Big Journalism Embraces Propaganda Model

You will have seen that Americans have sharply declining trust in the media. For example, results of this April poll:

The headline of that graphic is not quite accurate. Even Democrats’ trust has significantly declined.

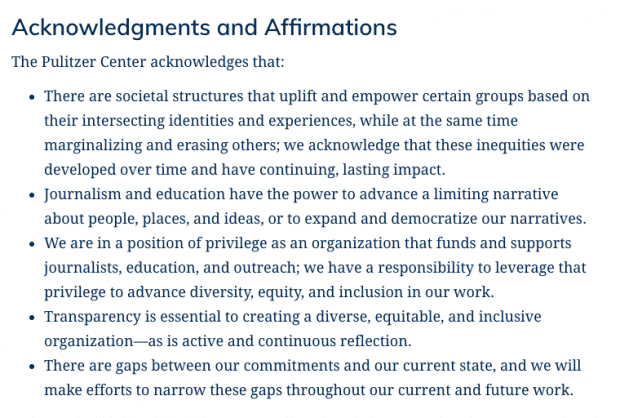

If people believe that the media are not playing it straight, trying to be fair, I would direct them to this statement on “diversity, equity, and inclusion” by the Pulitzer Center, which administers the Pulitzer Prizes [UPDATE: I was wrong; the Pulitzer Center does not administer the Pulitzer Prizes — Columbia University does. I apologize for the error — RD]. This is a big deal. It represents the abdication of professional journalism standards, and the adoption of those of a left-wing propagandist. Excerpt:

This is what it sounds like when progressive ideologues in journalism use jargon to talk themselves into embracing left-wing propaganda strategies as a virtue. I remind you that the Pulitzer Prize committee this year awarded the Pulitzer Prize in Commentary to Nikole Hannah-Jones for her role in The 1619 Project, the big New York Times attempt to rewrite the history of the American founding to make it ideologically useful in advancing progressive identity politics.

I remember around 2004, having a conversation with a fellow conservative journalist, about how frustrating it was to deal with young conservatives who contacted us wanting advice about going into journalism as a career. Believe me, if you are a conservative working in the mainstream media, you dearly want to encourage as many conservatives as you can to join the profession, to help correct its many biases. The problem with those aspiring young people, my conservative colleague and I agreed, is that so few of them actually wanted to learn the craft of journalism. They wanted to become journalists as a form of political activism. This is exactly the wrong reason to go into journalism, we thought. So many of the problems of American journalism stem from crusading reporters being more interested in advancing progressive narratives than in telling the complicated truth about life. But at least the liberals, whatever their faults, usually respected the craft enough to learn how to do it well.

Now? I could not in good conscience advise young conservatives to go into journalism, at least not of the mainstream kind. I don’t believe the culture of newsrooms today is reformable. I could be wrong! I haven’t worked in a newsroom for eleven years. But I read and listen to the media all the time, and the kind of biases I routinely saw have gotten worse. Now you have the Pulitzer Center openly abandoning fairness in favor of “expand[ing] and democratiz[ing] our narratives” — Orwellian prog-speak that tells you exactly the kinds of stories they are committing to tell, and the kinds that they will not tell. Some people are more diverse than others, you know.

There is a kind of conservative who thinks that if they just keep pointing out to newsroom leaders the deep inherent biases in their coverage, that the institutions will reform. Does anybody believe that now? Donald Trump may have exploited the mistrust many conservatives have of mainstream journalism, but this wasn’t invented by Trump. Professional journalists are among the least self-aware people around. I remember being at a big national journalism conference back in the 2000s, drinking at the bar with the handful of conservatives in the room, all of us telling stories about the total blindness and bigotry we’ve seen. I’ll tell you, if you have been a minority in a professional space, as conservatives (especially religious conservatives) are in professional journalism, you learn first-hand that there is truth in the oft-heard claim that diversity is important in newsrooms, because it has to do with the kinds of stories we tell. You also learn, though, that most people in journalism see “diversity” as going only one way.

