Evangelicals: Who Are The Good & The Bad?

In my circles, there has been a lot of discussion about Megan Basham’s big piece about how the federal government used some high-profile Evangelical leaders to spread government information — and misinformation — about Covid to the broader Evangelical community. (If you don’t have a Daily Wire account, the piece has been reprinted here, available to all.)

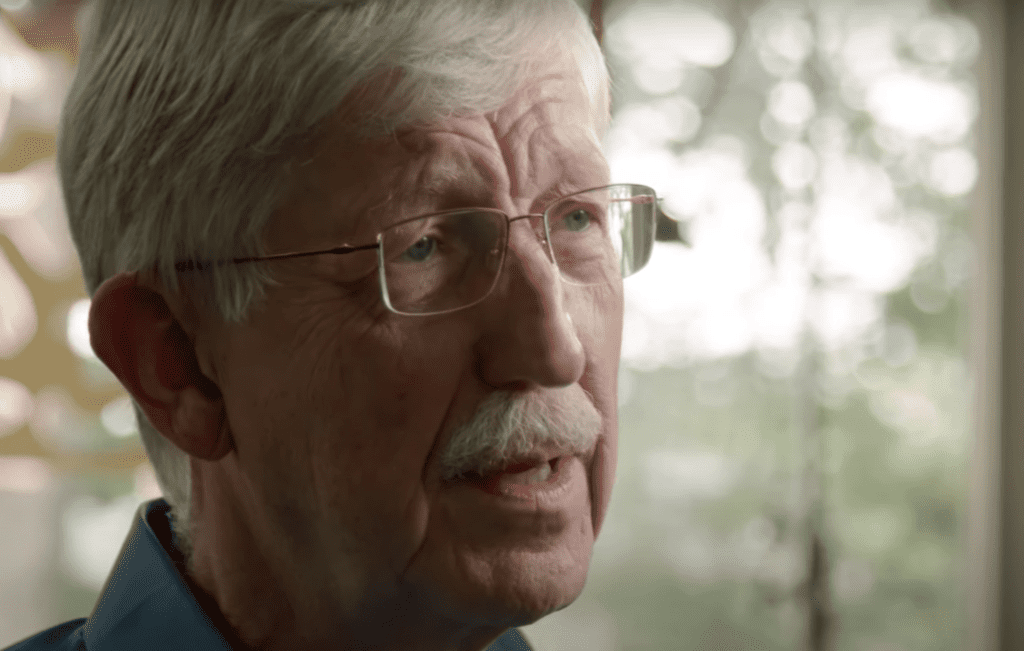

As regular readers will know, I am not an anti-vaxxer, but this is genuinely a disturbing piece. The gist of it is that the feds leveraged the high status the Evangelical scientist Francis Collins has with Evangelical influencers to sell the government’s Covid line to Evangelical churches. Basham begins by citing Wheaton College’s Ed Stetzer, a dean and executive director of its Billy Graham Center, giving a friendly interview to Collins early in the pandemic:

Stetzer’s efforts to help further the NIH’s preferred coronavirus narratives went beyond simply giving Collins a softball venue to rally pastors to his cause. He ended the podcast by announcing that the Billy Graham Center would be formally partnering with the Biden administration. Together with the NIH and the CDC it would launch a website, coronavirusandthechurch.com, to provide clergy Covid resources they could then convey to their congregations.

Much earlier in the pandemic, as an editor at evangelicalism’s flagship publication, Christianity Today (CT), Stetzer had also penned essays parroting Collins’ arguments on conspiracy theories. Among those he lambasted other believers for entertaining, the hypothesis that the coronavirus had leaked from a Wuhan lab. In a now deleted essay, preserved by Web Archive, Stetzer chided, “If you want to believe that some secret lab created this as a biological weapon, and now everyone is covering that up, I can’t stop you.”

