The Agony Of Fortnite Addiction

A number of you have sent me the Wall Street Journal article about the game Fortnite, and how it has set off an “unwinnable war” between boys and their parents. The article is behind the Journal‘s paywall, but I managed to get a copy of it from a friend who subscribes. I’ll quote from it below.

The writer, Betsy Morris, spends time with some adolescent San Francisco boys who are immersed in Fortnite, a multiplayer (bloodless) shooter game that is the most popular electronic game on the planet. The obsessive nature of the game has long been observed among parents. Nick Paumgarten writes:

Parents speak of it as an addiction and swap tales of plunging grades and brazen screen-time abuse: under the desk at school, at a memorial service, in the bathroom at 4 a.m. They beg one another for solutions. A friend sent me a video he’d taken one afternoon while trying to stop his son from playing; there was a time when repeatedly calling one’s father a f–king a-shole would have led to big trouble in Tomato Town. In our household, the big threat is gamer rehab in South Korea.

The WSJ set out to see what that addiction looked like in the lives of Toby, Matthew, Max, Jaren, and Reed, a group of Fortnite-loving friends who live in the same San Francisco neighborhood. Excerpts:

These seventh-grade pals used to spend their after-school hours together, either at somebody’s house or nearby Rochambeau Park. Now, they spend most of their free time apart, sequestered in their respective homes playing Fortnite and chatting through headsets instead of in person.

Not long ago, boys this age would be agitating for a trip to the movies or the skate park, someplace to hang out together. Not now.

“We see each other eight hours a day at school,” Toby said. Going to the park, Matthew said, is boring compared with Fortnite.

In less than 18 months, “Fortnite: Battle Royale,” a last-man-standing shooting contest, has grabbed onto American boyhood, joining, or pushing aside, soccer, baseball, even a share of mischief. Girls find it far less appealing.

The WSJ says that Fortnite is changing the way boys communicate. You can log onto the game at any time, and boys communicate with each other through the open line via their headsets. The game “can also tear at family relationships in a way that few, if any, videogames have done before.”

Some critics say this is just a new fad, and like with many other fads, Parents Just Don’t Understand. But this greatly underestimates the neuroscience behind Fortnite. The game learns from its players how to keep them engaged. More:

As games get smarter, parents feel outmatched. “It’s not a fair fight,” said Dr. Richard Freed, child and adolescent psychologist and author of “Wired Child: Reclaiming Childhood in a Digital Age.”

Fortnite feels to some like an uninvited visitor, one that refuses to leave.

Oh boy, I’ll say. Read this:

Parents have long used favorite childhood activities to help teach moderation and self- restraint: Be home by dark; no TV until your homework is done. The struggle at Toby’s house illustrates the deficiency of those methods.

Toby is “typically a nice kid,” his mother said. He is sweet, articulate, creative, precocious and headstrong—the kind of child who can be a handful but whose passion and curiosity could well drive him to greatness.

Turn off Fortnite, and he can scream, yell and call his parents names. Toby gets so angry that his parents impose “cooling off” periods of as long as two weeks. His mother said he becomes less aggressive during those times. The calming effect wears off after Fortnite returns.

Toby’s mother has tried to reason with him. She has also threatened boarding school. “We’re not emotionally equipped to live like this,” she tells him. “This is too intense for the other people living here.”

Mr. Ghassemieh, Toby’s father, is a former gamer who works in the tech industry. He believes a game like Fortnite can help children learn analytical skills. Yet, he is bothered by how all the stimulation affects Toby.

“Join the family for dinner? ‘What? I was just in a gunfight and you want me to sit down and have a nice meal?’” Mr. Ghassemieh said.

Toby has a different point of view: Everybody else’s families can handle Fortnite, he said. Why can’t his?

It’s the same story for all these parents. Author Morris goes to a meeting about Fortnite for parents, where Common Sense Media, the nonprofit parents’ resource on child media use, was making a presentation. Astonishingly, the presenter thought his job was to convince parents to chill out about Fortnite. They weren’t having it.

The message wasn’t what many parents had come to hear. One woman drew applause when she raised her hand to interject: “This has been almost a celebration of Fortnite. I’m waiting for the part that would be useful to us.”

As people filed out early, one parent asked, “What advice do you have for us families who want less Fortnite in their life?”

What’s going on with the brain during Fortnite is akin to what keeps gamblers locked in to slot machines, the Journal says.

