor.

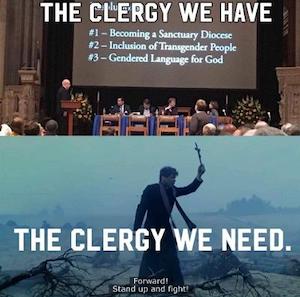

That last line reminds me of a meme that a friend sent me overnight:

That image on bottom is from a film about the life and death of Father Ignacy Skorupka, a Catholic priest from Poland who died in 1920, leading soldiers of the Polish Army in battle against the Soviet Red Army.

Harsh, but true. On one of the interviews I did this week, someone asked me if the churches were ready for what’s coming. Absolutely not, I said. Most priests and pastors, in my judgment, don’t have a clue. Maybe they don’t really want to know, either, because their preparation has not been for ministry in a time like this. We are living through the time prophesied by young Father Joseph Ratzinger, the future Pope Benedict XVI, in 1969: a time when churches would lose their people, their wealth, their status, and be reduced to a shadow of their former selves, with only a true-believing remnant remaining.

As I explain in The Benedict Option, and bring home with force in Live Not By Lies, the Christian churches are being tried in in ways that we have not seen, at least in the United States. Churches that are nothing more than chaplaincies to the Woke won’t make it. Churches that are prosperity gospellers, or in some sense the religious auxiliary to bourgeois life will not survive. Churches that are led by those who see their ministry as essentially keeping the heard calm as it is led to the (spiritual) slaughter are a clear and present danger to the faithful. Churches in which the congregation prefers not to be led by men of God who preach a bold message of repentance and preparation for hard times, but who would rather be told comforting lies — they’re going to go down. Mark my words. Look at that meme above: if your church is like the people on top, flee, and try to find one led by a priest like the one on the bottom. Whether you are a priest, pastor, or layman in your church, try to be like that fighting priest. I’m saying this to myself too; I have a lot of repenting to do from my own sins and spiritual apathy.

Let me repeat something I’ve said before: do not wait for your pastor or priest to lead on this. In 1940s Slovakia, some of the Catholic bishops thought Father Tomislav Kolaković was being an alarmist by warning Catholic students that communism was going to rule Czechoslovakia after World War II, and that the church had better prepare for persecution. They were rather clericalist, and fretted that the priest was giving too much responsibility to the laity. Father K. went about his business anyway, organizing students and preparing them — and thank God for it! Under communism, Father K.’s “Family” became the backbone of the Slovak underground church.

That meme about clergy is powerful, but a similar meme could be made about the laity. The laity on top would be those who are tattooed Christian hipsters desperate to be “relevant” to the culture, or MAGAheads eager to be fed with stale political pieties. The laity on the bottom (the laity we need) would be people like Yuri Sipko, Alexander Ogorodnikov, Silvo Krčmery, and the other Christian dissidents I profiled in Live Not By Lies.

In his long, thoughtful, somewhat critical review for ArcDigital, Justin Lee mentions the people who write me off as alarmist:

The combination of cancel culture with real political violence over the past months has startled people from all walks of political life into consciousness that something terrible is brewing. But most of Dreher’s critics seem perversely capable of indifference as the evidence mounts—as corporate America punishes states like Indiana for reaffirming federal law protecting religious freedom, as countless people are fired for holding views that were consensus or innocuous only a few years ago, as the federal government seeks to force nuns to purchase abortifacients, as Supreme Court rulings like Obergefell and Bostock threaten the dismantling of religious schools and charities (as does the Equality Act, universally supported by Democrats), as the country experiences waves of anti-Catholic and anti-Hasidic violence, as states use transgender rights as a pretense to diminish the rights of parents, as diners are assailed by white mobs and forced to pay obeisance to Black Lives Matter, and as Democrats routinely subject judicial nominees to religious tests for office.

Some critics, especially those in the church, prefer to keep their heads in the sand because to acknowledge our dire circumstances means to acknowledge their own complicity, the many ways they themselves profit from the dictatorship of lies. For others it may mean coming to terms with the imbecility of denying the threat of left-wing soft totalitarianism while melting down in public over the “actual, this-is-not-a-drill, honest-to-God-literal fascism” of Der Trumpen Führer.

Of course, there are also those who consciously lie about reality because they actually want the pink police state to come into its own. These are those for whom the “truth” is whatever narrative they believe will help them acquire power. Such people craft their public discourse according to what Dreher calls the Law of Merited Impossibility: “It will never happen, and when it does, you bigots will deserve it.” For example, those who promised that religious schools will never have their funding or accreditation threatened because of their commitment to traditional sexual ethics reneged the moment it became possible to do so.

That’s right. But Lee criticizes the book — fairly, I concede — for downplaying the dangers of totalitarianism from the Right:

Dreher is keen to scrutinize how the left destroys cultural memory in order to “reframe” history in ways that enable the implementation of its political will (e.g., The 1619 Project). One of the clearest statements of this strategy comes from a Hungarian teacher who grew up under communism: “I think they [today’s progressives] really believe that if they erase all memory of the past, and turn everyone into newborn babies, then they can write whatever they want on that blank slate. If you think about it, it’s not so easy to manipulate people who know who they are, rooted in tradition.” Although this is obviously true, Dreher seems less interested in the ways the populist right also undermines cultural memory.

Donald J. Trump is many things, but a lover of culture and history he is not. I can’t imagine there is a single monument he wouldn’t bulldoze and replace with some gilt monstrosity stamped with his phallic imprimatur. Insofar as the right embraces Trump’s impulsivity, gleeful know-nothingism, capitalist bombast, and privileging of loyalty over honesty, it participates in the same destruction of cultural memory as the left, and increases the nation’s vulnerability to totalitarian control.

To be fair, Dreher does acknowledge that “Trump’s exaltation of personal loyalty over expertise is discreditable and corrupting.” But this is the only passage in the book where Trump is mentioned, and even here the focus is on the left. From that sentence, Dreher continues: “But how can liberals complain? Loyalty to the group or the tribe is at the core of leftist identity politics. Loyalty to an ideology over expertise is no less disturbing than loyalty to a personality.” Again, this is obviously true, but we should not underestimate the extent to which Trump’s misbehavior sanctions the same from the left.

That’s a fair criticism. The reason I kept my focus on the Left in the book, and only mentioned Trump once, is because I genuinely believe the Left poses a far greater threat. Why? Two reasons: first, it really does control all the institutional high ground. As Bari Weiss writes in her terrific new essay in the Jewish magazine Tablet:

Over the past few decades and with increasing velocity over the last several years, a determined young cohort has captured nearly all of the institutions that produce American cultural and intellectual life. Rather than the institutions shaping them, they have reshaped the institutions. You don’t need the majority inside an institution to espouse these views. You only need them to remain silent, cowed by a fearless and zealous minority who can smear them as racists if they dare disagree.

There is simply nothing like it on the Right. Had we seen Trump, a man of undeniably authoritarian impulses, move towards consolidating his power in a totalitarian way, I would have written a very different book. In fact, he is a shambling mess who hasn’t gotten much accomplished. I see nothing on the American Right that can remotely compare to the power of the Left over institutional life, and the imaginations of the power elites — and that, readers, is what is going to determine our future.

Second, the Millennials and Generation Z are much less religious, far more socially liberal, and significantly less tolerant of First Amendment freedoms than are their elders. They represent the future. It’s simply not plausible that a totalitarian Right could take power. I had to make editorial decisions with this book, because I couldn’t write past a certain length. Worrying about the totalitarian Right seemed to be a real stretch.

Nevertheless, I agree with Lee here:

But there is a danger more grave than hypocrisy or persecution that Christians must take measure of, for it is a spiritual danger. As I observe Antifa, BLM, and the #resistance movement, it is clear that many people are longing for something to strive against. They need some battle in their lives in order to give it meaning, to make them feel a part of something greater than themselves. So they blow the threat of Trump and “fascism” out of proportion; they invent dragons out of lizards so they can feel like brave knights. I worry that a similar dynamic exists with much Christian fear of left totalitarianism. It is exciting to have fearful enemies. It is also revivifying. There is thus always a temptation to hyperbolize our fight. I believe that no reasonable assessment of American culture can deny that the church in America is now facing the greatest material threat in its history on this land. But I also believe that undue focus on that threat can lead to idolatry. If the church derives meaning from the battle against soft totalitarianism, it is losing that battle. As Dreher notes, totalitarianism politicizes everything; all of life is interpreted through the lens of dialectical struggle. The church should resist at all costs the temptation to define itself through a negation of the political left. The church’s identity is in Christ and Christ alone.

Great point. Those conservative Christians who seem to believe that Trumpiness is next to godliness, and that the church is little more than Lib-Owners At Prayer, are doing more to harm the church than anything coming from a Social Justice Warrior. I tell this story in Live Not By Lies:

Both come up in my conversation with Paweł Skibiński, one of Poland’s leading historians, and the head ofWarsaw’s Museum of John Paul II Collection. We are talking about what Karol Wojtyła, the great anti-communist pope, has to teach us about resisting the new soft totalitarianism.

When the Nazis invaded Poland, they knew they could subdue the country by superior force of arms. ButHitler’s plan for Poland was to destroy the Poles as a people. To do that, the Nazis needed to destroy the two things that gave the Polish their identity: their shared Catholic faith and their sense of themselves as a nation.

Before he entered seminary in 1943, Wojtyła was an actor in Krakow. He and his theatrical comrades knew that the survival of the Polish nation depended on keeping alive its cultural memory in the face of forced forgetting.

They wrote and performed plays—Wojtyła himself authored three of them—about Polish national history, and Catholic Christianity. They performed these plays in secret for clandestine audiences. Had the Gestapo discovered the truth, the players and their audiences would have been sent to prison camps or shot.

Not every member of the anti-totalitarian resistance carries a rifle. Rifles would have been mostly useless against the German army. The persistence of cultural memory was the greatest weapon the Poles had to resist Nazi totalitarianism, and the Soviet kind, which seized the nation in the aftermath of Germany’s defeat.

It’s not hard to imagine some hot-headed Polish patriot thinking that actors and playwrights weren’t doing their part in the Polish resistance, because they weren’t taking up arms against the Nazis. Maybe an analogue to our society is Christians who believe that the battle is really political. What the imaginary Polish patriot would not have recognized is that the resistance work Wojtyla and the others were doing was deep and necessary. Similarly, I think about a point a Christian friend made to me yesterday: there are lots of rich Christians who pour millions into political causes, but who do nothing for cultural strategies. My kids go to a classical Christian school here in Baton Rouge that does an incredible job on a sub-shoestring budget. This past weekend, my 14 year old daughter was reading Plato’s Republic and Augustine’s Confessions for her Sequitur classes. This is profoundly important work of preserving civilizational memory — but few if any Christian patrons help these schools. They would rather throw their money at cheap, tinselly political showmen … and then they wonder why so many young people walk away from Christianity, wondering what the point is.

Sorry for going off point. Anyway, read Justin Lee’s review. He’s very positive about Live Not By Lies; I only highlighted his criticism because I thought it was important to address.

UPDATE: I’m told by a continental European reader of Live Not By Lies that you Europeans can order it from The Book Depository (an Amazon subsidiary) in the UK, and have it delivered to you for free.

UPDATE.2: Wow, Father Andrew Stephen Damick, an Orthodox priest who is definitely the kind of cleric on the bottom of that meme, just posted Part One of his lengthy interview with Your Working Boy about living as a Christian in this post-Christian world:

INTRODUCING THE ORTHODOX ENGAGEMENT PODCAST on @ancientfaith!

LISTEN TO EPISODE #1: https://t.co/NlYuqN0jnW

For the debut episode of Orthodox Engagement, Fr. Andrew Stephen Damick interviews best-selling author and journalist @roddreher, covering his journey from… 1/4 pic.twitter.com/M9g3Q9i1Q7

— Fr. Andrew Stephen Damick (@FrAndrewSDamick) October 15, 2020

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.