It may seem strange, given the evidence now emerging of NIH-funded gain-of-function research in Wuhan, to hear a church leader instruct Christians to “repent” for the sin of discussing the plausible supposition that the virus had escaped from a Chinese laboratory. This is especially true as it doesn’t take any great level of spiritual discernment — just plain common sense — to look at the fact that Covid first emerged in a city with a virology institute that specializes in novel coronaviruses and realize it wasn’t an explanation that should be set aside too easily. But it appears Stetzer was simply following Collins’ lead.

Only two days before Stetzer published his essay, Collins participated in a livestream event, co-hosted by CT. The outlet introduced him as a “follower of Jesus, who affirms the sanctity of human life” despite the fact that Collins is on record stating he does not definitively believe, as most pro-lifers do, that life begins at conception, and his tenure at NIH has been marked by extreme anti-life, pro-LGBT policies. (More on this later).

But the pro-life Christian framing was sure to win Collins a hearing among an audience with deep religious convictions about the evil of abortion. Many likely felt reassured to hear that a likeminded medical expert was representing them in the administration.

During the panel interview, Collins continued to insist that the lab leak theory wasn’t just unlikely but qualified for the dreaded misinformation label. “If you were trying to design a more dangerous coronavirus,” he said, “you would never have designed this one … So I think one can say with great confidence that in this case the bioterrorist was nature … Humans did not make this one. Nature did.”

It was the same message his subordinate, Dr. Anthony Fauci, had been giving to secular news outlets, but Collins was specifically tapped to carry the message to the faithful. As Time Magazine reported in Feb. 2021, “While Fauci has been medicine’s public face, Collins has been hitting the faith-based circuit…and preaching science to believers.”

The editors, writers, and reporters at Christian organizations didn’t question Collins any more than their mainstream counterparts questioned Fauci.

Stetzer is a big deal in Evangelical circles. As Basham shows, he was far from the only big-name right-of-center Evangelical to give Collins space to make his case without challenge. Because I am not an Evangelical and don’t really live in that information space, I had no idea that this was going on. How did it happen? Basham writes that its entirely because those Evangelical elites have such admiration for Collins, who late last year announced his retirement as director of the NIH.

But why do they carry so much water for Collins? Basham writes:

Perhaps the evangelical elites’ willingness to unhesitatingly credit Collins with unimpeachable honesty has something to do with his rather Mr. Rogers-like appearance and gentle demeanor. The establishment media has compared him to “The Simpson’s” character Ned Flanders, noting that he has a tendency to punctuate his soft speech with exclamations of “oh boy!” and “by golly!”

Going by his concrete record, however, he seems like a strange ambassador to spread the government’s Covid messaging to theologically conservative congregations. Other than his proclamations that he is, himself, a believer, the NIH director espouses nearly no public positions that would mark him out as any different from any extreme Left-wing bureaucrat.

He has not only defended experimentation on fetuses obtained by abortion, he has also directed record-level spending toward it. Among the priorities the NIH has funded under Collins — a University of Pittsburgh experiment that involved grafting infant scalps onto lab rats, as well as projects that relied on the harvested organs of aborted, full-term babies. Some doctors have even charged Collins with giving money to research that required extracting kidneys, ureters, and bladders from living infants.

He further has endorsed unrestricted funding of embryonic stem cell research, personally attending President Obama’s signing of an Executive Order to reverse a previous ban on such expenditures. When Nature magazine asked him about the Trump administration’s decision to shut down fetal cell research, Collins made it clear he disagreed, saying, “I think it’s widely known that the NIH tried to protect the continued use of human fetal tissue. But ultimately, the White House decided otherwise. And we had no choice but to stand down.”

Even when directly asked about how genetic testing has led to the increased killing of Down Syndrome babies in the womb, Collins deflected, telling Beliefnet, “I’m troubled [by] the applications of genetics that are currently possible are oftentimes in the prenatal arena…But, of course, in our current society, people are in a circumstance of being able to take advantage of those technologies.”

