The Saint, The Kite, And The End Of Culture

I want to take the liberty of republishing here the latest missive from the journalist David Rieff, a man of the Left who despises wokeness, taken from his Substack newsletter, titled Desire and Fate. I want you to subscribe to it — I think it’s free, but then, I would pay to read David anyway. I don’t think David’s views are those of his late father, Philip Rieff, but this beautiful, gloomy passage is worthy of Rieff père — which for me, is really saying something:

(With apologies to Christopher Caudwell – the British Marxist critic, not to be confused with the American conservative writer Christopher Caldwell):

Studies in a Dying Culture #1

Only 8% of university students in the UK are enrolled in humanities subjects. This is the context in which the culture wars are being contested: as Borges said of the Falklands/Malvinas War, it is a case of two bald men fighting over a comb. This does not mean the issues in dispute are unimportant. Far from it. The madness of Woke and the barbarous inanities of “anti-racism’ (please note the inverted commas!) are well on their way to destroying high culture in the Anglosphere and probably in parts of Latin America and Western as well, even if in those regions there is the kind of cultural pushback that has all but disappeared in the Anglosphere. This is because most of the Right in the US, Canada, and Australia is no more committed to high culture than it is the preservation of the environment, whereas as in Western Europe and Latin America high culture has not for a century at least been largely a monopoly of the Left, if not a monoculture, to use a phrase the critic Harold Rosenberg once used to describe Jewish intellectuals. In contrast, from Borges to Houellebecq a conservative tradition remains alive in Western Europe and Latin America, whereas in the Anglosphere, once one gets past Chesterton, Eliot, Flannery O’Connor, and Walker Percy, the cultural pickings are slim indeed.

For all that, though, in fifty years it is likely that these culture wars will seem like the last spasms of a fish flapping desperately in its last moments on the deck of a fishing trawler than it will the existential ideological and ethical conflict it so often appears to be today. Let us for once be honest: what is on offer in terms of contemporary culture on both sides of the Woke/anti-Woke battle line today is a penumbral shadow of the culture of the past. This is not to say that there are not people of talent in both camps. But if we are being rigorous, it is simply a fact to say that the greatest days of Western culture are behind it. There is nothing unusual in this. Cultures and civilizations are as mortal as human beings. The great Renaissance historical and politician Guicciardini says somewhere that a citizen must not mourn the decline of their city. All cities decline, he writes. If there is anything to mourn it is that it has been one’s unhappy fate to be born when one’s city is in decline.

A lover of high culture should nonetheless be clear-eyed about the quality of what is being produced today. At its best, it is good, not great. But a believer in the great Woke cultural revolution should be equally clear-eyed: the fantasy that culture can be largely representation of the historical unrepresented or that testimony is art is a consoling fiction. In some ways, the Woke fantasy is a kind of infernal mix of Blake and Mao Tse Tung: the cult of experience fused with the cult of cultural revolution. At its worst, Woke culture is just Western fantasies about the authenticity and nobility of the tribal and the premodern, this in a time when racial identity has never been more in flux, and the intermingling of the races more and more the norm (look at who American Jews and Japanese-Americans marry for the extreme end of this). For “my race/people my spirit will speak,” wrote the great Mexican thinker José Vasconcelos (it is hard to convey the exact meaning in English of the Spanish word “raza”). But the Woke and the “anti-racist” are tying themselves to the mast of an essentialist understanding of identity just as it is vanishing into air.

If there is a new culture waiting to be born, it will not be born of Woke and “anti-racism,” of Neo-Tribalist nostalgia, and notions of race that, typologically though of course not hierarchically, would have pleased the worst early 20th century White Supremacist scientist. But nor will Western high culture ever ascend to the heights that so many times, and so gloriously, it reached in the period between the Renaissance and the middle of the 20th century. That race has run its course. And the point is that somewhere, deep down, everyone knows this. Given that, why in God’s name would one want to study a subject in the humanities. There are, of course, material reasons for the death of the humanities as well. But one must be materialist, but not too materialist here – allegro ma non troppo, as it were. The old culture is dying, and what purports to be its successor has come into the world stillborn.

As important as it generally is to vote conservative, we are not going to vote ourselves out of this crisis. The core of it is cultural. Do you see American conservatives producing a vital culture today? The progressives have all the cultural energy, but are creating what Philip Rieff called “deathworks” (defined by Carl Trueman as “the act of using the sacred symbols of a previous era in order to subvert, and then destroy, their original significance and purpose.”) Their cultural works are parasitical on the creations of a living culture. They mostly destroy that which gives life.

Do you see why I’m so committed to the Benedict Option concept? The West is dying … and if Christianity is not going to die with it, we Christians have to take radical action to create resilient ways of living, in the same way that the early medieval Benedictines did.

Anyway, subscribe to Desire and Fate — I think this link will allow you to do so.