Here’s a 2019 piece I discovered recently by Amanda Ripley, about how journalism can tell stories better. You might think it’s a thumb-sucker of a piece, but it’s actually good, even for non-journalists. She writes about how the standard model of conflict-driven journalism actually does not offer an accurate picture of society’s divisions. Ripley ended up interviewing people who are involved in professional conflict-resolution, and tries to apply the lessons she learns to the journalism craft. Excerpts:

I’m embarrassed to admit this, but I’ve been a journalist for over 20 years, writing books and articles for Time, the Atlantic, the Wall Street Journal and all kinds of places, and I did not know these lessons. After spending more than 50 hours in training for various forms of dispute resolution, I realized that I’ve overestimated my ability to quickly understand what drives people to do what they do. I have overvalued reasoning in myself and others and undervalued pride, fear and the need to belong. I’ve been operating like an economist, in other words — an economist from the 1960s.

For decades, economists assumed that human beings were reasonable actors, operating in a rational world. When people made mistakes in free markets, rational behavior would, it was assumed, generally prevail. Then, in the 1970s, psychologists like Daniel Kahneman began to challenge those assumptions. Their experiments showed that humans are subject to all manner of biases and illusions.

More:

Researchers have a name for the kind of divide America is currently experiencing. They call this an “intractable conflict,” as social psychologist Peter T. Coleman describes in his book The Five Percent, and it’s very similar to the kind of wicked feuds that emerge in about one out of every 20 conflicts worldwide. In this dynamic, people’s encounters with the other tribe (political, religious, ethnic, racial or otherwise) become more and more charged. And the brain behaves differently in charged interactions. It’s impossible to feel curious, for example, while also feeling threatened.

In this hypervigilant state, we feel an involuntary need to defend our side and attack the other. That anxiety renders us immune to new information. In other words: no amount of investigative reporting or leaked documents will change our mind, no matter what.

Intractable conflicts feed upon themselves. The more we try to stop the conflict, the worse it gets. These feuds “seem to have a power of their own that is inexplicable and total, driving people and groups to act in ways that go against their best interests and sow the seeds of their ruin,” Coleman writes. “We often think we understand these conflicts and can choose how to react to them, that we have options. We are usually mistaken, however.”

Once we get drawn in, the conflict takes control. Complexity collapses, and the us-versus-them narrative sucks the oxygen from the room. “Over time, people grow increasingly certain of the obvious rightness of their views and increasingly baffled by what seems like unreasonable, malicious, extreme or crazy beliefs and actions of others,” according to training literature from Resetting the Table, an organization that helps people talk across profound differences in the Middle East and the U.S.

Ripley concludes:

The lesson for journalists (or anyone) working amidst intractable conflict: complicate the narrative. First, complexity leads to a fuller, more accurate story. Secondly, it boosts the odds that your work will matter — particularly if it is about a polarizing issue. When people encounter complexity, they become more curious and less closed off to new information. They listen, in other words.

There are many ways to complicate the narrative, as described in detail under the six strategies below. But the main idea is to feature nuance, contradiction and ambiguity wherever you can find it. This does not mean calling advocates for both sides and quoting both; that is simplicity, and it usually backfires in the midst of conflict. “Just providing the other side will only move people further away,” Coleman says. Nor does it mean creating a moral equivalence between neo-Nazis and their opponents. That is just simplicity in a cheap suit. Complicating the narrative means finding and including the details that don’t fit the narrative — on purpose.

The idea is to revive complexity in a time of false simplicity. “The problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue but that they are incomplete,” novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie says in her mesmerizing TED Talk “A Single Story.” “[I]t’s impossible to engage properly with a place or a person without engaging with all of the stories of that place and that person.”

I’ll share with you a good example of this. Not too long ago, This American Life featured a story by B.A. Parker, a young black woman who began by talking about how much it bothered her that white tourists (usually Europeans) would come to her black urban church on Sundays for a “gospel experience.” I thought it would be the usual formulaic public radio griping about Racism. As Parker went on, though, I began to sympathize with her. Wouldn’t you be frustrated as a Christian worshiper if people started showing up at your church for the cultural experience of Christian exotica? I would. But it became clear that Parker had become so stuck on thinking about the white tourists watching her and her fellow congregants that it was interfering with her ability to experience God in church.

Then Parker interviewed her pastor about her anger over all this. The pastor was pretty wise, saying, basically, that nobody can really know what’s going on in the hearts and minds of a person who comes to church, and for all they know, at least some of those tourists might leave genuinely wondering about the source of the worshipers’ joy. And that might be the first step on the road for conversion for them. The pastor responded with tolerance and mercy — a tolerance and mercy that challenged my own views, which, by the time the pastor was interviewed, had solidified around Parker’s opinion.

