Think Tank Thomas Aquinas

Several of you readers have written to me in the past few days to note that Team Integralist seems to be trying to turn me into the new David French, and to ask if I’m okay. Um, yeah, why shouldn’t I be? The Internet is not real life. This is all tempest-in-a-teacup stuff, and somehow I think I’ll survive being off of Adrian Vermeule’s Christmas card list. I have to share with you, though, this e-mail I received this afternoon from an important GOP Congressional staffer, whose name and affiliation (meaning where he works) I’m going to withhold. I should point out, though, that this staffer is not an Establishment Republican who just wants to return to the pre-Trump status quo:

Just wanted to put in a word of appreciation for your recent writings on the future trajectory of conservatism, especially given all the blowback online from our “side.” Working in [GOP office], I’m pretty up-to-speed on current debates surrounding integralism and the direction things are headed. (I’ve read plenty of Vermeule, Ahmari, Waldstein, Crean & Fimister, and the rest.)

That crowd seems pretty far removed from the realities of the moment, so let me be very blunt here. Nobody with a day job in public policy—and I mean nobody—is going to wade through thousands of words of neo-scholasticism at The Josias in order to puzzle out how to wield political power. What the “realignment” movement really needs are practical solutions that can be translated into Overton-window-shifting legislation, and we need them right now. We need cover articles in American Affairs on topics like “A National Conservative Approach to Health Insurance.” (To his credit, Gladden Pappin at the University of Dallas has been really good about this.) This is the sort of thing that can get translated into actual legislative proposals, which “normal” people will at least discuss.

I totally get why nobody wants to do this work. This stuff is boring, and technical, and requires developing some subject-matter competence. It’s a lot more fun to take potshots at David French.

But the fascinating paradox here is that while much of the integralist crowd faults you for being unwilling to confront the challenges of the day, in practice that’s exactly what they themselves are doing! Spending endless hours building out an intricate model of the perfect Catholic regime, and the suitable conditions under which it can seize baptized children from their parents (and justifying all this time and attention by claiming they’re simply stressing the “primacy of the speculative”), is nothing more than Ph.D.-level daydreaming. It’s an air castle. But it’s an easy alternative to doing the grinding, boring, “technocratic” work of proposing and defending actual policies.

(By contrast, your Benedict Option writings offer concrete tactics for navigating current and future conditions. That’s what seems to be completely out of view in their arguments.)

If I sound annoyed, it’s because so much of the intellectual oxygen in the postliberal space is being sucked up by people who are basically just repeating the same set of high-level claims over and over and over again. Yes. We get it. We can all agree that liberal neutrality is a façade and that we need to reinvest in individual workers and defend the common good. But on the ground, we need people who can talk seriously about things like the child tax credit, the Administrative Procedure Act, and the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts. Else, we’ll be incapable of effectively wielding power when we get it.

Anyway, rant over. Just thought you might appreciate hearing from someone who’s in the trenches right now.

I do appreciate it. This echoes what I’ve been hearing privately since the National Conservatism conference from conservative Catholics and others who are in the public policy trenches: that integralism, and integralist-adjacent speculation might be an interesting intellectual activity, but it is massively disconnected from the realities we are now facing, and is at best a distraction from initiatives that might actually work.

The Republican Party is likely to retake Congress in the 2022 midterms. What is a realistic legislative agenda that could be accomplished in this actually existing country? I’m not a public policy thinker, and not really a political thinker at all. Religion and culture is my wheelhouse, which is why the Benedict Option is more about what we can do culturally — though I of course recognize that politics has to be part of the resistance (and say so in the book). But I don’t want the perfect to be the enemy of the best-we-can-do-right-now. We do need a broader and deeper vision of the Good, but something tells me that in America, it’s not going to come out of Catholic integralism.

