He Revealeth The Deep And Secret Things

Terrence Malick is a difficult filmmaker. I mean, he is a maker of difficult films. They are thematically deep, narratively dense and disjointed, and pictorially gorgeous. When he’s at the top of his game, as in The Tree Of Life, it’s like watching religious icons come to life. I would say his To The Wonder is the same kind of movie. But when he’s missing the mark, as in his recent Knight Of Cups, it feels like an obscurantist mess.

Malick is a Catholic an Episcopalian, and a profoundly philosophical and theological filmmaker. Read this analysis of To The Wonder to get a sense of what he’s up to. The reason Mont-Saint-Michel is on the cover of The Benedict Option is because of how Malick uses the abbey in that movie: as a symbol of God’s eternal presence in time, calling us back to Himself — and, secondarily, about how we have to establish temporal, material boundaries for the experience of Love (love of God, love of others), or we will lose it. Back in 2013, when To The Wonder came out, Damon Linker wrote a good piece about it. Linker laments the inability of contemporary film critics to see beyond the surface of Malick’s movies. In this excerpt, he’s talking about a Catholic priest, played by Javier Bardem, who serves the poor and the broken, but who feels very far from the experience of God:

That so many reviewers have either ignored Father Quintana’s role in the film, or seen his struggles as an uninteresting subplot unrelated to the movie’s exploration of romantic and sexual love, is perhaps the most stunning critical oversight of all. Just as Neil holds himself back, refusing to give in to all that love demands, Father Quintana often fails to detect the presence of God all around him and sometimes withholds himself from the most troubled and troubling people to whom he’s called to minister (including prisoners and drug addicts).

Yet unlike Neil, who ends up alone, Father Quintana achieves a spiritual epiphany during a sequence toward the end of the movie that is unlike any I have ever encountered in film, and one I have not seen referenced in a single mainstream review. As the priest comforts a succession of suffering people — the old, the anguished, the crippled, the sick, and the dying — he recites a devotion of St. Patrick: “Christ be with me. Christ before me. Christ behind me. Christ in me. Christ beneath me. Christ above me. Christ on my right. Christ on my left. Christ in the heart.” The sequence reaches its climax with the recitation of a prayer by Cardinal Newman (one that was also prayed daily by Mother Teresa’s Sisters of the Missionaries of Charity): “Flood our souls with your spirit and life so completely that our lives may only be a reflection of yours. Shine through us. Show us how to seek you. We were made to see you.”

Humanity was made for God. And he is present all around us — in the transfiguring, wondrous joy of romantic love, in self-giving sacrifice, in our suffering and the suffering of others, in the charity we offer to those in pain, in the resplendent beauty of the natural world — if only we open our eyes to see him. That, it seems, is Terrence Malick’s scandalous message.

Here is that sequence. Tell me, where would you ever see something like this in a modern movie?:

It has been six years since I saw To The Wonder, and not a week goes by when I don’t think about it. I’m serious. So often I feel like Father Quintana: knowing God is there, but for whatever reason, feeling exiled from His presence. Other times I feel like the Olga Kurylenko character: feeling God everywhere, but lacking the discipline to bound the experience of Him with practices that will remind me of His reality when I’m not feeling it.

Truly, it’s a great, great movie. But it’s not an easy movie. This is art. It demands a lot from you. I can understand why the critics didn’t get it. Malick’s head is deep into a Christian philosophical and theological framework. Most ordinary Christians too have lost the ability to read this filmic icon.

For example, the Ben Affleck and Olga Kurylenko characters fall deeply in love when they visit Mont Saint Michel, and are shown in the inner garden of the monastic cloister. Medieval monks regarded those enclosed gardens as a representation of the Garden of Eden (and, in turn, the Virgin Mary’s womb): the place where man had an unmediated, direct experience of God. Later, Affleck proposes marriage to Kurylenko in the Luxembourg Gardens in the heart of Paris — also an enclosed garden. Malick uses this symbolism to say something about the nature of the love that his protagonists experience at that point in their lives. Then, Affleck moves his new wife and daughter (from Kurylenko’s previous marriage) to Oklahoma, where everything is flat and wide-open. In this new physical space, their love will be tested.

See what I mean? Because Malick is a real artist, he doesn’t bludgeon you with the symbolism. But a film critic who didn’t understand anything about Christianity, and a Christian whose idea of Christianity is shallow, emotional, and moralistic, will be puzzled by what they see.

