Amy Cooper, Race, And Mercy

To summarize my view of the Central Park confrontation between Amy Cooper and Christian Cooper:

1. Amy Cooper was wrong to have her dog off the leash in the park.

2. Christian Cooper was right to call her on it.

3. Amy Cooper ought to have apologized, then leashed her dog. She didn’t. She escalated.

4. Christian Cooper escalated too with a threat — “I’m going to do what I’m going to do, and you aren’t going to like it” — then calling her dog over to feed it something.

5. Amy Cooper then shot into the stratosphere — far beyond proportionality — by having a panic attack and making an explicitly racialized threat to Christian Cooper: to sic the police on him as a black man.

6. The police came and sorted it out without arresting anybody.

7. Christian Cooper (or his sister — I’m not sure) escalated this far beyond what was justified by posting video of the encounter on social media to humiliate and punish Amy Cooper.

8. The social media mob did what it always does: savaged Amy Cooper beyond what was proportional to her offense. She is now jobless, dogless, and if she is still in New York City, is probably afraid to go outside.

You know what this reminds me of? This incident that Ta-Nehisi Coates related in his megaseller Between The World And Me. He is addressing his son:

So. Ta-Nehisi Coates observes a white woman on an escalator behaving obnoxiously to his kid, but in a way that is (alas) ordinary in New York City. He immediately and instinctively racializes it. Ta-Nehisi Coates does not disclose it here, but he is a tall man. He lashed out at this woman from a place of racial rage (“hot with … all of my history”). A white man who saw a tall man yelling at a woman stood up for the woman — and Coates imputes racism to him (“attempt to rescue the damsel from the beast”). Bizarrely, Coates — who wrote this account years after it happened — can’t figure out why this stranger did not stand up for Coates’s little boy. As if a woman (wrongly!) giving a kid a push (we don’t know if it was a nudge or a harsh shove) and telling him to move on was the equivalent of a grown man screaming at a woman. For all we know from Coates’s account, the white man may not have known what started the argument. What he saw was that a large man was screaming at a woman. And when he confronted Coates, Coates shoved him.

Coates continues:

I came home shook. It was a mix of shame for having gone back to the law of the streets mixed with rage—“I could have you arrested!” Which is to say: “I could take your body.” I have told this story many times, not out of bravado, but out of a need for absolution. I have never been a violent person. Even when I was young and adopted the rules of the street, anyone who knew me knew it was a bad fit. I’ve never felt the pride that is supposed to come with righteous self-defense and justified violence.

Whenever it was me on top of someone, whatever my rage in the moment, afterward I always felt sick

at having been lowered to the crudest form of communication. Malcolm made sense to me not out of a love of violence but because nothing in my life prepared me to understand tear gas as deliverance, as those Black History Month martyrs of the Civil Rights Movement did. But more than any shame I feel about my own actual violence, my greatest regret was that in seeking to defend you I was, in fact, endangering you.“I could have you arrested,” he said. Which is to say, “One of your son’s earliest memories will be watching the men who sodomized Abner Louima and choked Anthony Baez cuff, club, tase, and break you.” I had forgotten the rules, an error as dangerous on the Upper West Side of Manhattan as on the Westside of Baltimore. One must be without error out here. Walk in single file. Work quietly. Pack an extra number 2 pencil. Make no mistakes.

Think about this. A white woman behaves with minor rudeness to Coates’s child. He escalates it massively, and racializes it. He physically assaults (though in a relatively minor way) a man who tries to defend the woman he is yelling at — and when the man quite rightly points out that Coates has violated the law, Coates interprets this as a threat to use the police to subdue and humiliate him, or worse. And years after it happened, Coates construes this incident as an example of the racial injustice of the civil order in a predominantly white neighborhood. Presumably if the Upper West Side — one of the most liberal neighborhoods in the US — were racially enlightened according to Coates’s standard, enraged black men could yell their heads off at white women in public places, and everyone would stand back and let it happen, to show their racial bona fides.

What’s telling about this incident is that not that Ta-Nehisi Coates behaved that way in public when a stranger treated his kid that way. Most fathers would react with anger; I know I would. What’s telling is that he immediately racialized it, and even years later, rationalizes his own ridiculous behavior. He was not wrong, as he sees it, to blow up at a woman over a minor incident. He was not wrong to bring race into it without justification. He was not wrong to shove a man who came to the defense of the woman at whom he, Coates, was screaming.