When it comes to pushing an agenda of racial quotas and partiality based on skin color, Collins is a member of the Left in good standing, speaking fluently of “structural racism” and “equity” rather than equality. He’s put his money (or, rather, taxpayer money) where his mouth is, implementing new policies that require scientists seeking NIH grants to pass diversity, equity, and inclusion tests in order to qualify.

To the most holy of progressive sacred cows — LGBTQ orthodoxy — Collins has been happy to genuflect. Having declared himself an “ally” of the gay and trans movements, he went on to say he “[applauds] the courage and resilience it takes for [LGBTQ] individuals to live openly and authentically” and is “committed to listening, respecting, and supporting [them]” as an “advocate.”

These are not just the empty words of a hapless Christian official saying what he must to survive in a hostile political atmosphere. Collins’ declaration of allyship is deeply reflected in his leadership.

Under his watch, the NIH launched a new initiative to specifically direct funding to “sexual and gender minorities.” On the ground, this has translated to awarding millions in grants to experimental transgender research on minors, like giving opposite-sex hormones to children as young as eight and mastectomies to girls as young as 13. Another project, awarded $8 million in grants, included recruiting teen boys to track their homosexual activities like “condomless anal sex” on an app without their parents’ consent.

Other than his assertions of his personal Christian faith, there is almost no public stance Collins has taken that would mark him out as someone of like mind with the everyday believers to whom he was appealing.

I once heard an Evangelical say that Collins, by virtue of his scientific brilliance and his having risen to the heights of the scientific bureaucracy in the US, is seen by many Evangelicals as a living refutation of the prejudicial belief that you can either be smart, or you can be an Evangelical, but you can’t be both. In other words, Collins helps Evangelicals get over their cultural inferiority complex, according to this view. Maybe so.

Here is the takeaway from Basham’s piece:

Francis Collins has been an especially successful envoy for the Biden administration, delivering messages to a mostly-Republican Christian populace who would otherwise be reluctant to hear them. In their presentation of Collins’ expertise, these pastors and leaders suggested that questioning his explanations as to the origins of the virus or the efficacy of masks was not simply a point of disagreement but sinful. This was a charge likely to have a great deal of impact on churchgoers who strive to live lives in accordance with godly standards. Perhaps no other argument could’ve been more persuasive to this demographic.

This does not mean these leaders necessarily knew that the information they were conveying to the broader Christian public could be false, but it does highlight the danger religious leaders face when they’re willing to become mouth organs of the government.

This seems to me to be a very important piece, one that all of us, even non-Evangelicals, should take seriously. Why? Because it shows how we can allow ourselves to be used and deceived by those in whom we place authority. Though Evangelicalism is not my world, nor is science, I have for years uncritically assumed that Francis Collins was a Good Guy™, was One Of Us™, and so forth. Why? Because others I knew and trusted said so. That was it. It really was. That Collins was so useless as a Christian when it came to the ways he ran NIH came as a shock to me when I first read about it last fall. I assumed that because the people I know and trust vouched for him, he must be fine.

We all do this, and we have to do this, because nobody can get through life being radically skeptical of everybody else. All of us have a network of people we trust as authoritative. What none of us really know, though, is whether or not those who have our trust deserve it. This was a lesson learned quite painfully by many American Catholics, who believed for decades that their bishops could be trusted on the sex abuse scandal, when in fact many of them were flat-out liars who had no problem punishing victims and victims’ families, and deceiving the wider church, to protect their own high positions, and sometimes their gay clerical networks. My point is that whether you are Evangelical or some other kind of Christian, whether you are religious or an unbeliever, and whether you are on the Left or the Right, at some point you rely on the personal authority of certain figures — and you may find out that that was a terrible mistake. Grift runs very deep within human institutions.