All that came to mind last night when I read the review of A Hidden Life, the new Malick movie, in The New York Times. The film is a mediation on the life of Franz Jägerstätter, a simple Austrian Catholic who was imprisoned, tortured, and murdered by the Nazis for refusing to serve Hitler (Benedict XVI beatified him). The Times’s lead critic A.O. Scott admires the movie aesthetically, but he confesses that the behavior of Jägerstätter is a mystery to him:

The mystery — and the possible lesson for the present — dwells in the question of Franz’s motive. Why, of all the people in St. Radegund, was he alone willing to defy fascism, to see through its appeal to the core of its immorality? His fellow burghers, including the mayor, are not depicted as monstrous. On the contrary, they are normal representatives of their time and place. Franz, whose father was killed in World War I, who works the land with a steady hand, a loyal wife and three fair-haired children, seems like both an ideal target of Nazi propaganda and an embodiment of the Aryan ideal. How did he see through the ideology so completely?

The answer has to do with his goodness, a quality the movie sometimes reduces to — or expresses in terms of — his good looks. Diehl and Pachner are both charismatic, but their performances amount mainly to a series of radiant poses and anguished faces. Franz is not an activist; he isn’t connected to any organized resistance to Hitler, and he expresses his opposition in the most general moral terms. Nazism itself is depicted a bit abstractly, a matter of symbols and attitudes and stock images rather than specifically mobilized hatreds. When the mayor rants about impure races, either he or the screenplay is too decorous to mention Jews.

And this, I suppose, is my own argument with this earnest, gorgeous, at times frustrating film. Or perhaps a confession of my intellectual biases, which at least sometimes give priority to historical and political insight over matters of art and spirit. Franz Jägerstätter’s defiance of evil is moving and inspiring, and I wish I understood it better.

This is so revealing! “Their performances amount mainly to a series of radiant poses and anguished faces.” But is this not how Christian iconography works, and how painting works? Scott wants this to be a straightforward film narrative, but that’s apparently not what Malick does here (nor is it what he does in To The Wonder). The composition of the images carries more of the meaning in Malick’s movies than it does in conventional movies. I understand why this frustrates and alienates many viewers — sometimes his movies have that effect on me — but it’s what makes him such a purely cinematic director. Have you ever seen Tarkovsky’s movie Andrei Rublev? It will try your patience if you’re expecting a standard movie narrative, but if you surrender to it, and open yourself to the meaning that Tarkovsky is conveying primarily through images and composition, as distinct from the usual narrative, the radical depth of the story Tarkovsky tells invites you in.

Anyway, Scott seems especially frustrated that Malick here is not telling a familiar Holocaust story. The Christian core of the film seems completely hidden from the critic — who, admirably, admits that he just doesn’t get it. My friend Alan Jacobs, who has seen A Hidden Life, told me that it’s a masterpiece. Last night, I sent him a link to Scott’s review, and told him that I suspect this movie will also suffer, in the eyes of critics, from an ignorance of Christian theology. Jacobs wrote a response to the Scott review here. Excerpt:

Dietrich Bonhoeffer — who died nearly two years after Franz Jägerstätter, at the hands of the same regime and for the same cause — famously wrote, “When Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die.” How is it that some answer that call, even when the death demanded is in no sense metaphorical? This is something that, I think, cannot be explained, though perhaps it can be portrayed. And that is what A Hidden Life seeks to do.

Yes! These are profound mysteries. The Catholic (and even more, the Orthodox) imagination embraces the fact that life is essentially mysterious — that in the end, it cannot be fully understood by reason, but it can be grasped, and appropriated into one’s own life, through other faculties. Read Jacobs’s piece, especially the end, where he talks about why what appears from the outside to be a tragic ending is in face a pre-figuring of eternal life, and joy forever. This. Is. Christianity.

Look, this week I finished a chapter of my forthcoming book about the lessons for Christians and others living today, from the life and experience of those who lived under, and resisted, communism in Russia and Europe. This chapter focuses on the Bendas, a Catholic family in Prague. Vaclav and Kamila Benda, both professors, were the only Christians in the leadership of Charter 77, the main dissident group in Prague (Vaclav Havel was a leader of the group). Vaclav Benda served four years in jail — 1979 to 1983 — as a political prisoner. Kamila was at home raising their six children, under a totalitarian dictatorship. I write in the upcoming book:

Today, the children and grandchildren of Dr. Benda have the letters he sent to their mother from prison. They are a written testimony of how the political prisoner’s rock-solid faith helped him endure captivity. These letters are a catechism for his descendants, made vivid because they came from the pen not of a plaster saint, but a flesh-and-blood hero: the family patriarch.