“When you follow a reward system that’s not fixed, it messes up our brains eventually,” said Ofir Turel an associate professor at California State University, Fullerton, who researches the effects of social media and gaming.

With games like Fortnite, Dr. Turel said, “We’re all pigeons in a big human experiment.”

Got that? Every kid playing Fortnite is being experimented on. Gamblers at least are adults, with fully-formed brains. What does this stuff do to the brains of kids who are still growing? Nobody knows. Yet. More:

Dr. Freed, the psychologist, said the study of addictive technologies has identified some 200 persuasive design tricks. Fortnite has so many of those elements combined, he said, that it is the talk among his peers. “Something is really different about it,” he said.

He said its intentional design helps explain why parents have such trouble fighting the game’s pull on their children. As parents try to teach moderation and limits, Fortnite seeks a player’s full engagement for as long as possible.

Here’s how dominant Fortnite is among adolescent and teenage boys. One of the San Francisco fathers took Fortnite away from their son Max when his grades dropped. The boy’s mother noticed that Max was losing contact with his friends, all of whom were so deeply wired into the game. More:

At Matthew’s house, Fortnite is making life uncomfortable. His father, Jay Seiden, a senior director at real-estate brokerage Cushman & Wakefield, doesn’t understand why Matthew isn’t outside playing or exploring the nearby parklands and beaches, said Ms. Woods, Matthew’s mother. As a boy, Mr. Seiden would ride his bike or play in creeks, catching frogs and snakes.

Often, Mr. Seiden forces Matthew off Fortnite after 90 minutes and sends him outside. Then, his mom said, she sees him riding up and down California Street on his scooter looking for friends.

She imagines they are all inside playing Fortnite. Matthew’s mother grew up in Chevy Chase, Md., and was an avid gamer, staying awake for hours after her parents were asleep playing Ms. Pac-Man, Donkey Kong and Frogger. She still rode her bike, got homework done and earned a law degree.

That is why she is more lenient than Matthew’s father. Friday nights are Matthew’s favorite time of the week. He gets macaroni and cheese for dinner and Fortnite until bed. Ms. Woods sets time limits, she said, but “I probably let him play too much. I’d rather not fight about it.”

Read the whole thing, if you have a subscription. It’s fascinating.

Much of this resonates with me. One reader, knowing that I have a 14-year-old boy, asked me how my wife and I dealt with the Fortnite challenge. The answer is simple and blunt: we don’t let our son have Fortnite, period. We can see the way it affects other kids, and believe it is our obligation to protect him from that.

He’s suffering from it, in a particular way. He says that all the boys in his class are into Fortnite, and that that’s all they talk about — Fortnite, and their favorite YouTube stars (some, like PewDiePie, who has 78 million followers, being foul-mouthed people you wouldn’t let in the front door of your actual house, but to whom your son has open access). Not music, not sports, none of the usual teenage boy discussion fodder. Only Fortnite and YouTube. Our son has tried to be big about it, but not playing Fortnite (or being allowed to watch YouTube) has socially marginalized him among his peers. His mother and I try hard to be sensitive about that. But we can’t budge on this game.

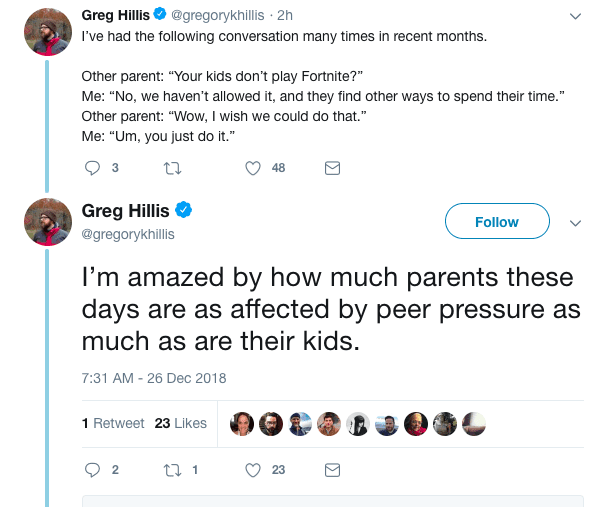

Here’s what I genuinely do not understand: why so many parents are afraid to be parents. Why did those people have to go to a public meeting to find out what to do about Fortnite addiction in their boys? Pull the plug on it, and don’t look back! Is it really that hard to know the answer? The moms and dads in this story despise the effects this game has on their boys. Toby, for example, is a sweet kid normally, but when he’s on Fortnite, it’s like the game possesses him. But his mom would “rather not fight about it,” so he gets his way.