Today The New York Times published a long essay by my friend David Brooks, titled, “The Dissenters Trying To Save Evangelicalism From Itself”. I’m not sure if David would claim to be an Evangelical, though he has shared publicly that he considers himself to be a Christian, but he certainly is friends with some of the people he profiles in the piece, and there’s no question that he admires them all and shares their ideological point of view. Again, as someone who does not know this world very well, I am hesitant to comment, and as someone who counts a handful of the people mentioned in this piece as friends (including the piece’s author), I want to say emphatically here that nothing I say below has anything to do with my personal esteem for these people. I don’t become friends with someone because I agree with their take on politics or religion, and I certainly don’t cease to be friends with someone over that, unless the situation should become extreme. I have had people walk away from me over my religion and politics, but I make it a practice not to do that to other people. I wish I didn’t have to say that, but I wish a lot of things were different in this world.

Anyway, you can imagine the kind of people Brooks cites as the noble Evangelical pastors, professors, and intellectuals waging a valorous crusade to rid Evangelicalism of Trumpiness, a curse that includes resistance to a certain idea of racial justice and gender ideology. Now, if the idea is that large segments of Evangelical Christianity gave itself over to crazy Trump worship, and compromised their religious principles, you get no argument from me. (You might remember what I wrote about the Jericho March in late 2020.) But what rubs me the wrong way about articles like Brooks’s is the way he construes Evangelical goodness and Evangelical badness according to a clean dichotomy. The “good” Evangelicals are the ones who hate Trump, embrace “racial justice” (as defined by the politics of 2020), and support a more progressive understanding of gender. LGBT doesn’t come up in the piece, but it’s definitely part of the mix. I know that Brooks is LGBT-affirming; some years back, he asked me to explain why I, as a Christian, hold to traditional beliefs on the matter. I did not convince him of the rightness of my position, but he sincerely wanted to know, and I respect and appreciate that). LGBT issues are one line that many Evangelicals, however progressive their positions are in other areas, won’t cross.

From the article:

Russell Moore resigned from his leadership position in the Southern Baptist Convention last spring over the denomination’s resistance to addressing the racism and sexual abuse scandals in its ranks. He tells me that every day he has conversations with Christians who are losing their faith because of what they see in their churches. He made a haunting point last summer when I saw him speak in New York State at a conference at a Bruderhof community, which has roots in the Anabaptist tradition. “We now see young evangelicals walking away from evangelicalism not because they do not believe what the church teaches,” he said, “but because they believe that the church itself does not believe what the church teaches.”

The proximate cause of all this disruption is Trump. But that is not the deepest cause. Trump is merely the embodiment of many of the raw wounds that already existed in parts of the white evangelical world: misogyny, racism, racial obliviousness, celebrity worship, resentment and the willingness to sacrifice principle for power.

More:

[I]t’s not just normal bickering. What Mindy Belz notices is that there is now a common desire to pummel, shame and ostracize other Christians over disagreements. That suggests to me something more fundamental is going on than a fight over just Donald Trump.

Yes, for sure. The gaping hole in the Brooks analysis is that what’s happening in Evangelicalism is just a mirror of what’s happening in the broader culture. Believe me, the Christian Left, in its various iterations, has no problem desiring, pummeling, shaming, and ostracizing Christians who don’t share its views. It’s the same thing on the political and cultural Left — and on the Right. Granted, Christians are supposed to be better than that, but the idea that Church people are going to be untouched by conflicts raging in the outside world is naive.

Leaving aside the frothy, combative folk of Evangelical Left and Evangelical Right, we have to acknowledge that there really are substantive moral and theological issues here. For example, Brooks holds up several black pastors and Evangelical figures as embodying the correct Christian position on race and race relations. I wonder what he would make of Voddie Baucham, the black Southern Baptist pastor whose bestselling book Fault Lines gives a deep and persuasive popular critique of social justice movements and the danger they pose to Christianity. Baucham is no defender of racism, but he does talk about how the current conceptual framework of social justice actually runs counter to what Christians profess to be true. I read the book and found it to be quite powerful, but maybe Baucham (and I) are wrong about this. But even if so, is Voddie Baucham really the kind of Evangelical from whom Evangelicalism needs to be saved by more liberal Evangelical pastors? Where does Voddie Baucham fit into David Brooks’s analysis? I hope Brooks will read Baucham’s book and write about it in a future column.