Coates only did wrong, in his telling, because he put his son in the position of seeing his father abused by the police. As if the NYPD responds to every altercation involving a black man by using abusive, even fatal, force. A story that ought to have been remembered by him with regret, as a time when he let his emotions get the better of him, Coates renders as a testimony to his status as a victim of white society.

Ask yourself: if a white man had blown up in a public place at that white woman over her minor offense, and had shoved a stranger who came to defend her, who would be seen as the villain of the story? Is there any sense in which a white man could behave that way towards others and be legitimately seen as the victim? Had the Coates role been played by a white man, the woman would have probably told the story as an example of the threat women have to deal with from “toxic masculinity.”

Coates tells this story of himself behaving badly (but still being the victim!) in a book that became a massive bestseller, and won the National Book Award. Coates is a multimillionaire who is now seen as a sage on race in America. After a mild confrontation in a public space, Amy Cooper panicked — why, we don’t know — and wrongly racialized her encounter with a tall black man in Central Park, calling the NYPD on him. Nobody was hurt, thank God; the police let them both go. She was wrong to have done what she did, and she has admitted it, and apologized. But her life is a ruin now because of what happened.

This is not a defense of Amy Cooper, who behaved quite badly. It is interesting, though, to think about how these two similar New York incidents had such radically different effects. Both Cooper and Coates wrongly brought race into an ordinary urban conflict in a city full of edgy people, thus throwing gas on a fire. Coates doesn’t regret what he did, except in a backhanded way, and uses the incident as part of crafting his lucrative public persona on a worldview of unappeasable racial grievance.

I say “unappeasable” because TNC makes it very clear in his writing that he doesn’t expect anything to ever get better in race relations. Forgive me, regular readers, for repeating a story you’ve heard before, but because a lot of people will only come to this post from the outside, not knowing these stories, I have to repeat them here. In a piece I wrote here a couple of years ago, I did a thought experiment to try to understand why he believes the things that he does, even against the evidence. Excerpts:

In this post, I want to think out loud about how and why it is that Ta-Nehisi Coates, a writer and thinker of such sensitivity and promise, gave himself over to racialized despair. Some might say that’s because it makes him a lot of money, and it has brought him immense prestige in liberal circles. But that is unfair. Coates thought and wrote like this before he was rich and famous. I think his wealth and his fame, coming as they have because his racialized despair is very much of our cultural moment, will make it much harder for him to break out of it. Still, it was his before there was money and fame in it, and however blind his race theory makes him to the complexities of American life and American politics, it’s not fair to call him cynical.

I recalled in the post (quoting TNC) how TNC went from being a standard progressive on race, expecting that things will improve over time, to losing all hope that that would ever happen. More:

Reading this tonight, I tried a little experiment in empathy. Is there anything that happened to me that can give me even a little feeling for what this experience was like for TNC? The closest thing I could think of was the four or five years I spent writing about the abuse scandal in the Catholic Church, before I lost my Catholic faith.

The details of that experience are very familiar to longtime readers of mine, so I won’t bore you with them again. But I need to point out a couple of things.

First, TNC described his prelapsarian self as holding this view:

It seemed logical, to me, that this progress would end–some day–with the complete vanquishing of white supremacy.

He set himself up to be disillusioned because he expected of liberalism something it couldn’t deliver. (“To expect too much is to have a sentimental view of life and this is a softness that ends in bitterness.” — Flannery O’Connor). He really seems to have thought that we were moving inexorably to the elimination of that particular evil in this world. And we are! It is absurd to claim that an American black man in 2018 is no better off than an American black man in 1948 (where in much of this country he was subject to lynching), or an American black man in 1848, under slavery. It is impossible to take the claim of no moral progress against white supremacy seriously. In 2008, a black man won the US presidency with 43 percent of the white vote. The idea that white supremacy’s grip on America is as strong as ever is as absurd as claiming that racism is over, because we elected a black president.

My point is, TNC sounds like was once a sentimental liberal who hadn’t yet grappled with the depth and complexity of the evil wrought by white supremacy.

I get that. I was a sentimental conservative Catholic who had no idea what kind of evil I was about to walk into when I started writing about the scandal (in 2001, before it broke big nationwide). Father Tom Doyle, the brave Catholic priest who made his reputation by testifying in court for victims, warned me at the outset that I was headed to a place darker than I could imagine. He wasn’t trying to discourage me at all, but rather caution me to prepare for the worst. I thought I had. I was very, very wrong.