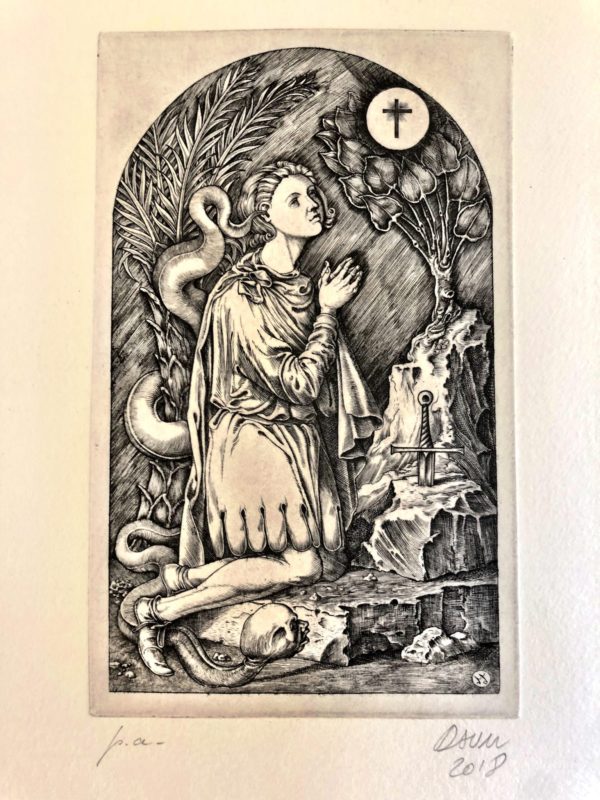

The deeper I get into my current book project, the greater the significance I give to this incredible engraving by the Genoese artist Luca Daum, who, as regular readers will recall, gave it to me after my 2018 talk in Genoa. He approached me and told me in broken English that he had been praying in his studio that afternoon when the Holy Spirit told him to go hear the American speak, and give him this engraving:

It’s titled “The Temptation of St. Galgano”. I won’t go into all the details again — you regular readers know this story — but in brief for those who are new to it, Galgano Guidotti was a 12th century Tuscan who was passionate and violent. His mother prayed for him to return to God. He had a miraculous vision one day while out riding his horse. A voice told him to put down his sword — a symbol of his disordered passion — and leave the world to serve God. Galgano told the voice it would be easier for him to plunge his sword into the nearby rock than to do what the voice asked. So he brought the blade down on the rock — and it went in. He was instantly converted, and became quickly known as a holy man. When he died, bishops and abbots came to his funeral. The Vatican still has the written documents from the investigation into his cause for sainthood, which got underway soon after his death. The cardinal who investigated it was able to speak to many people who knew Galgano, including his own mother, who testified to the reality of the miracle. He was canonized in the 1180s.

You can still see the sword in the stone, inside the church the local bishop built over the rock after Galgano’s death. It is protected by thick plexiglass. In the year 2000, Italian scientists investigated the phenomenon, and could not explain it. From The Guardian:

Galgano Guidotti, a noble from Chiusdano, near Siena, allegedly split the stone with his sword in 1180 after renouncing war to become a hermit. For centuries the sword was assumed to be a fake. but research revealed last week has dated its metal to the twelfth century.

Only the hilt, wooden grip and a few inches of the 3ft blade poke from the hill, which still draws pilgrims and tourists to the ruins of the chapel built around it.

‘Dating metal is a very difficult task, but we can say that the composition of the metal and the style are compatible with the era of the legend,’ said Luigi Garlaschelli, of the University of Pavia. ‘We have succeeded in refuting those who maintain that it is a recent fake.’

Ground-penetrating radar analysis revealed that beneath the sword there is a cavity, 2m by 1m, which is thought to be a burial recess, possibly containing the knight’s body. ‘To know more we have to excavate,’ said Garlaschelli, whose findings have been published in Focus magazine.

Carbon-dating confirmed that two mummified hands in the same chapel at Montesiepi were also from the twelfth century. Legend has it that anyone who tried to remove the sword had their arms ripped out.

In English legend the sword Excalibur is pulled from a stone by the future King Arthur, heralding his glory. In Galgano’s case the miracle signified humility and holiness.

What is Galgano’s temptation in Luca Daum’s drawing? To take his eyes off of God and look down to the ground. The seed he planted in rocky soil — the sacrifice symbolized by his sword — produced abundance (the tree atop the mountain). The image of the Eucharist in the tree branches is a sign of God’s veiled but Real presence, like the sun in the sky. This iconic image tells us that to sacrifice for God — to submit one’s will to higher things — is a precursor to fruitfulness. The temptation is a serpent with a human face, trying to convince the saint to take his eyes off of God and look at Man, crawling around in the rocky soil. But that would mean spiritual death.

Note well that this image does not advocate for a pristine, bloodless spirituality. The fruits of Galgano’s sacrifice — of allowing the holy to light his world and show him the way — are made manifest in the material world. Galgano renounced the world in a way very few are called to do. But all of us are called to subordinate our selves to God and His will. If we do that, we live by the Tao, and fulfill our telos. If not? Well, look around you.

Luca Daum is retelling the story of the Fall here — a story that is ever-relevant. I want you to think about the engraved image in light of what David Rieff writes. David is not a religious man, but you don’t have to be religious to interpret this image in a purely cultural way. Western culture today is built not on Christian faith, but on enthroning Man and his passions. We have cut the lifeline to the transcendent, and are dying on the vine. The point is obviously not that being a religious believer is sufficient to being an artist and culture-creator; religious kitsch proves that is untrue. Nor is that point that we lived in Eden when our civilization was Christian, but rather that our felt connection to the transcendent world gave us meaning and fed us with spiritual energy that allowed us to create. We could only see our immanent world as it is through the light provided by the Transcendent.

In Warsaw a couple of years ago, a Polish historian told me that our culture is like a kite: if it is bound to the ground with a tense string, the kite can soar high, but if the string is cut, the kite will not be free to keep ascending, but will fall to earth. This is a metaphor for our time. We refuse grounding in the Holy, and find ourselves living on our bellies, on hard rock.

UPDATE: The Dante translator Andrew Frisardi writes:

Purgatorio is a story of redemption through a change of heart that leads to confession, renunciation, and contrition. The characters Dante encounters in it are souls of people who had opened their hearts to the spirit, to God, before they died – even just before they died – and who are therefore free from the self-obsessed, desecrating, and egocentric perspective of Hell.

Yes, exactly. Without God, we worship ourselves, and eventually create Hell.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.