Similarly, for Kristin Kobes Du Mez, another of Brooks’s heroes in the piece, the Evangelical church is threatened by toxic masculinity. I would imagine that she has something of a point. But I also know that there are Evangelicals, like my friend Denny Burk, a professor at Southern Theological Seminary, who believe profoundly that women are forbidden by the Bible from holding pastoral positions in churches. Denny has been publicly critical of Donald Trump too. But is Denny the kind of Evangelical from whom Evangelicalism needs saving?

In my own circles of Christians of all different churches, I know a fair number of theologically conservative people who would identify as Trump supporters, but not one of them thinks Donald Trump is a good man. They voted for Trump because they are frightened by the Left. All, or almost all, of them work in professional circles dominated by liberals and progressives, and they see every day what liberals and progressives believe, including about people like them. You will never see any of these people publicly praising Trump, or going to a MAGA rally, much less speaking of Trump in the frankly embarrassing ways of some popular Evangelicals, who see him as the Great Savior of Christianity. Their view of Trump is entirely realistic, in the sense that they know who he is, and they know who his opponents are, and they are less afraid of him than of his opponents.

If Trump had never descended the golden escalator on that day in 2015, would all be well with American Evangelicalism? I doubt it. All the churches now are roiled to some degree or another by the challenges of our post-Christian society. Evangelicalism is dealing with the fallout from revelations of sexual and other corruption among its leadership. Catholicism in America had to deal with that starting in 2002, long before Trump reinvented himself as a politician. In my own church, Orthodoxy, there are some liberals who want to queer the Church, and there are some conservatives who want to believe that if we just keep our heads down, LGBT questions will pass us by. There is no way to hide from this stuff. It will find you. The question is, what will you do when it does?

Again, if you want to get rid of the rabble rousers on both sides of these controversies, you will still have questions that cannot be easily resolved, if they can be resolved at all. Is Critical Race Theory and its offshoots legitimately Christian? Is it something about which Christians can disagree in good faith? Or is it something that strikes at the heart of the Gospel? What does Scripture and Tradition say about homosexuality, and genderqueerness? How should we understand those phenomena, and respond to them? What about the role of women in the institutional church?

What sticks in my craw is the seemingly unexamined assumption that if you don’t land where educated middle class elites do on any or all of these questions, that you must in some sense be a threat to the integrity of the Church. Perhaps educated middle class elite opinion is the real threat, you know?

Brooks’s column pairs well with Basham’s piece because they both seem to identify an Evangelicalism that valorizes being a certain kind of person, with a certain cast of mind, as giving one moral credibility. As a Catholic years ago, I saw this kind of thing all the time.

Case in point: Catholics like me were easily persuaded to accept the arguments of certain Catholic figures (clerical and lay) because they were on Our Side, and to dismiss the claims of others, because they were the Other. Case in point: the liberal Catholic journalist Jason Berry did fantastic work exposing the evil of Marcial Maciel, the deeply corrupt founder of the Legion of Christ religious order. The late Father Richard John Neuhaus fell victim to the blandishments of the Legion, because the Legion, being militantly conservative, were his kind of Catholics. Neuhaus denounced Berry and his colleague Jerry Renner for slandering good and holy Father Maciel and his movement. I remember wincing at that when I read it, because I know Berry somewhat, and though I didn’t agree with him theologically, I knew him to be a serious and honorable journalist. Yet I saw a lot of my Catholic friends took Neuhaus’s line, because they gave Neuhaus authority, and because they too believed that the Legion must surely be under assault by the wicked libs.

