Lab Leak And Media Narrative

First, to the extent that the United States is engaged in a conflict of propaganda and soft power with the regime in Beijing, there’s a pretty big difference between a world where the Chinese regime can say, We weren’t responsible for Covid but we crushed the virus and the West did not, because we’re strong and they’re decadent, and a world where this was basically their Chernobyl except their incompetence and cover-up sickened not just one of their own cities but also the entire globe.

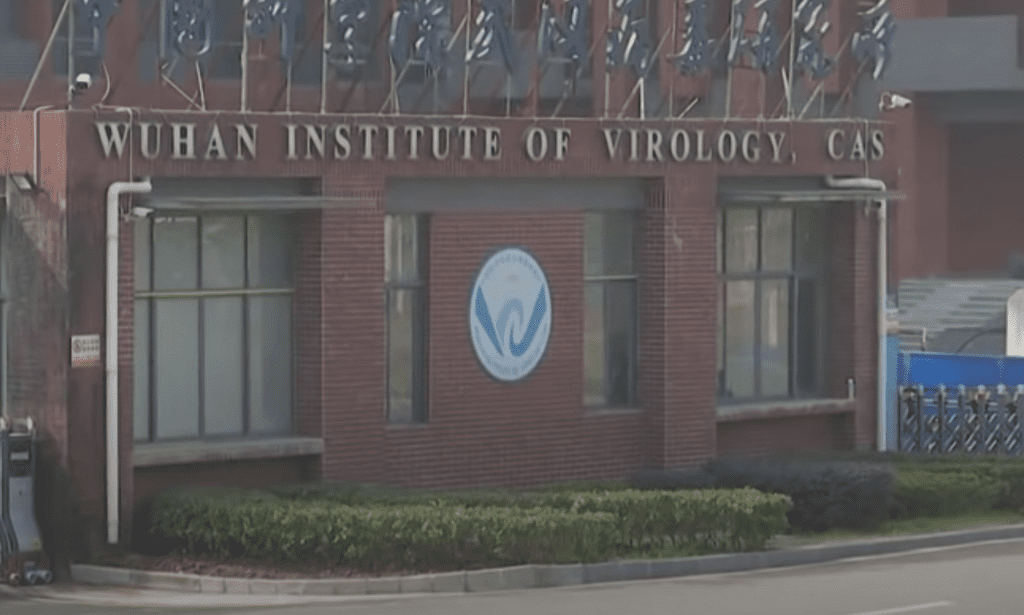

The latter scenario would also open a debate about how the United States should try to enforce international scientific research safeguards, or how we should operate in a world where they can’t be reasonably enforced. Perhaps that debate would ultimately tilt away from China hawks, as David Frum argues in The Atlantic, because the lesson of a lab leak would be that we actually need “more binding of China to the international order, more cross-border health and safety standards, more American scientists in Chinese labs, and concomitantly, more Chinese scientists in American labs.” Or perhaps instead you would have an attempted scientific and academic embargo, an end to the kind of funding that flowed to the Wuhan Institute of Virology from the U.S.A.I.D., an attempt to manage risk with harder borders, stricter travel restrictions, de-globalization.

Either way, this debate would also affect science policy at home, opening arguments the likes of which we haven’t seen since the era of Chernobyl and Three Mile Island about the risks of scientific hubris and cutting-edge research. This is especially true if there’s any chance that the Covid-19 virus was engineered, in so-called gain of function research, to be more transmissible and lethal — a possibility raised by, among others, a former science writer for this newspaper, Nicholas Wade. But even if it wasn’t, the mere existence of that research, heretofore a subject of obscure intra-scientific controversy, would become a matter of intense public attention and scrutiny.

He’s right about that, but it’s also true, as others have pointed out, that the increasingly likelihood that the lab leak hypothesis is accurate calls into question the authority of our media, including social media controllers. Discussion about the lab leak hypothesis was squelched last year because Reasons (e.g., if true, it might benefit Donald Trump; if true, it might boost anti-Chinese racism). This kind of thing happens a lot more than we think, I believe: the unconscious (or conscious) ruling out of bounds of certain discussions because they might lead to unwelcome conclusions.

I first saw this kind of thing displayed nakedly in 2002-03, in the initial wars between Catholics over the abuse scandal. On the Catholic Right, we (I was a right-wing Catholic then) avoided talking about the possibility that celibacy culture in the priesthood played a role in the scandal. We said, no doubt correctly, that there is no reason to think that a commitment to celibacy makes one more likely to sexually abuse children. But that wasn’t the claim, at least not among serious critics. The claim was that the existence of a clerical system that depended on celibacy made it easier for men who had deeply disordered sexual attraction to hide within it. It may or may not have been true, but the point is that we did not want to discuss it.

For their part, the Catholic Left ruled off-limits a discussion of homosexuality in the priesthood, and homosexual networks. You couldn’t talk about it. This prejudice was upheld by the mainstream media, and allowed a massive part of the scandal to go unexplored — and has to this day. True story: in 2002, I agreed to brief the reporter hired by Fox News to cover the Dallas meeting of the Catholic bishops — their first since the scandal broke. The reporter was a freelancer who was not a Catholic, and needed to be brought up to speed on who the players were among the bishops, and what the issues were. I prepared a thorough briefing. When I got to the part about homosexuality in the priesthood, she cut me off, and said, “We can’t go there.”