But then, I don’t know what I could have done to make me ready to stare into that particular Palantir and not fry my mind. In time I came to resent, and at times despise, my fellow conservative Catholics who tried to dismiss or denature the scandal with phrases like, “Yes, the American bishops haven’t exactly covered themselves in glory, but …”. The Catholic writer Lee Podles’s book Sacrilege is as close as I’ve ever seen anybody come to recreating and concentrating that extremely painful disillusionment. I couldn’t get past the first few chapters, because it was like reading the Necronomicon. Don’t get me wrong: Podles is a faithful orthodox Catholic, but he told the unvarnished truth, uncovered from his investigation, and from poring over case files. These things really happened. It’s straight hellfire.

The result for me was to be left unable to remain a Catholic. Imagine sticking your hands into an open flame, holding them there for ten seconds, then trying to pick up a Bible with it. The broader effect was to leave me incapable of fully trusting religious authority figures. I don’t even try to do so, not one bit more than I absolutely have to for the sake of practicing my faith. Having seen the extremely perverse lies they can tell to protect their own perceived interests, including the lies they tell themselves, I can’t be party to it. This is not a confession of moral and spiritual strength, but rather one of moral and spiritual weakness.

So: I can see a parallel between my experience and TNC’s. We both held naive faiths in particular institutions and myths — mine in Roman Catholicism and the institutional Catholic Church, and his in Progress, and the institutions of liberal democracy. We both got waylaid by history and the evil that men do, and emerged chastened, even broken.

He has spent the rest of his career writing extremely downbeat, deterministic, fatalistic essays about the unique iniquity of white supremacy, and how it can never be defeated. He has given himself over, in my reading, to a view of humanity that is entirely circumscribed by race. And not just by race, but by a strict reading of racial dynamics in which whites are most themselves when they are evil, and in which blacks, even when they behave in evil ways, do so because one way or the other, they have been made that way by whites.

This is a popular thing to believe nowadays. You can get a MacArthur genius grant for peddling that kind of despair, and win the National Book Award. Still, it’s authentic with Coates.

As a thought experiment, I’m wondering what would have happened to me had I followed his intellectual path from my own disillusioning experience. It’s hard to see a clear parallel, though I suppose it might have been to write books and essays on the evil of organized religion, and how all religion is a scam through which the powerful exploit the weak, or something.

Instead, though I left the Catholic Church, and though I have kept a clear distance from institutional Orthodoxy (I learned from a lapse early in my Orthodox years that I should stay away from church politics), I have not despaired of Christianity. Indeed I have been chastened — severely chastened — by what I learned, but I have also been chastened by my intellectual pride, and my naive idealism. The scandal pretty much beat the religious triumphalism out of me, and it left me with a deep awareness of my weakness for believing certain narratives. I’ve thought a lot over the years about Catholics who saw what I did, who didn’t minimize or dismiss its seriousness, but who kept the faith. Though I’m definitely not returning to the Catholic Church, I think what they have is an important disposition for all Christians to cultivate. I’ve tried to do it within myself.

What helped me was understanding that the same Church, and same tradition, that cultivated within it the evils of the child sex abuse scandal (as well as a long litany of crimes over the centuries) also produced St. Benedict and Dante Alighieri, both of whom came into my broken life bearing grace and good news that healed and gave me hope. The black experience in America has been one of suffering immense evil, but out of that experience came art of astounding beauty and feeling, and prophetic vision. Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Martin Luther King Jr. — could any of them have emerged from the kind of despair that has engulfed TNC?

I don’t think anybody can claim that those men minimized or dismissed white supremacy and its wickedness. Somehow, they saw through it, to a deeper reality. They had hope — not optimism, but hope.

In the summer of 2002, I was struggling with rage over 9/11, and on top of that, the sex abuse crisis. My wife begged me to get professional help. On the first day I met with a Christian therapist, he told me that in our work, he was going to help me to understand that under the right set of circumstances, I too could have been piloting one of the planes that the terrorists flew into the World Trade Center. I was furious at him for saying that! No way could I ever be that kind of man. The therapist and I ended our professional relationship after a couple of months over other things, but I still resented him for making such a preposterous claim.