Of course we all found out after John Paul II passed that Berry was right, and Neuhaus was catastrophically wrong. I’m not getting on my high horse here: if it hadn’t been for my friendship with Jason Berry, and the cracks that my own reporting (not on the Legion) had put in my confidence in conservative Catholic leaders, I would have been right there with Neuhaus.

Basham’s piece challenges the idolization of Francis Collins by Evangelical elites, who in her view allowed the government to exploit that trust to use them. Brooks’s piece praises Evangelicals who challenge those Evangelicals who idolize Trump and MAGA-ness, but doesn’t dig into the core theological issues that exist whether or not one is an ideological brawler. In other words, these figures agree with David Brooks’s view of the world, so he trusts them, even thought it is possible that they are right about Trump, but wrong about other things.

I am thinking now of a man I came to know a bit a couple of decades ago, when I was writing about the Catholic abuse scandal. Steve Brady was a small-town Illinois Catholic who ran an outfit called Roman Catholic Faithful. Steve was a conservative, but he was not cosmopolitan, and not polished. What was he? Brave, and principled. He called out corrupt bishops — even those who had sympathies of conservatives — before it was cool to do so. I met him in person at the 2002 Dallas bishops’ conference meeting — the first one since the scandal broke nationwide. He was modest and unassuming. At that same meeting, I was asked by the freelance correspondent Fox News had hired to cover the event to give her a briefing. She was not a Catholic, and didn’t know who the players were, or what the issues were. When I got to the part about the role homosexuality played in the scandal, she shut me up and said that “we can’t go there.” She explained that there were orders from the top of the network to avoid talking about that. When I suggested that she should talk to people like Steve Brady and Michael S. Rose, she said sorry, she was told to stay away from people like that. This was Fox News, but it was manipulating the narrative as much as any liberal news network.

But Fox is respectable. Steve Brady? Just a small-town Catholic hothead, according to Team Roger Ailes. A nobody, best ignored.

What’s so hard about all this is that it is hard to separate the personal faults of individuals from the beliefs they hold. I genuinely hate the way so many people on my side demonize David French, a friend who is a decent man. Yet I also believe, just as genuinely, that French is wrong about some significant things. It ought to be possible for us to dispute these ideas without falling into personal invective, but very few people on either side these days seem to be capable of doing that. Me, I would like to see Evangelicalism shake free of the MAGA grifters, and those who believe somehow that the Republican Party is the vehicle of our temporal salvation. But I don’t see how things will be better off by trading one set of ideologues for another, even if I would rather have dinner with the right-liberals than with Jericho Marchers.

Francis Collins is an infinitely more respectable Christian public figure than any number of MAGA World luminaries, but it’s debatable as to who has done more damage to Christianity. I would say that if Evangelicalism needs to be “saved,” it’s might be as much from the Collinses, who lend respectability and authority to some repulsive ideas, as from the MAGAheads. What’s not debatable at all to my mind is that Viktor Orban, the Calvinist politician who leads Hungary, is a far better friend to Christianity than figures like Cardinal Hollerich of Luxembourg, the leading European Catholic bishop — and I know plenty of Catholics who would say the same thing. But none of them would be allowed to write that in The New York Times. The slick progressives holding power at senior levels within the Catholic institution are a far greater threat to its integrity than just about anybody else on the scene.

What this is all about, in the end, is the widespread collapse of authority within our culture — within the culture of the Church, and within culture, period. Nobody knows who to trust, or why. Hannah Arendt warned that the collapse of hierarchies, and the willingness of people to believe that “truth” was whatever those they already agreed with said it was, was a precursor to the coming of totalitarianism.

UPDATE: A reader suggested taking a look at the conservative commentator Erick Erickson’s take on this controversy. It’s worth reading.

Basically, Erickson thinks Basham’s piece was powerful, but after making some phone calls to people he knows at NIH, he comes away more sympathetic (but not entirely sympathetic) to Collins than he was after reading Basham’s piece.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.