“In one of his letters, he tells us about how being in prison gave him new insights into the Gospels,” says [son] Patrik. “He talks about how Jesus said in his Passion, ‘Not my will, but Thy will be done, Father.’ My dad’s letter shows how he believed that he was giving testimony by suffering persecution. This helped us all to understand the example of the Lord.”

“Dad believed that even though things were bad, and he was suffering, and that he didn’t see positive consequences from his actions, that there is a good God who will eventually win the battle,” adds Marketa, one of the Benda daughters. “God will eventually win, even though I may not see it in my life. So my suffering is not meaningless, because I am part of a greater battle that will be victorious in the end. That is what our father showed us by his life.”

“But father believed that the Communists would fall, and that he would live to see it happen,” says Patrik.

“That’s true,” says Kamila. “But he also had the conviction that to destroy the Communist regime was his mission in life. He was always talking with God and asking what is the right way. He always struggled to see the right values, and to live up to them.”

“This is something very important about my father,” says Marketa. “He believed that is was accountable before God, not before people. It didn’t matter to him when other people didn’t understand why he did the things he did. He acted in the sight of God. And you know, the Bible gave him strength, because it is full of stories of the prophets and others going beyond the border of what was comprehensible or understandable to people, for the sake of obeying the Lord.”

You see? Vaclav Benda believed that ultimately, good would triumph. Most of his fellow resisters did not expect communism to end in their lifetimes, though. That was all beside the point. For Vaclav Benda, and for the wife and children he left behind, the point was to remain faithful to God, come what may. The imprisoned professor and his Catholic family at home knew that their father was doing the only thing a faithful Christian can do, and that because of his fidelity, even if it cost him his own life, he would become an heir to the everlasting Kingdom in the next life. This is why his sacrifice had meaning in their eyes, and in his own eyes.

At one point during his imprisonment, the communists offered to release Dr. Benda if he would agree to leave Czechoslovakia with his wife and children, and never return. He thought about doing it. Who would have blamed him? He would get out of jail, the trial of his family — impoverished, fatherless, and socially marginalized — would be over, and his kids would enjoy a future of liberty and relative material prosperity in the West. Had he taken the deal, nobody could have blamed him. From my forthcoming book:

Kamila once received a letter from her husband in prison, in which he said that the government was talking about the possibility of setting him free early if he agreed to emigrate with his family to the West.

“I wrote back to tell him no, that he would be better off staying in prison to fight for what we believe is true,” she tells me.

Think of it: this woman was raising six children alone, in a communist totalitarian state. But she affirmed by her own willingness to sacrifice – and to sacrifice a materially more comfortable and politically free life for her children – for the greater good.

Which is to say, for God.

Of course the Bendas hoped that their family’s sacrifice would bring about political change. But that was not the main reason they gave themselves over to it. They did it because — well, watch the trailer for A Hidden Life below. Franz Jägerstätter’s basic reason was also theirs: the totalitarian state demanded a sacrifice that a true servant of Christ could not make. Somebody ought to make a movie of that family’s incredible story.

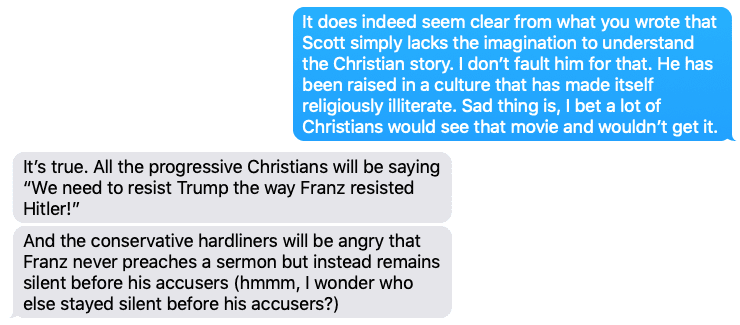

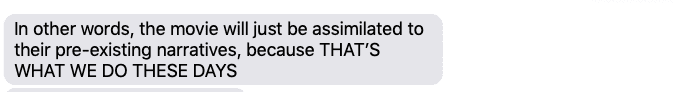

Alan Jacobs and I were texting this morning. I quote from that exchange with his permission. That’s me in blue:

Yes. The eyes of secular film critics aren’t the only ones blinded by modernity and its passions.

Below, the trailer for A Hidden Life. I am agonizing that it is not playing anywhere near me this weekend. It might be playing near you. If so, and you are interested in the subject matter, please go see it, and come back to tell us what you think: