A Lesson From The Spanish Civil War

Y’all know that I am a big advocate of studying the Spanish Civil War, looking for insights about where we in the US might — might — be headed, and how we can avoid Spain’s fate. If you haven’t yet watched this six-part 1980s-era British TV documentary on YouTube, please do — even if it’s just the first episode (prelude to war).

Many Americans don’t realize that the intelligentsia was, and is, heavily biased towards the Spanish Republican side, and against General Franco and the Nationalists. A reader of this blog says that the American academic historian Stanley Payne is the only reliable contemporary chronicler, in English, of the war. She sent me a new piece by Payne, in First Things, writing about the road to revolution. It’s excellent. It begins like this:

The classic theory of revolution was formulated by Alexis de Tocqueville, who observed in The Ancien Régime and the Revolution that “it was precisely in those parts of France where there had been the most improvement that popular discontent ran highest.” Revolution is not generally provoked by deteriorating conditions; rather, complaints tend to increase after conditions have already begun to improve. “The regime destroyed by a revolution is almost always better than the one that immediately preceded it, and experience teaches us that the most hazardous moment for a bad government is normally when it is beginning to reform.” The absolutist government of Louis XIV had provoked less resentment than did the milder rule of Louis XVI.

Tocqueville’s observation has been borne out by history. Modern revolutions take place not in the most traditional societies, but in polities in which a certain degree of reform and modernization has already occurred. The preliminary revolution, called by Jonathan Israel the “revolution of the mind,” consists of rising expectations. Once such attitudes have taken hold, some new crisis or setback, which may or may not be important in itself, can trigger revolution.

Revolutions succeed only where the old order is relatively weak. Because the existing regime offers little resistance, the revolution’s initial stages may be comparatively easy, not accompanied by great disorder or bloodshed. Over time, though, the revolutionary process leads to greater radicalization and greater carnage, often involving civil or foreign war. It may stimulate violent opposition and, in some cases, a counterrevolutionary movement that may be almost as radical, though with a very different program.

Spain provides the only example of a full-scale, mass, violent collectivist revolution developing out of a modern Western liberal democratic polity. The Second Spanish Republic of 1931–39 had created the first liberal democratic system in the country’s history, with, at first, impartial elections based on universal suffrage and broad constitutional guarantees of civil rights. This achievement did not prevent revolution and civil war.

Payne writes about how in the Republic, the Left refused to allow parties of the Right to participate fully — and particularly tried to repress the Catholic Church. When the Republican government in 1934 included more right-of-center parties, leftist radicals staged bloody insurrections, which were put down by the state:

In fact, the republican government enforced the mildest repression after a major revolt in Europe since the Paris Commune of 1871. But the revolutionary insurrection was justified in the press as an act of defending democracy against fascism. This agitation, international in scope, marked the beginning of the mythification of the revolutionary process in Spain, an attitude that persists in some quarters to the present day. The portrayal of revolutionary insurrection as a defense of democracy followed Trotsky’s maxim in his History of the Russian Revolution: To have the best chance, revolutionaries must appear to act on the defensive when seizing power.

The failure of direct insurrection required a change in strategy. The left began to seize absolute power through the democratic process itself, advancing revolutionary aims under the cover of legality.

After the 1936 elections revealed a Spain more polarized than ever, leftist groups began staging more violent actions. This time, though, they held institutional power:

Though they were still divided among themselves, for the next five months the revolutionary movements participated in a prerevolutionary offensive with destructive zeal. Spain was roiled by violent demonstrations, strikes, mob outbursts, acts of arson and property destruction, and the direct seizure of farmland. Local governments under socialist control often abetted and sometimes led such actions. The socialists sought to use the republican government as cover for promoting violence and social breakdown, hoping that a weak-armed reaction from the right might provide justification for a socialist-dominated revolutionary government with broad power.

After the suspicious death, in state custody, of the spokesman for the parliamentary opposition, elements of the army, led by Gen. Franco, revolted. Spain was now plunged into a savage civil war. Read it all.

Payne concludes with this lesson for us:

Revolution is not an event but a process, and a complex one. Radicals who fail to overthrow a constitutional system by force may find it useful to exploit that same system. Though their intention is to destroy the regime, they can purport to defend it when its institutions serve their short-term interests. They will invoke free speech as a cover for left-wing violence, even as they deny it to peaceful demonstrators on the right. They will honor votes unless they endanger progressive dominance, in which case the victorious right will be labelled “undemocratic.” In these circumstances, far from being a guarantee against revolutionary takeover, democratic procedures provide cover for its advance.

In Live Not By Lies, I wrote about how the Bolsheviks came to power in Russia in part because the broader middle class would not defend the autocratic system from radical challenge. Of course they were not called to defend a democracy, but autocracy. Yet that autocracy was vastly less bad than what the Bolsheviks brought to Russia. But people didn’t realize that in the pre-revolutionary years. From LNBL:

Arendt warns that the twentieth-century totalitarian experience shows how a determined and skillful minority can come to rule over an indifferent and disengaged majority. In our time, most people regard the politically correct insanity of campus radicals as not worthy of attention. They mock them as “snowflakes” and “social justice warriors.”

This is a serious mistake. In radicalizing the broader class of elites, social justice warriors (SJWs) are playing a similar historic role to the Bolsheviks in prerevolutionary Russia. SJW ranks are full of middle-class, secular, educated young people wracked by guilt and anxiety over their own privilege, alienated from their own traditions, and desperate to identify with something, or someone, to give them a sense of wholeness and purpose. For them, the ideology of social justice—as defined not by church teaching but by critical theorists in the academy— functions as a pseudo-religion. Far from being confined to campuses and dry intellectual journals, SJW ideals are

transforming elite institutions and networks of power and influence.The social justice cultists of our day are pale imitations of Lenin and his fiery disciples. Aside from the ruthless antifa faction, they restrict their violence to words and bullying within bourgeois institutional contexts.They prefer to push around college administrators, professors, and white-collar professionals. Unlike the Bolsheviks, who were hardened revolutionaries, SJWs get their way not by shedding blood but by shedding tears.

Yet there are clear parallels—parallels that those who once lived under communism identify.

Like the early Bolsheviks, they are radically alienated from society. They too believe that justice depends on group identity, and that achieving justice means taking power away from the exploiters and handing it to the exploited.

Social justice cultists, like the first Bolsheviks, are intellectuals whose gospel is spread by intellectual agitation. It is a gospel that depends on awakening and inspiring hatred in the hearts of those it wishes to induce into revolutionary consciousness. This is why it matters immensely that they have established their base within universities, where they can indoctrinate in spiteful ideology those who will be going out to work in society’s institutions.

As Russia’s Marxist revolutionaries did, our own SJWs believe that science is on their side, even when their claims are unscientific. For example, transgender activists insist that their radical beliefs are scientifically sound; scientists and physicians who disagree are driven out of their institutions or intimidated into silence.

Social justice cultists are utopians who believe that the ideal of Progress requires smashing all the old forms for the sake of liberating humanity. Unlike their Bolshevik predecessors, they don’t want to seize the means of economic production but rather the means of cultural production. They believe that after humanity is freed from the chains that bind us—whiteness, patriarchy, marriage, the gender binary, and so on—we will experience a radically new and improved form of life.

Finally, unlike the Bolsheviks, who wanted to destroy and replace the institutions of Russian society, our social justice warriors adopt a later Marxist strategy for bringing about social change: marching through the institutions of bourgeois society, conquering them, and using them to transform the world. For example, when the LGBT cause was adopted by corporate America as part of its branding strategy, its ultimate victory was assured.

What does this have to do with what Stanley Payne wrote about the prelude to the Spanish Civil War?

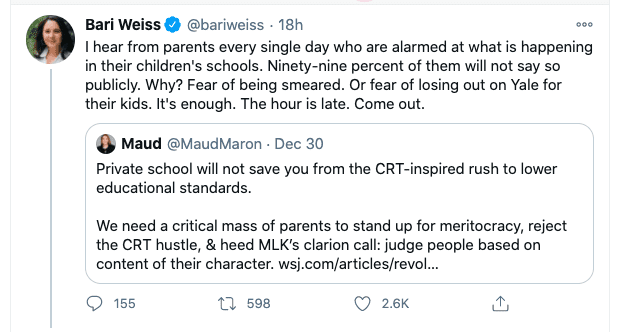

The cultural left really is marching through the institutions, and using institutional power to marginalize conservatives and moderates, and push us out. This year, we have seen an upsurge in institutional radicalization, with even the books and ideas that do not affirm the Revolution now being cast out of high schools and colleges. This is exactly how a revolution happens, even if the structures are left standing. And nobody protests! Here’s Bari Weiss, who took a costly stand against the mob, calling on people to end their silence:

If the people who understand what is happening, and how the Left is installing a soft totalitarian system while at the same time claiming to be fighting against racism, homophobia, and the rest, then we will fall. The other day I heard from a prominent conservative Christian who told me that Live Not By Lies is right on target, but that everywhere he looks he sees fellow conservative Christians who will not risk discomfort by standing up against this soft totalitarianism.

I know what you’re thinking: “If you think the Left is such a threat, why are you not out there supporting Stop The Steal, the Jericho March, and the Resistance?” The answer is because I don’t trust them at all, and because in truth, they pose no real threat to this increasingly unquiet revolution. It’s all performative with that crowd. They satisfy themselves with, “But he fights!” — ignoring that at best, Trump has only slowed down the takeover. There’s no strategy there, only emoting about God, the flag, and pillows. Instead of a Gen. Franco, a leader who seriously and effectively fought the radical left, they have produced a Gen. Flynn, the crackpot who is now openly promoting the QAnon cult.

The Right needs leadership. Desperately.

Beyond that, all of us need to wake up to where we are going if we don’t stop ourselves. The Spanish Civil War caused terrible scars in Spain, scars that are barely even scars, but still close to open wounds. This is not what we want, Left or Right. But at some point — you see this in that documentary series — the hatred and polarization was such that war was unavoidable. If you think it can’t happen here, you aren’t paying attention.