“What do you mean?” I said. “You can’t understand the scandal without understanding this aspect.”

“Sorry,” she said. “Orders from the top.” I understood her to mean Roger Ailes’s office. Not even Fox wanted to touch that third rail.

I’ve seen this happen a lot in journalism, the professional world I know best. You will never, ever see a news story exploring any negative side of LGBT life. It’s almost entirely advocacy. You will rarely if ever see a story calling into question some fundamental aspect of the so-called antiracist movement. Another true story: well over a decade ago, I once sat in a meeting of senior journalists in which the speaker was discussing survey data showing that a strong majority of particular target audience had no confidence in the media’s truth-telling. Someone in the small audience remarked, “Isn’t that said. People will only believe what they want to believe.”

Are there any other industries in which, upper management having learned that most customers or potential customers doubted the integrity of the product, a manager would react by criticizing the customers for their moral and intellectual failings? If our media truly didn’t care if reporting stories upheld the purported right-wing version of events, it would look different. But it doesn’t; in general, everything must support the Narrative.

Look:

Yes, exactly. It is staggering that it has come to this. The only story I could find about it in the mainstream media was this puff piece from NBC’s Today website,and a short, descriptive piece in the New York Post.

If it weren’t for independent media (like this blog you’re reading), you wouldn’t know that there are lots of people who are sickened and disgusted by this. Take a look at this great, gonzo interview with tech mogul Marc Andreessen, who talks about what the Internet has done for us. Excerpt:

You are a Titan of the Internet. In fact, you were inducted into the World Wide Web Hall of Fame way back in 1994. Without you there’s no LinkedIn. No Tumblr. No Reddit. No Instagram. No DeviantArt. How responsible do you feel for the horrible state of the world as it is today? Feel free to apologize to everyone.

As with everything in life, it’s a question of the counterfactual. I’m old enough to remember life pre-Internet. There were only three largely identical television networks (plus PBS if you lived near enough communists, which I didn’t), a few radio stations, a newspaper or two, three printed news magazines, a handful of book publishing houses, and a few mimeographed newsletters. That was it. We misremember the past as a Golden Age of Shared Understanding. In reality it was nothing like that; it was a time of information starvation. I think things were actually getting a lot worse in the run-up to the Internet; television was increasingly dominant, and it’s been scientifically proven that TV makes you stupid.

What does the Internet do? I think it’s clear the Internet is both an engine and a camera. To some extent it does drive behavior, but it also shows us ourselves in vivid detail. That is bound to make us uncomfortable, but is also very useful. The Internet can reinforce existing beliefs and misconceptions, but it also reveals underlying truths that otherwise would remain hidden. For example, the Internet makes it far easier to discover when an authority figure is lying to us, which is an overwhelming good.

As with any technological change, it’s important to consider who is the most threatened by it…..who freaks out the most. The Internet can be thought of as a cream that you rub on undeserving gatekeepers to drive them insane. I think it has all the right enemies.

More:

Two of your latest investments are in highly successful ventures: Substack and Clubhouse. Both have already caused some controversy, but everything is ‘controversial’ these days. Rather than focusing on pointless agendas, I’d rather turn towards the actual success from both of these ventures. Substack has taken off wildly and seems to have filled a void left behind by legacy media. There is an audience hungry for journalism that is not filtered through an ever-narrowing band of acceptable opinion, and this audience is now settling in at Substack. What are the defining features of its success, and what does this tell us not only about the state of media today, but where it is headed in light of this challenge?

The most startling aspect, to me, about the modern institutional media is its hyperconformity. (Note here, I am not criticizing the *content* of the hyperconformity; simply that it is hyperconformist. I don’t even think the hyperconformists would deny this.) This hyperconformity seems to have developed in two phases: Phase One was a collapse of previously distinct media types (network TV, cable TV, radio, newspapers, magazines, et al) into just “web sites” and now “mobile apps”. This was not their fault. Phase Two was the virtually universal industry-wide adoption of a strident ideological monoculture. This is their fault. I’m a First Amendment absolutist, so I don’t begrudge anyone the freedom to say and write what they think, but we are told that we live in a marketplace of ideas. But if you mainly consume the standard media product, what you are experiencing is closer to a marketplace of idea.

This monoculture challenges two of my most fundamental beliefs. First, in business — and these are businesses — you seek to differentiate, to offer a unique product that your customers can’t get anywhere else. In economic terms, differentiation is the key to pricing power, which is the key to profits, which is the key to staying in business. This is precisely what the existing media industry is not doing; the product is now virtually indistinguishable by publisher, and most media companies are suffering financially in exactly the way you’d expect. Second, civilizational progress happens not by top down unanimity and ideological instruction, but by debate and dispute. That this should happen, but is not happening, in the institutional media today is obvious.

And so I think it’s obvious that the incumbents are handing us, by their own considered and determinedly executed choices, a sparkling opportunity to both build better businesses and an actual marketplace of ideas. I’m intensely proud of both Substack and Clubhouse and have very high hopes that they can deliver.

For all the many problems caused by the Internet, I think one clear good is that it makes it harder for the gatekeepers to impose their Narrative. The challenge for the rest of us is to know how to tell the difference between dissident reports that tell us the truth, and those that groundlessly flatter our prejudices.

UPDATE: Read the Bret Stephens column about the media failure here. He says it all.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.