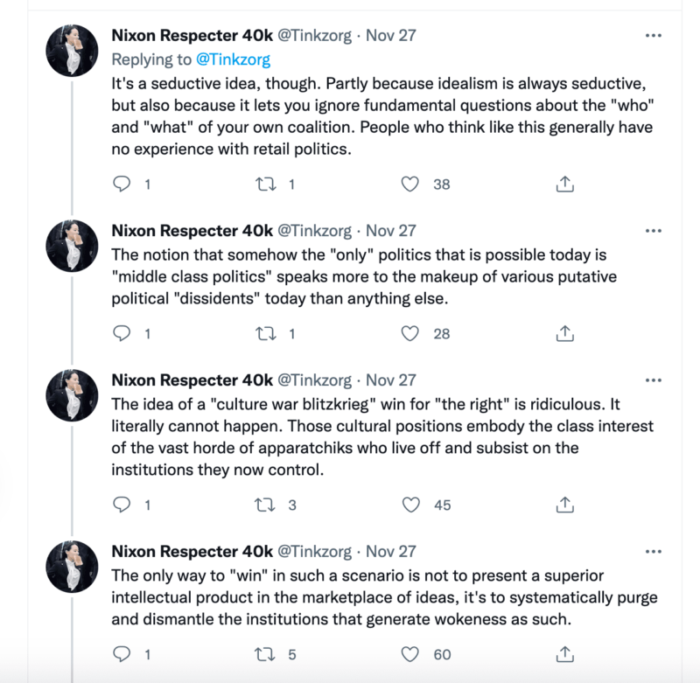

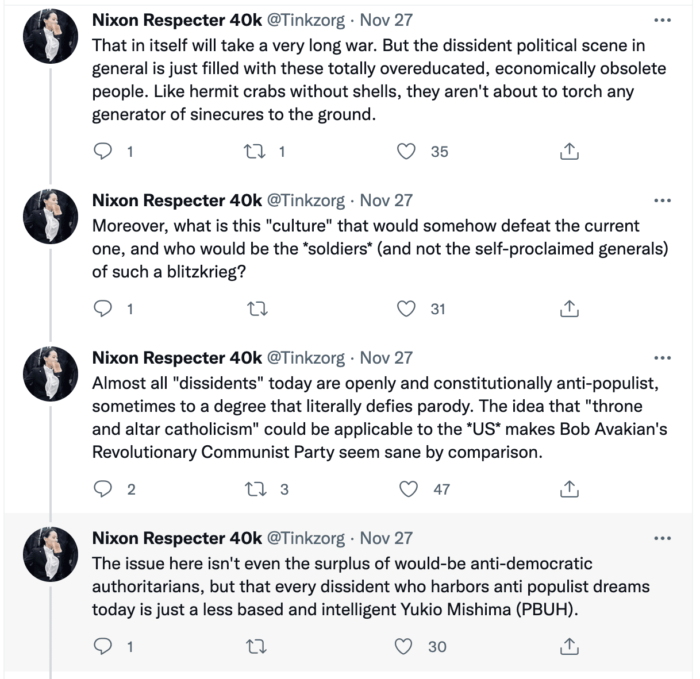

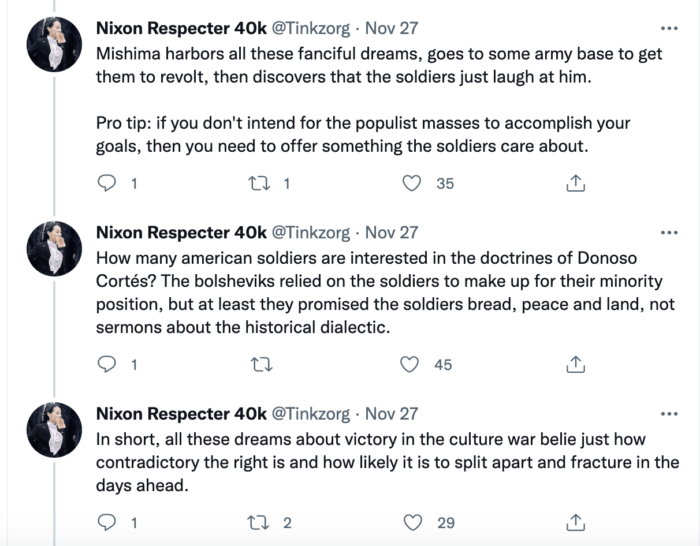

Malcolm Kyeyune has a provocative Twitter thread about this kind of thing. Excerpts:

The Right needs concrete, achievable policy proposals. But it also needs new stories, or rather, Stories. Most people think narratively. To be honest, despite all the doubts I have about late liberalism, I think the old-fashioned American story is still a pretty good one, or at least better than any competitors. I was listening earlier today to the English “reactionary feminist” commentator Mary Harrington talking about how liberalism isolates people and alienates them from each other, from their past, and from anything higher than the self — and how this is a dead end. I also listened to the Quillette podcast with Batya Ungar-Sargon in which she said that she used to be woke, and is still a socialist, but an anti-woke one. She said that she came to realize that woke progressivism is in fact class war against the poor and working Americans on behalf of the ruling elites. You don’t need to be against classical liberalism simpliciter to agree with them that the state of liberalism today is not working for the common good.

Both of these women were at the NatCon conference, though neither are conservatives. There’s some really interesting stuff going on, both intellectually and in terms of policy potential. What about new stories, though? It is incredible that the Right has allowed the toxic woke story of America to go largely unchallenged. True, the woke have almost all the media, but can’t we do better than we have been? Reheated Reaganism is not the answer, obviously, nor is an unreflective nostalgia. But it seems to me that there is still a lot to work with within the American tradition. Classical liberalism is deeply flawed, perhaps fatally, but it’s the only tradition we have in this country. Besides, we were once a country that had a lot more solidarity, even though we had classical liberalism. Unless we have a true revolution in America, our future will evolve out of classical liberalism, because that is what we know. My thought is that we should take Patrick Deneen’s excellent critique of liberalism (Why Liberalism Failed), and figure out what it has to teach us about ways that we can reform liberalism in a Burkean way — that is, building on what can be salvaged from our own native tradition.

Deneen himself (I think) believes that this can’t happen, and maybe he’s right. But if he is, then it seems to me we are much more likely to get some form of socialism in this country, or right-wing authoritarianism in a distinctly American key (e.g., the Protestant Generalissimo Michael Flynn) than anything that would satisfy the throne-and-altar integralists.

UPDATE: Reader Matt in VA comments:

What I’ve read in numerous different places by authors that I trust is that if you want new stories your best bet is an invigorating rediscovery of the old, or even the very, very old — that creativity and imagination must be fertilized, and the best fertilizer is that which comes from outside of the current moment we’re in, and so far outside of it and away from it that it escapes the narrowness and provinciality of the current time entirely. That is, what is needed is a renaissance of sorts. Why did the American founders style themselves as Romans? Surely their pretending to be Romans wasn’t directly connected to the actual experience or direct background of the people founding the country! They were English gentry and religious nonconformists and such.

We are still too close to a certain kind of Christianity for it to serve this purpose, I think. We cannot re-Christianize ourselves when most of us still see Christianity as something narrowly partisan and easily slotted into today’s stifling and endless political battles. One might wonder if the Integralists in fact recognize this, and thus look to a kind of medieval Catholicism as a potential answer precisely *because* it is distant and alien–nothing like American mainline Protestantism– but at the same time a very rich vein to mine. Who knows what will come out of the shift to an online world? When mass mediums/mass media changes as profoundly as it just has, all sorts of things become possible. Also, the Catholic Integralists perhaps recognize — to give them their due — that America now is very different from the America that was founded in the 1700s, especially in that we are an *empire* now, and perhaps *the* *empire*. Maybe we should rediscover our roots as a republic — or maybe we should just accept that what we have now is nothing like a republic. I don’t see us going back to being a republic anytime soon, do you? Catholic Integralism might indeed be suited better to a society or culture or whatever that has become what America is today.

