Church, Academia, Diversity

I received the following e-mail from a reader, who gives me permission to post it as long as I don’t disclose his identity. I have slightly edited this to protect him:

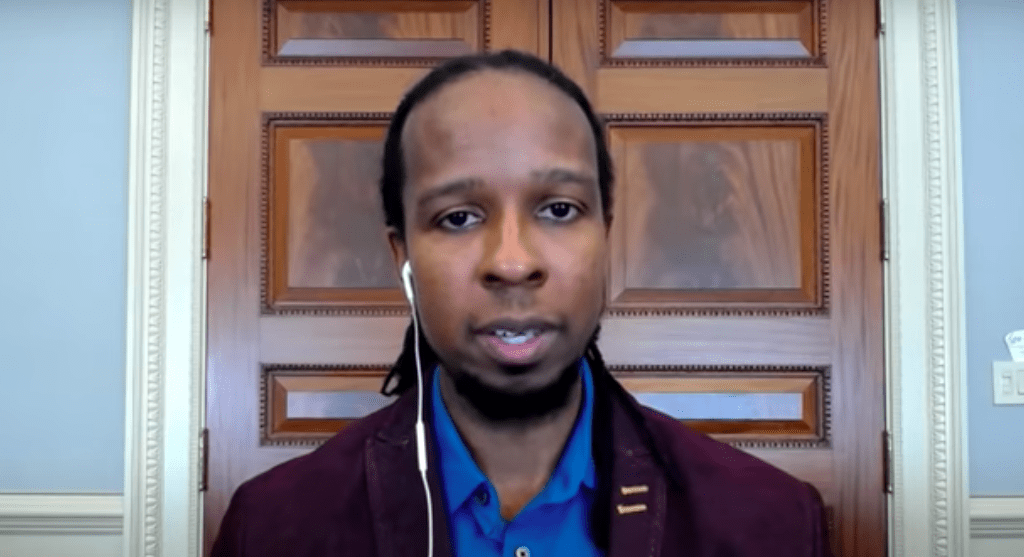

I have read your recent posts about race relations with interest and thought you might be interested in my efforts to have my church expand its dialogue about race to include viewpoints other than the “anti-racist” position advocated by people such as Ibram Kendi.

The reader then told me his religious and professional background. He is a white liberal who attends a liberal Protestant church in a major US city, and has been active for decades in work that is part of the civil rights movement. He goes on:

About a decade ago I began to realize that the civil rights movement was being hijacked by a very different approach to race relations and racial justice, which I will simply call the “anti-racist” movement. Colleagues at work and friends at church began to mock the idea of a color-blind society and argued that society must focus on racial identity as a means of achieving “racial equity.” I found it difficult to engage in meaningful dialogue with them. I sometimes think that the only reason they did not brand me as a racist is because I had worked my entire career fighting racial discrimination.

About two years ago my church did embark on a congregation wide discussion of “racial righteousness and equity.” It soon became clear that the only views that were going to be represented were of the anti-racist orthodoxy and, amazingly to me, most of the small group discussions were racially segregated. Recently, we have had a series of sermons (virtual of course) which have espoused the Kendi model and we have even had segregated prayers, where the white senior pastor prays on behalf of the white people and the black executive pastor prays on behalf of the African-American congregants. I was stunned at how far my church had come from MLK’s vision of an integrated society.

In February of this year, I emailed the senior pastor and executive pastor and asked them to expand the dialogue to include differing viewpoints. I sent them an essay I had written on my view of civil rights and the gospel — in order to give them an example of a different approach to achieving better race relations and advancing justice. Both pastors said they were too busy to engage with me and referred me to our church moderator (the lay leader of our church board). The moderator suggested that I read Kendi’s book “How to be an Antiracist” and that he would read John McWhorter’s book “Winning the Race” and that we would then discuss the two books. I agreed and enlisted a friend in the congregation who shared many of my views on the topic to read both books and join the discussion. The moderator enlisted two other members of the congregation to join in as well.

Reading Kendi’s book was eye-opening and disheartening. Things were even worse than I had thought. In my view, Kendi espouses racial separatism and demands racial “equity”, which he defines as equal outcomes in every aspect of life. [Kendi’s critics have pointed out that unequal outcomes are an inevitable result of a free and capitalist society and accuse Kendi of being a totalitarian.] Moreover, his approach is polarizing and highly judgmental. Perhaps the most dangerous aspect is his claim that moral suasion is useless and that antiracism is all about power. His book is so dogmatic that he rewrites history in an effort to bolster his views. For example, he claims that America only passed civil rights legislation in order to curry favor with newly independent African nations so as to keep them out of the Soviet orbit and that morality played no role in the civil rights movement of the Sixties. Also, he argues that Martin Luther King advocated segregated schools so that black children would not be harmed by white teachers. Both of these claims are demonstrably false. I wrote a critique of the book and sent it to the moderator and other participants in the discussion. My friend who thinks like me also wrote a critique of the book and sent it to the same people.

