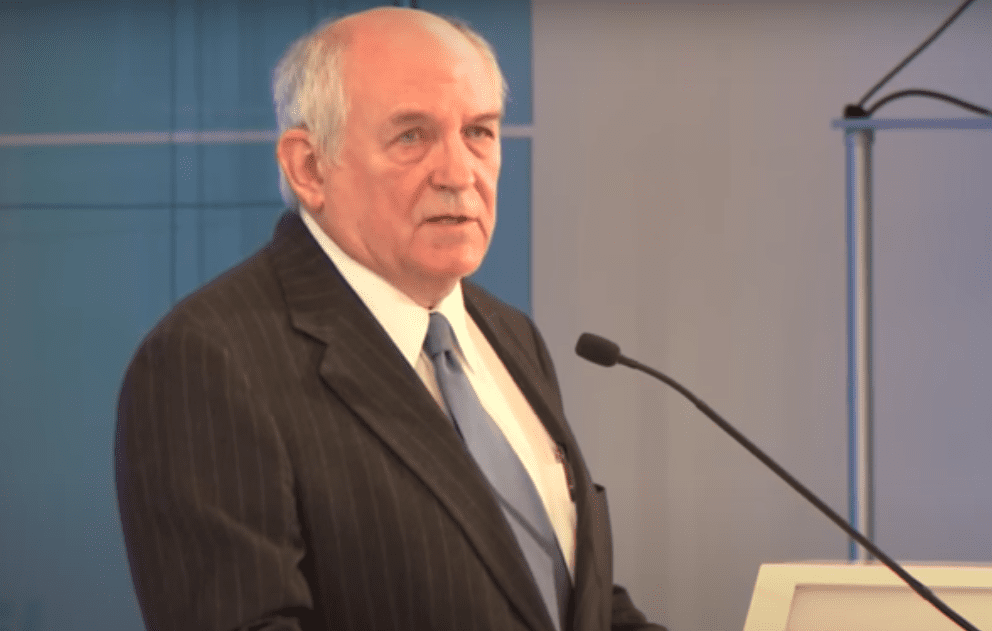

Charles Murray: God Is America’s Only Hope

“The Founders were not really super orthodox,” he observed. “They were all nominally Christians, but they wouldn’t pass the litmus test for a lot of evangelicals today. But they were absolutely, emphatically agreed that you cannot have a free society with a constitution such as the one they had created unless you are trying to govern a religious people. If you do not have religion as the controlling force, then the kinds of laws we have could not possibly work.” Without religion, Murray told me, there was simply no “intrinsic motivation” for people to behave morally — and no definition for what constitutes moral behavior in the first place.

The current experiment that the West has embarked on, in Murray’s view, has an expiration date: “I cannot believe that the secularization of society is going to continue indefinitely. We have never had an advanced culture, in the history of the world, that is as secular as contemporary Europe. I would say that it is the test case, the canary in the coalmine. And so Sam Harris, who I like and respect, will say that as a secular humanist society, they’ll do just fine and they’ll do just fine over the long term. My own sense is [that they won’t.] You cannot have a free society, a society that allows lots of individual autonomy, without some outside force that leads people to control the self. And I think the increasing Muslim minorities in those countries are probably going to accelerate the exposure of the degeneracy.”

Murray says that American exceptionalism is now meaningless, that the US is a country

“… where [our] ideals are basically, we’re gonna be a rich, powerful country and you’ll still have Americans say USA, USA at sports events and so forth. But to the sense of the American Way of Life, which was something that was in common use until fifty years ago, well, it will be meaningless or already is meaningless.”

Murray says that the solution is to do as he has done, and move out to live in a small town

which is run just as Alexis de Tocqueville described in the 1830s. There are all sorts of places like that around. It’s really easy to live in traditional America, and that’s true no matter what your ethnicity is, no matter what your economic status is.

I wish that were true, but it’s not. Maybe it’s true for Murray’s town, I dunno, but the idea that it’s “really easy to live in traditional America” is romantic nonsense. I’m surprised that someone of Murray’s intelligence can believe that. Murray lives in Burkittsville, Maryland, pop. 151. I’m sure it’s a great place with lovely people, but how on earth can you say that “it’s really easy to live in traditional America” based on your experience of your rural town of 151 people?

Does Murray not realize that television and the Internet have reached all corners of America? I come from a great small town, one that’s in a conservative part of America. I wrote a book about its virtues. But let’s be honest: kids there are watching porn on their smartphones too, and the advance guard of the Sexual Revolution has arrived even there (gay couples attend middle school dances). As someone who has lived in small towns, medium-sized cities, and big cities, I have found no Mayberry anywhere to which people can retreat. What made (and makes) my hometown such a wonderful place, as revealed in the story of my sister’s cancer, was not its smallness, but the powerful sense of community there. You could have that in a big city too, under certain circumstances.