One of the things which some of the people who have been criticizing you, including Vermuele, has pointed out, is that you keep insisting, over and over, on this idea that something has to be broadly popular with the current masses to have any political value or political use, when there is very little reason to think this is the case. You look at what Americans say they believe right now and insist that here lies the boundaries of what is politically possible. But it is small intolerant minorities who determine what happens in a society and where the boundaries or permissible vs. impermissible are drawn, not vast swathes of people who don’t ultimately really care and who are too distracted by life or too atomized to make their preferences felt. Considering how often you write about trans people and the trans phenomenon, you should, I think, understand what I mean. Trans people are some incredibly tiny portion of the population and yet MTF transgendered people punch about 1,000 times above their weight when it comes to the culture war. Or gay marriage. Gays are vastly outnumbered by straights and as recently as 2004/2006 gay marriage lost at the ballot box by 75%/25% margins — yet it didn’t matter at all. What people say they want or believe in or whatever matters very little. Social media in particular shows us all too painfully clearly that most people are desperate to be told what to believe and what to espouse, to the point where they JUMP at the chance to be consensus-seeking protozoan stimulus-response “give me memes to share to signal my ingroup/outgroup role, please — and the more the better! Content! Content! Content!” There is nothing people love more than “LOVE IS LOVE SCIENCE IS REAL WATER IS LIFE BLACK LIVES MATTER” etc etc tinned content, they slurp it up and turn themselves into rhizomatic viroid reproducers of it the way the supposedly bad old materialistic racist sexist narrow-minded Christian 1950s suburban families gobbled up middle-class commercialized “Revolutionary Road” Americana. Social media lays bare, to a degree that I think is in fact profoundly destabilizing and disillusioning, that people approach almost *everything* social from the perspective of ingroup/outgroup dynamics, swarms, fads, prefabricated copy, protozoan consensus-seeking, and threats of ostracism. Very difficult to believe in a number of things when this becomes so clear.

It is simply not true that what is politically viable is a matter of what the masses believe, or say they believe, in public opinion polls or whatever. The difficult thing is coming up with a way of taking and seizing power, of exercising power; if you’ve got that, you can do almost whatever you want!

Also: there is an interesting contrast between Tinkzorg’s claims about the practicality and hard-headedness and “populism” of the Bolsheviks, their supposed promises of peace land and bread, and the way you have consistently written about how the Russian Revolution happened on this blog. Many, many blog posts, many related to the Live Not By Lies book, argued that Communism happened/came to power because it was the OPPOSITE of a materialistic, practical, “here are practical steps we’ll take to improve the lives of the poor and the masses” movement. Blog post after blog post of yours stresses the degree to which Bolshevism was fired not at all by the masses of workers or the poor or whatever. It was driven and fired instead by the zeal of the intolerant minority, the overproduced elite, the fanatic, the criminal, the hysterical, the highly verbally fluent, etc.

Tinkzorg wants to claim that the right wing needs soldiers, not just wannabe generals — and that’s true — but I think it’s a mistake to think you get soldiers by coming up with “practical legislation” for Marco Rubio to try to pass in the Senate or whatever. I get where this is coming from — it’s a New Deal or Great Society mindset where the government cultivates a voter base or a client/patron relationship with certain groups of voters that it can rely on for votes, power, muscle, manpower, whatever, in exchange for steering money, access, etc., to that group. That’s a good model! But it has to be understand in the right light. What needs to be understood is the degree to which this model is *fundamentally* and *inextricably* incompatible with the “throw the ring of power into Mt Doom” value system of American conservatives. This model *requires* at the very most basic level a rejection of the “rejection of power” mindset. And that’s a big reason why the whole thing is such a nonstarter with the entire Republican Party as it exists today. Tinkzorg saying that Catholic Integralism won’t work because it’s a group of wannabe generals with no troops ? Well, the entire American Republican/conservative superstructure is practically designed in a lab to result in no troops! This is why American conservatives are either too scared or can’t be bothered to do literally anything other than vote in the safety of the secret-ballot-box, why anybody who counsels anything other than a Tolkienesque “long defeat” is ostracized and denounced by the respectable Right, why conservatives think even just “organizing” is shameful and low-class and a waste of time and can’t be bothered with it (or, they won’t admit, are afraid). The whole thing is set up from the start to destroy the possibility of developing an army (in the political sense.) What is that most basic truism about avoiding becoming a failed state? FEED AND PAY YOUR SOLDIERS!!!! No wonder that American conservatism, which has been telling its own voter base for decades now to drop dead Kevin Williamson-style, is in crisis and is the political party equivalent of a failed state (sacked by Trump in 2016).