So I was looking forward to finding out why our church moderator liked the book. But the discussion has not taken place, mostly due to the killing of George Floyd and its aftermath. I am hopeful that we will have the discussion in the next few months because I genuinely want to find out what my fellow church members are thinking. I have tried to dialogue with individuals in the church, but I have not found anyone who wants to take the time to actually discuss the complex issues of race and justice, other than the few members who question the antiracist paradigm.

Our church discussion of race continues to be exclusively based on antiracist dogma. The books that have been discussed recently are “White Fragility” and “Me and White Supremacy.” Several months ago, I sent our senior pastor a link to John McWhorter’s article which argued that antiracism had become a new religion for some. She responded by saying that the article was “interesting” — but over the past several months my church seems to have actually imbibed that new religion!

The members of my congregation are sincere Christians who want to live out the gospel. They oppose police brutality and seek to fight racial prejudice and discrimination. We have a common goal. But we have very different ideas on how to achieve that goal. The leaders and movements that my church friends trust tell them that the only way to achieve the goal is to ally with the antiracism movement. I am still trying to find ways to have meaningful conversations with both black and white church members where we can explore the foundations of our viewpoints and seek common ground.

I am a liberal and we would likely disagree on many important issues. But I decided that I would not support antiracist orthodoxy simply because most liberals do. It has been frustrating to learn that nearly all of my liberal friends refuse to question the orthodoxy. I am actually glad that Kendi’s book has been near the top of the best seller list for several weeks. My hope is that enough people will actually read it and realize that it is a dangerous book which advocates ideas and methods which run counter to racial equality and stand in the way of improved race relations. I appreciate the fact that you have been advocating the traditional civil rights message of MLK and others and pointing out the flaws in the antiracist dogma.

Another reader — an Evangelical that I met in my travels — writes to tell me that he is leaving academia. He teaches at a Christian university:

Your recent posts inspired me to reach out to you. I’d like to explain my own intention to leave higher education entirely. If you think readers will find it interesting, you are welcome to share it (but please keep my identity hidden).

Over the last 10 years, our university’s traditional undergraduate enrollment shrunk by more than a third. Administrators attempted to remedy the crisis in ways that were entirely predictable. They brought in consultants; they marketed the university as an ideal destination for any career-minded person; they highlighted professional programs and portrayed their Christian identity in anodyne terms. Trustees—most of whom have no skin in the game when making university-related decisions—responded to budget shortfalls by calling for program eliminations. During this time, the university relied on athletic programs to drive enrollment.

At the end of the day, the university became a less compelling option for prospective students. The teaching environment also changed. The theological literacy of students deteriorated as the university marketed themselves to a wider demographic. While we managed to attract some good students, many (especially male athletes) were unprepared for college-level work. Retention became a responsibility for every professor. Yet enrollments still lagged, and more academic programs were eliminated, including my own.

The prospect of redefining my professional life is frightening, but staying in academia has no appeal for me. I’ve spent too much emotional energy defending the humanities only to see them subsumed by the servile arts. In cash poor colleges especially, humanities programs have only a nominal role in the curriculum. Administrators may acknowledge the inherent worth of the humanities; yet their survival requires demonstrating their value in economic terms.

For many years, I thought the Christian university could serve as a bulwark against secular drift. But its failure is assured by academia’s de facto objective. Frank Donaghue, a professor of literature at Ohio State, is precisely right: “Higher education is job training, however academics like to think otherwise” (The Last Professors, 85). In this regard, Christian universities are no different than their secular counterparts. Despite their professed mission, they are almost entirely utilitarian in their perspective and bourgeois in their aims. In some cases they can’t afford not to discard the disciplines that would help the Church think carefully and responsibly about the world and its place within it. There are exceptions to this trend, of course. But on the whole, Christian education is increasingly incapable of addressing present day cultural challenges in bold and effective ways.This became especially clear to me in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. I watched several Christian college presidents attempt to establish their anti-racist credentials through feckless moral posturing. As far as I know, none will admit to using academically underprepared young men (many of whom are racial minorities) to pad their enrollments.