Why, I wonder, does Murray think that small town life protects people from ceasing to believe in God? It might have done so to a certain extent when I was a kid, in the 1970s. Even people who didn’t go to church, or go to church that often (like my family), still professed belief in God. We only ever heard the word “atheist” when one of the networks would do a piece on Madalyn Murray O’Hair. But today? Look, half a century ago, there wasn’t any real social penalty to be paid in my town for not going to church, though nobody would have ever called themselves an atheist. There is still no social penalty for not being a member of a church, and no one would stand on the street corner and brag about being an atheist, but if someone said they didn’t believe in God, it wouldn’t be a scandal.

To be clear, I’m not saying this as a criticism of my hometown, or of small towns. I’m a booster of small towns! I live in the city now, but if our little church had been able to make it there, I’d still be living in that small town. I’m just trying to inject a note of realism here. Small-town people are just as caught up in modernity as the rest of us. Back in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when my wife and I lived in New York City, it was a running joke with us on the plane back home after holiday visits that it was nice to be getting back to Brooklyn, where everybody lives nice, clean, bourgeois lives. We would have caught up on all the juicy small town gossip while visiting down in Louisiana, you see. The joke was that of course all this and more was going on behind the nice brownstone façades of our neighborhood, but it was a lot easier to remain ignorant of it in a big city than in a small town.

It’s also the case that a lot of small town in “traditional America” — though happily, not my own hometown — are really suffering from economic and social breakdown. Take a drive up through the Mississippi Delta in northern Louisiana, as I did a few years back for my kinsman’s funeral. Country towns that had once been thriving under agricultural economies are now ghost towns. It was a real shock to me, seeing that; I realized that if I had come from a town like one of them, there would have been nothing to return to. We all know too about how the scourges of opioids and meth have hollowed out a lot of small towns. Despair is not bound by geography. People who want to leave the cities to live in small towns might genuinely have a calling, but they should be as realistic as possible about it, and not assume that in so doing, they are escaping back to a Tocquevillian utopia.

Of course I agree completely with Murray that the country will not hold together absent religion. Philip Rieff — who, like Murray, was an agnostic — believed the same thing. Rieff was a sociologist and a sophisticated social critic. His argument was that without a reference point in transcendence — and not transcendence as a lofty abstraction, but as something felt to be a real reality — that society cannot do what society’s must do to survive. I’m not going to go into all that again here — if you’ve read this blog for a while, you know the argument. Rieff’s contention is not theological, but sociological and psychological.

The problem, though — and Murray no doubt groks this — is that you can’t force yourself to believe in God because it’s good for you, and for society. What Murray tells Van Maren is simply a restatement of John Adams’s famous line: “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.” Adams meant that liberal democracy works because people have learned how to govern themselves personally, having internalized the moral values of religion. They can be trusted with liberty not because they are saints, but because they know how to order that liberty in their personal lives.

The usual objection at this point is, “So you don’t think atheists can be moral?” It’s obvious that some atheists behave with more exemplary Christian morality than do many Christians. That is beside the point entirely. The more serious question is, “How does an atheist determine what is moral?” On this point, see Nietzsche.

Besides, the more or less post-Christian countries of Scandinavia live peaceful, orderly lives, despite having little or no religion. We’ll see how long that lasts. The habits that came into being in large part through Christianity may fade in time. I recall a visit around 1990 I made to visit a friend in a tiny Dutch farming village near the German border. My friend’s father had been a Catholic seminarian in youth, but left to marry. He spoke no English, but my understanding, via his daughter, my friend, was that he was sorrowful over the collapse of Catholicism in their country. At breakfast on my last morning there, before my friend left for work, she told me that a farmer friend of her dad’s had committed suicide the previous night.

The father couldn’t communicate this to me. As he drove me to the train station, we passed by beautiful farmhouses, set in pastures of emerald green. It was the most serene, orderly scene imaginable. But as we drove down the country road, the older man pointed to various houses, and said simply, “Suicide. Suicide. Suicide.” He was telling me about all his neighbors who had killed themselves. Why? They lived in a peaceful, prosperous, orderly middle class nation. And yet, they had found life to be not worth living. This is a very serious problem, and not one that can be settled by pointing to the GDP, the crime statistics, and other measures of material progress.

Anyway, read all of JVM’s interview with Murray. As you know, especially if you’ve read The Benedict Option, I believe it’s going to get much worse before it gets better. The greatest task facing Christians in post-Christian America is to establish ways of life that allow us to endure this new Dark Age, and that ultimately show the country the way back to God, when people decide they want Him again.