it isn’t true that you need to look at what the masses say they believe in or want in public policy polls. I won’t say the masses don’t matter, but they matter a lot less than all this cant and sentimental nonsense about democracy leads us to believe. This is not to say that democracy is inherently bad but enough with these magical and obtuse fantasies about it! “Of forms of government let fools contest; whatever’s best administered is best.” If one lives in a monarchical system but the monarch mostly leaves the majority of decent/normal people alone, that is surely preferable to a rotten democracy rife top to bottom with manipulation, lying, behind-the-scenes intrigues, careful control of media, massive unaccountable bureaucracies that really determine how policy is enacted, undemocratic spook organizations shielded entirely from oversight, etc.

Tinkzorg contrasts the failure of Mishima with the success of the Bolsheviks. Fair enough. It was not very smart to attempt fascism shortly after fascism had been about as defeated as something can be on the world stage. That said, given enough time, things that were “defeated” can still pass the test of time. The ancient Greeks were defeated, and yet… Certainly it is true that we are still close enough to “fascism” for it to be a pretty poor strategy! It’s a paradox — you have to reach farther back, perhaps, to find that which can inspire the creativity and vitality that is lacking in the present. Reaching for medieval Catholicism is not necessary a mistake in that sense!

I agree by the way with the general diagnosis of Integralism as a dead end — but for me, it’s because I think the integralists are mostly rebranded neocons (Vermuele, Ahmari) who needed a new disguise/aesthetic, and there’s not really anything there, not sincerely. Vermeule’s cowritten academic piece with Cass Sunstein highly relevant here, of course. It’s worth noting that Neoconservatism was never remotely popular with the masses (not even 0.1% of voters cared about what The Weekly Standard had say) yet neocons really did exercise *tremendous* power. Another piece of evidence that it doesn’t matter if something isn’t popular with the masses — on the Republican/conservative side, that might even be an asset! The Republican base/broad voter population is so atomized/domesticated/trapped in an ideology of expecting nothing that the people who actually hold power behind the scenes in Republican administrations can be utterly opposed to them in almost everything and even hate most of them, and as long as they are good at palace intrigue they can do whatever they want.

Richard Hanania has made this point often — it doesn’t matter what the masses of Republican voters or Americans want all that much, because different types of people just matter more than others when it comes to exercising power. Certain very rare types of Republicans — neocons would be one example, and business/corporation-loving libertarians would be another– are very rare among the voting public but they matter a great deal when it comes to how power actually gets exercised. If all you do is vote, what you want will have little or nothing to do with what actually comes out of Washington, because voting (when there are only two parties in a 330 million person country) does not translate to policy choices very well, especially on the republican side (on the Democratic side there is MUCH more understanding that other things matter too like activism, organizing, pressuring others, attempting to dominate the public square, associating your opponents with low social status, etc.)