Yes, administrators will continue reminding constituents about their institutions’ “enduring Christian mission” and “transformative” educational experience. Such language is an adornment masking the smell of polluted air. Scroll through the list of member colleges and universities of the CCCU. Many of them are bullshit centers of cultural assimilation and vocational training. As crushing student debt increases, these universities will have a harder time explaining why someone should pay more tuition at an institution which may not exist in five years.

Worries about my own career aside, there is something liberating about being untethered from an institution whose future is less than promising.

Here’s a different voice. A Christian academic friend forwarded me this e-mail from a correspondent, who gave me permission to post it as long as I didn’t identify him:

I think both [David French and Rod Dreher] significantly overstate the risks that Christians experience in the public sphere and in academia, in particular; I think their entrenchment in the class of social commentators who spend a lot of time *online* has inhibited their ability to reliably assess the dangers. Rod, in particular, is prone to giving too much weight to the anecdotes told by his readership and the loud voices on Twitter and blogs.I am a [scientist] at [well-known university], a bastion for progressive social activism. Perhaps my experience is inconsistent with the experiences of academics in the social sciences, humanities, and arts; but here is my own anecdote, such that it is: nearly everyone with whom I closely work knows that I am an evangelical Christian, and I have felt only the slightest “persecution,” and I’m unsure if that is the most accurate term for those rare experiences. I have shared the gospel with my boss (an atheist assistant professor who was raised Muslim by [immigrant] parents in the States) and other colleagues in my lab; it’s not as if I am quiet about my beliefs. I wear t-shirts with my church’s logo and host lab parties at my home, where Bible verses are and Bibles are conspicuous. This isn’t to say I think those icons are effective evangelistic tools, only that my faith is far from hidden.It’s also not as if I am insulated from the sort of people whom Rod and David would imagine are likely to be intolerant of me. A PhD student in my lab checks all the boxes: atheist/pagan, raised in southern California with some Mormon influences, married to the angry son of hyperconservative Christians, sister to a trans brother, vegan, animal rights activist, and vociferously pro-choice. She has twice worn a shirt to lab that says “THANK GOD FOR ABORTION” that nearly made me vomit. Earlier this year a rumor that I didn’t “believe in evolution” swept through my lab. It caused a little stir, especially for this PhD student, who was worried that this belief would interfere with my work and hence our ability to work together. The rumor was false, and it took several months (and a night at the pub) for her to divulge the rumor to me, which I immediately corrected.The next morning, we debriefed our conversation. I told her, “Indeed I believe in evolution. But I want to be clear, and I want you to understand, that I believe some things that you would find absolutely wacky. I believe a dead man came back to life.” She considered it for a moment and replied, “That’s fine, as long as it doesn’t interfere with your work.”In the past, we had a research specialist who was gay and an integral member of the LGBTQ+ community in [our super-progressive town] and at the university. One day in the office, I experienced a bit of discomfort when a moderately famous professor in our department made a joke about how a church is that last place you’d expect to see a scientist. After she left, I turned to my gay colleague and said, “I was pretty uncomfortable during that interaction, as the professor made clear that she did not see science and church attendance as compatible. I know that you have experienced from people like me far worse discrimination, and I want you to know that if I ever make you feel like that, please inform me.”He replied, “That means a lot to me. And please do the same if I repeat her mistake.” We never entered into a political discussion of whether gay marriage should be legal, or what I thought about the interactions between the church and public LGBTQ+ activism. Those things didn’t matter; what mattered was a collegial, mutual compassion and respect for each other.In [our town], it’s common for churches and Christians to act as if they are always under attack.Sure, every once in a while there is a hit piece in the newspaper about whether or not a church is LGBTQ+ affirming, but my experience is that the persecution is overstated. One of the problems with Christian defensiveness is that it negates the much more offensive (and by that I mean forward-moving, as a soccer team goes from a defensive posture to an offensive one after re-taking possession) act of love. Love is not advanced from a defensive posture, so I am often inclined to think that Christians who are on the defensive are so because they have neglected the Christ-commanded advance of love. This obviously isn’t always the case in world history; there are indeed plenty of offensively loving Christian groups that have nevertheless experienced extreme persecution, as the Bible predicts and promises. Only in rare cases does this sort of persecution occur in the United States.To sum up: I live in a city that historically has been conceptualized as being hostile to Christians. [My town] is known as “the city where churches go to die.” I am in a less than secure career situation yet have been vocally Christian among people whom Rod and David would not guess to be tolerant of an orthodox Christianity. My love and compassion for them is as perceptible and offensive as my Christian beliefs. I have never been in any danger of losing my job or of losing social status or respect in my lab. It is possible that my experience is not the norm. Make of that what you will.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.