It took me years, but I learned in time that the therapist was right. As I have said here many times, my rage at the 9/11 terrorists led me to rationalize supporting the Iraq War. I didn’t see the Iraqis as people; I saw them as a representative of the people (Arab Muslims) who had caused such murder and destruction to my city and my country. I was part of a culture, professionally and otherwise, that affirmed that rage, and affirmed the response (war) that I was talking myself into supporting, calling it justice.

The thing that is so difficult to convey to others is how little self-awareness I had at the time — and believe me, many, many of us were like that. I was genuinely appalled by the therapist’s suggestion that I could find myself one day in the pilot’s seat of a hijacked airliner. What he was trying to do was to get me to a place where I could forgive, in some real sense, the hijackers, and in so doing free myself from the weight of my rage.

But I was part of a mob, more or less — a mob that was of righteous mind, and that believed by harboring doubts about the proposed war, we were breaking faith with the victims of Arab Muslim terrorism. Whatever else I (and many other war supporters) were, we were not cynics. But we were wrong. People like me were willing to fly the US military into the side of a country, Iraq, that had not attacked us, because some Arab Muslims had attacked us, and therefore any Arab Muslim, in my view, had to pay. That wasn’t what I told myself consciously — but it’s what I believed, deep down. That self-knowledge would come later.

Catholics have reason to claim that I made the same mistake, letting rage overcome my Catholic faith. They could be right. I addressed this above. I am grateful to be an Orthodox Christian, and grateful too to have been freed from my anger at the Catholic hierarchy. But as I said above, recognizing in the aftermath of all that how my passions in the face of real and horrible injustice overcame my ability to think and act clearly forced me to try to approach life differently. A person who is in the grips of passion — even righteous passion — can do terrible things. A mob in the grips of passion is one of the most destructive forces on earth.

I am an emotional person, no doubt about it. The point of growing in maturity, and growing as a mature Christian, is to learn how to master your own passions, lest they master you. I will be struggling in this way until they day I die. All of us should be. One of the great lessons I learned from studying the testimonies of Christian political prisoners under the communist regimes is how even though they were treated unjustly, and even tortured, they never, ever gave in to self-pity, or hatred of their persecutors. How they did this is some kind of miracle — but it is vital wisdom for our time.

In my next book Live Not By Lies, I tell their stories, within the framework of the “soft totalitarianism” coming upon us. What has happened to Amy Cooper is a recent example of soft totalitarianism, and it has nothing to do with whether or not she is guilty or innocent of a moral offense. Under communism, people had to be scared of their neighbors, and of anybody outside of their family or very close circle of friends. You had to watch every word or gesture you made around people you couldn’t absolutely trust, because you never knew if they might be an informant. It completely poisoned social life.

And here we are in 2020, recreating a softer version of this. The state was not involved in the Cooper case, or in the Covington Catholic case, or in any of these cases in which the online mob turns out supposed malefactors based on a viral video (which may or may not tell the truth of what happened in a conflict). But the mob’s actions caused catastrophic real-world effects for real people. What kind of society are we building, when people have to be afraid that what they say in private could be recorded and broadcast to the public, for the sake of causing their own destruction? Or their worst public moments could be captured on video and shared with the entire world — and there will be no redemption for them? I’ll tell you what we’re building: a society that has turned inward out of self-protection, in which solidarity is next to impossible to build, because everyone has to be afraid of everybody else.

And the state doesn’t have to be involved at all.

If we at least tried to live by a Christian ethic, one that elevated mercy and forgiveness, we would be in better shape. Not perfect shape, but better, because we would have an ethic that, if practiced, would call us toward humility and mercy. But we are post-Christian now. Mercy and pity are signs of weakness. Rage is a measure of one’s authenticity. The line between good and evil does not pass down the middle of each person’s heart, as Solzhenitsyn learned in the gulag, but rather, as we see it, between the races, between the secular and the religious, between economic classes, and so forth. We absolve ourselves in advance, and nurture grievance, because we think it gives our lives meaning.

Amy Cooper looked at Christian Cooper and saw — well, what did she see? Did she see him as a real threat? Possibly. Did she see his blackness as a weapon that she could use against him? Absolutely. And in this, she was grievously wrong. He was correct to record their confrontation. To her, Christian Cooper was not a person, but a symbol of whatever she felt was threatening to her — even if it was merely threatening her sense of privilege (that is, the “right” she felt she had to flout the rules of the park). She hoped to be able to cause him harm because of his race. Thank God she failed.