The way to understand “Integralism” is that it’s a bid to become a new sort of Weekly Standardism. It does not matter AT ALL that there’s no mass audience for this stuff, any more than it mattered that there was no mass audience for the Weekly Standard. If the integralists are attacking you, Mr. Dreher, it’s because they’re practicing the arts of ostracism, ingroup-outgroup policing, Overton Window manipulation, control of the sphere in which the “conservative braintrust” operates, etc. — all things that matter for a group or a force that hopes to gain power NOT by rallying the masses but by using palace intrigue techniques to exercise its power behind the scenes among those who actually make the big decisions. It’s not a bad strategy!

Thanks for this. There’s a lot to digest. Let me offer a couple of reactions.

I agree that a dedicated minority can determine the future, especially politically. But the Bolsheviks aren’t as good a parallel as you (and the integralists?) think. You have to consider the context in which they emerged. Marxists had been trying for decades to gain power in Russia, but got nowhere. A key event that opened the door for them was the famine of 1891-92, which the imperial government failed miserably in its response. That shook people’s confidence in the established order, and caused many who had been impervious to Marxist arguments to open their minds. Around the turn of the century the intelligentsia and the cultural elites began to turn to radicalization. The Tsar’s loss in the 1903 Russo-Japanese War further delegitimized and destabilized the monarchy. The 1905 Revolution was a prelude to what was to come in 1917.

It is also the case that industrialism, which came late to Russia, served to uproot rural masses and draw them into cities, where they worked in factories. Yuri Slezkine, in his great 2017 history The House of Government, talks about how the Marxists tirelessly evangelized in factories for the cause. They found willing listeners among masses of workers who were living shitty lives of toil, and who, having been uprooted from the village, were willing to think differently. The Bolsheviks were strong idealists, for sure, but they also offered materialist promises to improve the lot of the workers.

The reason that sexual minorities punch so far above their weight in our society is not only because they have fully captured the elites, but also because the LGBT ideology builds on what masses of Americans already believe about sex and the human person. The Sexual Revolution did the heavy lifting of separating sex from morality and social structures, and making sexual desire central to human personhood and identity. Late capitalism also separated economics from social and moral purpose. Both expressions of liberalism prize the desiring, choosing individual.

So when the gays and the transgenders come along and make their appeals to the masses, they were simply building on a well-established cultural logic in our time and place.

Do the integralists have anything similar to point to? I don’t doubt that a small minority can, under the right conditions, control history. But I don’t see the conditions present in American society — a historically Protestant polity that is de-Christianizing — today that would give people who advocate for Catholic integralism any foothold among the masses. Things could change! But for now, no.

You write:

This is why American conservatives are either too scared or can’t be bothered to do literally anything other than vote in the safety of the secret-ballot-box, why anybody who counsels anything other than a Tolkienesque “long defeat” is ostracized and denounced by the respectable Right, why conservatives think even just “organizing” is shameful and low-class and a waste of time and can’t be bothered with it (or, they won’t admit, are afraid).

Is this true? I don’t think so. Conservatives who counsel the “long defeat” aren’t lionized at all. The conservatives who are lionized are those who Own The Libs, regardless of whether they have any concrete proposals to change anything. It is enough for now, among conservative voters, to be against left-liberals. We have not yet seen a right-wing politician who can mobilize conservative and moderate voters behind a concrete policy agenda, tied to a compelling story about who we are, and who we should be.

That person might emerge. I hope so! But whoever it is will have to build on the America, and the Americans, that we have, not the ones we wish we had. As a conservative Christian, I have a fairly clear idea of the kind of country I would like to see. But I also know that some of my views are not popular with most Americans. I’m not looking for the perfect candidate.

I didn’t write The Benedict Option because I think it will appeal to most Americans. The book is premised on the idea that small-o orthodox Christianity is now, and will increasingly be, a minority belief. The most important thing is to hold on to the true faith, and to pass it on to our children, and they to their children. I hope and pray for the re-Christianization of our society. What concerns me most is that memory of the faith remains alive so that when the cult of individualism/liberalism/progressivism runs its course, there will the church be, ready to rebuild from the ruins. This is more important to me by far than politics, though I agree that politics plays a role in this drama.