Anyway, this piece was a first-rate example of storytelling that complexified the issue, and compelled listeners to engage with what was being said, instead of reflexively taking sides. What I expected to be a simplistic public radio piece about White People Being Bad turned out to be a nuanced exploration of Christian worship, identity, and the challenges of Christian witness across difficult racial and cultural boundaries. The story was so good because B.A. Parker was willing to interrogate herself, and her own biases — and to highlight in her radio essay the voice of her pastor, who challenged her.

Contrast that with the by-now infamous transcript of the New York Times‘s internal town hall meeting about race and its coverage, in which an unidentified staffer said this to executive editor Dean Baquet:

I’m wondering to what extent you think that the fact of racism and white supremacy being sort of the foundation of this country should play into our reporting. Just because it feels to me like it should be a starting point, you know? Like these conversations about what is racist, what isn’t racist. I just feel like racism is in everything. It should be considered in our science reporting, in our culture reporting, in our national reporting. And so, to me, it’s less about the individual instances of racism, and sort of how we’re thinking about racism and white supremacy as the foundation of all of the systems in the country.

This, from a professional journalist at the most powerful and important newspaper in the world. And Baquet hemmed and hawed trying to answer it! Nothing he said gives hope that the Times will approach race from any angle other than identity-politics ideology. Substitute the phrase “class conflict” for “race” in that paragraph above, and the ideological nature of the claim will be obvious.

Something big is happening, though. Read Bari Weiss’s op-ed about the $100 million deal that podcast host Joe Rogan — not a professional journalist — just made with Spotify.

But there is also a very practical reason Rogan can say whatever he thinks: He is an individual and not an organization. Eric Weinstein, another podcaster and a friend of Rogan, told me, “It’s the same reason that a contractor can wear a MAGA hat on a job and an employee inside Facebook headquarters cannot: There is no HR department at ‘The Joe Rogan Experience’.”

“When you have something that can’t get canceled, you can be free,” said Rogan.

The ability to be free of censorship is perhaps the thing Rogan prizes most — and he’s very concerned about censorship, especially inside the tech companies that control the most powerful forms of mass communication the world has ever seen.

I’m not a podcast listener, except when I’m driving (very little of that in the past three months), but the few times I’ve listened to Rogan makes it easy to get why he’s got such a massive audience. He brings real curiosity to his interviews with guests. You never really know what he’s going to ask, but you know that for all his many quirks (e.g., he’s a pothead), Rogan is a real person who has genuine curiosity in the people to whom he speaks. Weiss writes:

His whole ethos — curious; not particularly ideological; biased toward things that work; baffled by the state of both parties — is where so many Americans are right now. And that’s his power. He’s a mirror, when so many publications are broken glass, capable of reflecting only a shard.

Amen to that. Joe Rogan is one of the most popular and influential media figures in America, but he could never be hired at an American newspaper. Seriously, the little Robespierres in the cubicles would raise hell, and the lily-livered managers (like college presidents) would capitulate. Alas for journalism. Rogan is interesting because he’s interested in the world as he finds it, not as a screen onto which to project his ideological convictions.

There was a time when American journalism felt like that. It’s mostly why I became interested in doing it for a living. If a young person was genuinely interested in journalism for the right reasons, the ascent of Joe Rogan offers hope. We don’t need every journalist to be Joe Rogan. We need people who have been trained in the craft of investigative reporting, for example, and professional standards. But we need investigative reporters, and features writers, and national staffers, and everyone else in a standard newsroom, who can be more like Joe Rogan, approaching the world with curiosity, not an agenda, a chip on their shoulder, and fraudulent rationalizations for why the propagandistic approach they take to their work is actually morally and professionally correct. These are educated liberals talking to educated urban liberals about Things Educated Urban Liberals Believe. Who cares?

The Pulitzer Center is not the future of journalism. Thank God. The pothead podcaster’s success probably is. That’s good news. Look:

In my 7 years & 400,000 miles spent in lower income neighborhoods, talking to countless people, nobody ever mentioned the NYTimes, WP, or CNN, beyond a few unflattering remarks.

Everyone mentioned Radio, YouTube, & Instagram personalities

And Joe Roganhttps://t.co/RmwsjksfmK

— Chris Arnade ? (@Chris_arnade) May 25, 2020

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.