But after it was over, and it had been resolved by the police, Christian Cooper knew that he had in his phone something that could ruin her life: that video. Either he, or his sister (I’m not clear which), made it public. By now, nobody is innocent of what social media mobs can do. Amy Cooper had become in their eyes nothing but a symbol of white privilege and racial animosity. Not a human being, but a symbol. Today, we live in a world in which people of the left and the right alike can be rewarded handsomely for making hate symbols of flesh-and-blood human beings, and causing others to give in to primitive hatred. The President of the United States does it, especially on social media — but don’t for a second believe that he is anything other than a product of this culture. There are leftists who quite rightly denounce him, but who are blind to the capacity for blind, destructive hatred in themselves.

I know this because at one time in my life — from 9/11/2001 until about a year after the war started — I was inside my own version of it.

This petty, nasty woman, Amy Cooper, is professionally and personally destroyed. Go on Google News and type her name in — in the media and online, Amy Cooper is the new Bull Connor. It is extraordinary. She will never recover from this. Could anybody? And now the state — that is, the city government — is getting involved: the NYC Human Rights Commission is planning to bounce the rubble of her life by investigating her, and is reminding her that they could impose huge fines on her. If Amy Cooper has any sense, she will flee the city and not look back.

What she tried to do to Christian Cooper was unjust. But is this justice? Is this the kind of world any of us — white, black, Latino, Asian, secular, religious — want to live in?

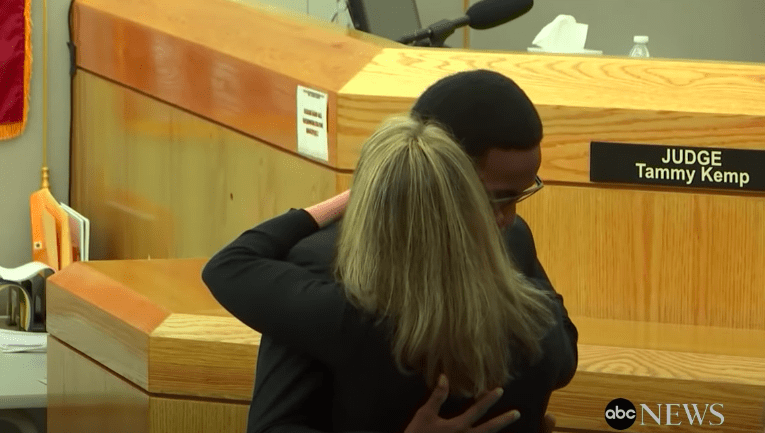

I don’t. I want to live in a world in which Brandt Jean are rewarded. He is a black Christian in Dallas whose brother Botham was killed by off-duty white female cop Amber Guyger. She was convicted of wrongful death, and at her sentencing, that young black Christian man, Brandt Jean, gave her forgiveness. He urged her to seek Christ, and to give her life to Him. With the (black female) judge’s permission, he also gave her a hug:

And then, after that was over, Judge Tammy Kemp went into her chambers, brought out her personal Bible, and gave it to Amber Guyger. Watch it here. She told Guyger to start with John 3:16. Guyger hugged her, and said something in her ear. Reporters heard Judge Kemp say, “Ma’am, it’s not because I’m good. It’s because I believe in Christ.”

This black man, Brandt Jean, and this black woman, Tammy Kemp, are heroes of mercy. Because of what they did that day in the courtroom, it is possible, and probably even likely, that the rest of Amber Guyger’s ruined life — a life she ruined by shooting and killing Botham Jean — will be redeemed, and that she will know eternal life. If you are not a Christian, though, I still believe that all of us would prefer to live in a society that esteems the mercy shown by Mr. Jean and Judge Kemp — mercy, even amid the formal administration of justice (Guyger got ten years).

You don’t want to be Amy Cooper. But you also don’t want to be leading the mob that’s tearing her from limb to limb. You want to be Brandt Jean and Tammy Kemp. At least I do. All have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God. There is none righteous, not one. Let he who is without sin cast the first stone.

This matters, y’all. Brandt Jean will never get a MacArthur grant, or be the object of worship by the cultural establishment. But he is telling us, and showing us, how to live in truth — the kind of truth that will save us from our worst passions, if we want to be saved.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.