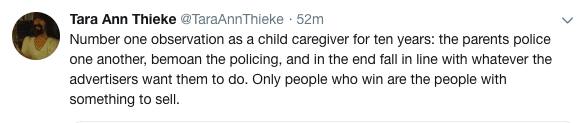

I find that to be true of a lot of parents, even those who consider themselves to be conservative and religious. They give in to things that they know they shouldn’t accept because they don’t want to fight with their kids about it. And, I have seen evidence that the compulsion to conform to socially permissive norms overwhelms many parents. I guarantee you that if one couple in that social group cut their kid off permanently from Fortnite, they would not only catch hell from their detoxing child, but would be pressured to relent by other parents, who secretly feel guilty that they aren’t doing what needs to be done, and deal with their guilt by scapegoating the mom and dad who took the hard but necessary stand.

Look, these are your children. We live in a culture that is hostile to them and their moral, mental, and emotional health. You cannot depend on the norms and customs of this culture to support you in raising good kids. You have to push back, and push back hard, for their sake. They need you to be mom and dad, not their buddies or allies. Deep down, you know this. Do the right thing. It’s a hard thing, but what is the alternative?

Leaving aside all the childhood things that these kids are not getting because they’re on Fortnite all the time, and leaving aside what may be happening to their neurological development, why is it not crystal-clear to parents that a child whose body becomes accustomed to that dopamine rush is not likely to turn into an adult who can manage his passions?

I had a conversation this fall with a foreign scholar who is on a kind of exchange program at a tippy-top elite American university. He told me how strange it is to observe how anxious and unstable American undergraduates and even grad students are. He said they struck him as brilliant but neurotic, because they have been raised by a meritocratic and technocratic culture that gives them no grounding in anything outside of themselves and their desires, which includes a compulsion to climb to the top of the meritocratic heap. And for what? They can’t really tell you.

Phenomena like Fortnite are part of what malforms us. It’s not the content of the game; it’s the format of the game. The medium really is the message here. The psychiatrists and scientists interviewed by the Wall Street Journal tell you that scientists working for the game designer are constantly improving (“improving”) the game to make it even harder to quit. In The Benedict Option, I have a chapter on technology that addresses things like this. Excerpts:

When we abstain from practices that disorder our loves, and in that time of fasting redouble our contemplation of God and the good things of Creation, we recenter our minds on the inner stability we need to create a coherent, meaningful self. The Internet is a scattering phenomenon, one that encourages surrender to passionate impulses. If we fail to push back against the Internet as hard as it pushes against us, we cannot help but lose our footing. And if we lose our footing, we ultimately lose the straight path through life. Christians have known this from generation to generation since the early church.

But with us, this wisdom has been forgotten. Laments Nicholas Carr, “We are welcoming the frenziedness into our souls.”

More:

Chris Anderson, a former top tech journalist and now a Silicon Valley CEO, told the New York Times in 2014 that his home is like a tech monastery for his five children. “My kids accuse me and my wife of being fascists and overly concerned about tech, and they say that none of their friends have the same rules,” Anderson said. “That’s because we have seen the dangers of technology firsthand. I’ve seen it in myself, I don’t want to see that happen to my kids.”

If that’s how Silicon Valley tech geniuses parent, how do we justify being more liberal? Yes, you will be thought of as a weirdo and a control freak. So what? These are your children.

“The fact that we put these devices in our children’s hands at a very young age with little guidance, and they experience life in terms of likes and dislikes, the fact that they basically have technology now as a prosthetic attachment—all of that seems to me to be incredibly short-sighted and dangerous,” says philosopher Michael Hanby.

“It’s affecting their ability to think and to have basic human relationships,” he said. “This is a vast social experiment without precedent. We have handed our kids over to this without knowing what we are doing.”

The saddest image from the Journal story is the boy whose parents took Fortnite away from him, pedaling his bike through his neighborhood, and finding no one to play with because all the other boys are isolated inside their homes, playing Fortnite in virtual reality. I know the loneliness of a boy like that, because I see it in my own son when he talks about what school is like. Still, we can’t surrender to this thing. What we don’t master masters us.

In The Benedict Option, I quote William James, the founder of psychology, saying that who we are depends on what we pay attention to. I got that insight from Columbia University’s Tim Wu, whose book The Attention Merchants is a history of advertising as an epic contest to win the attention of consumers. It might sound like a relatively dry topic, but trust me, this book is riveting. When you get to the last part, when Wu describes how companies are investing tens of billions on scientists to figure out how to reach you and mold your desires without you even knowing what’s happening, you’ll understand why, in the case of Fortnite, “come on, it’s just a game” is a shockingly irresponsible response to critics.

UPDATE: A reader writes:

I read your article on Fortnite with more than a little skepticism (Not least due to the title “The Agony Of Fortnite Addiction”. One imagines similar articles in previous eras, “The Agony of Dime Novel Addiction”, “The Agony of Comic Book Addiction”, “The Agony of Atari Addiction”, etc.) But by the end, I would concede two points, which I actually think you did not emphasize enough.

1) Because of the amounts of money involved, the psychological engineering behind these services is getting stronger. I don’t think you can reasonably deny that video games have simply gotten more engrossing over time, due partially to higher vividness, but also due to the continuing development of the practice of video game design. The exact degree of effect is unclear, but there’s some good economics work to support this idea (https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2017/03/30/the-link-between-video-games-and-unemployment )

2) But actually when I think about my time playing video games as a kid (and I was an avid gamer), something else actually stands out more. It would be hard to be more engrossed than I was by games like Star Wars Knights of the Old Republic (a role-playing game) or the Medal of Honor series (a first-person shooter). You’re either engrossed or you aren’t. But they absolutely did not play a major role in my social life. To the extent that a game had come out that everyone wanted to play together, you had to do so, in person, at someone’s house. That had two effects: 1) you still had in person bonding, and often physical activity (a perfect afternoon was basketball, followed by pizza, followed by Goldeneye on N64) and 2) it provided natural limitations on the addictive combination of video games + friends.

I was in college when online multiplayer video games began to become a big deal outside of the gaming community (there have been online video games since at least the 1990s, but for essentially technical reasons, they were pretty limited until so-called 7th generation consoles: Xbox360 and Playstation 3). Since then, it has exploded. Anecdotally, the people I know who got into online gaming have had way more problems with addictive-like behavior. It can quite easily become the most important social interface, with both your IRL (in real life) friends on the platform and new friends that you make online. I can only imagine this being amplified in high school.

So I think the real problem with Fortnite is not that it’s particularly well designed from a psychological point of view. Actually, I can prove it. There are some games that are designed to hack your dopamine receptors for money: think Candy Crush, Farmville, or other games designed to get you to pay money to access the “high” of success by taking a kind of shortcut that you’d otherwise have to work harder at in terms of time/skill in the game. But how does Epic make money in Fortnite? It’s a free-to-play game, and there are ZERO in-game-success-hack type things you can buy. (you can’t buy anything that will improve your playing experience, unlike many other games like Fortnite). ALL of Epic’s hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue comes from COSMETIC upgrades — different skins, dances, and items that only appear to other players in the game. In other words, that ONLY have social value.

What is unique about Fortnite, and what distinguishes it from any video game fad before, is that it has a lot more in common with the other kinds of high school fads which come and go with every generation. It has hacked the social graph — become a place for connection, status contestation, and identity amongst high schoolers (and by the way, the article you posted said Fortnite is far more popular with boys than girls. Balderdash. Fortnite is the most popular video game with girls, ever, by a wide margin) (this article makes some of these points: https://medium.com/s/greatescape/fortnite-is-so-much-more-than-a-game-3ca829f389f4). In some ways, it offers a seductive alternative to the classical sources of male friendships. Boys want to hang out, together, and have adventures. But there are all kinds of practical constraints on the ability to hang out and what you can do or get away with on your “adventures”. With Fortnite, you can connect with your friends and minutes later by engaging in epic winner-take-all fantasmagorical battles. (That’s another Aaron Renn-esque point. When you neuter agonism or competition in society, maybe the few places it reappears become more alluring).

In that way, it reminds me of an excellent essay by Daniel Mendelsohn in the NYRB about James Cameron’s Avatar (https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2010/03/25/the-wizard/). The real message of Avatar (and of Cameron’s oeuvre, he argues), is that technology will enable us to build more and more powerful escapes, and then to live in the escape, rejecting a return to reality-adulthood (he sees Avatar as a reversal of The Wizard of Oz). This is only the beginning.

UPDATE.2:

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.