Evangelical Dislikes ‘Live Not By Lies’

The first negative review of Live Not By Lies (that I’ve seen) comes from Trevin Wax of The Gospel Coalition, a website for conservative (ish) Evangelical types. Here’s a link to it. It’s an odd review, in that it concedes a number of the book’s points, yet still finds it alarmist, and “not just pessimistic, but overly so.” Wax said in this book, and on this blog, “fear seems too often to drive [Dreher’s] analysis.” I’m going to try to answer these criticisms. I should say that I know Trevin a little bit, and he’s a serious Christian and a genuinely nice guy. This disagreement between us on the content of my book is not personal, but professional. I think he’s quite wrong, but please dismiss any thought that in rebutting his review, that I am criticizing his character. That assumption used to be a given, but these days, alas, it needs saying.

He’s right that fear drives much of my cultural analysis — but he says it like that’s a bad thing. If you are living in Oregon, and you see wildfire cresting the hill behind your town, then fear is an appropriate reaction. It should incite you to make plans to deal with the crisis to save your life and the lives of those in your care. A fear that paralyzes is certainly to be shunned — but a fear that catalyzes is the rational response, one that can save our life.

I am trying to instill the rational kind of fear into my readers. I believe one of the greatest enemies of the church in this time and place is the middle-class complacency that everything is going to be okay if we just sit still and wait this out. This was more or less the viewpoint of some of the Slovak Catholic bishops in the 1940s, when Father Tomislav Kolakovic was organizing students to prepare for Christian resistance to the communism he foresaw overtaking their country after World War II. They thought he was an alarmist. Well, he was alarmed, that’s for sure — and thank God for it, because as I write in Live Not By Lies, that priest really did see what was coming, and the network of believers that he set up became the underground church after the communist government clamped down on all the priests and bishops.

My argument in this book is that we are facing a similar situation in the US at the present time, and that we should listen to the immigrants who grew up under communism when they express their alarm at what they’re seeing happen right here in America. From the book:

Reflecting on the speed with which utopian dreams turned into a grisly nightmare, Solzhenitsyn observed:

If the intellectuals in the plays of Chekhov who spent all their time guessing what would happen in twenty, thirty, or forty years had been told that in forty years interrogation by torture would be practiced in Russia; that prisoners would have their skulls squeezed within iron rings, that a human being would be lowered into an acid bath; that they would be trussed up naked to be bitten by ants and bedbugs; that a ramrod heated over a primus stove would be thrust up their anal canal (the “secret brand”); that a man’s genitals would be slowly crushed beneath the toe of a jackboot; and that, in the luckiest possible circumstances, prisoners would be tortured by being kept from sleeping for a week, by thirst, and by being beaten to a bloody pulp, not one of Chekhov’s plays would have gotten to its end because all the heroes would have gone off to insane asylums.

It wasn’t just the tsarists who didn’t see it coming but also the country’s leading liberal minds. It was simply beyond their ability to conceive.

I can see why passages like that would be upsetting to American Christians, but we need to be shaken out of our unjustified confidence. Things can go very bad, very quickly, once a social order comes unmoored, and fanatics take control.

To be fair to Wax, he says it’s not my pessimism that puts him off:

It’s not the pessimism I have a problem with. In fact, some of the writers I’ve read in depth (MacIntyre, Rieff, Lasch) can be categorized as pessimistic in their overall outlook. It’s the sense of hopelessness that suffuses Dreher’s pessimistic take, something that at times feels at odds with the fine principles and wise practices he recommends.

Well, this could be an aesthetic error that turns into a moral error. I fully concede that when writing in the prophetic mode, I can be so strong that it eludes readers who don’t know me that I am actually, in person, a fairly easygoing guy. In fact, I’ve thought that for my next book, I need to figure out how to convey the hope that keeps me going, and happy, in the face of dire challenges. Nevertheless, I wouldn’t have written Live Not By Lies if I didn’t think that there was reason to hope — not to be optimistic, but to hope. This comes into focus in the final chapter, when I write about the young Slovak photographer Timo Krizka, whose grandfather, a Greek Catholic priest (Greek Catholic clergy can marry), had been forced out of the priesthood because he refused to obey the government’s orders:

Several years ago, Križka set out to honor his ancestor’s sacrifice by interviewing and photographing the still-living Slovak survivors of communist persecution, including original members of Father Kolaković’s fellowship, the Family. As he made his rounds around his country, Križka was shaken up not by the stories of suffering he heard—these he expected—but by the intense inner peace radiating from these elderly believers.

These men and women had been around Križka’s age when they had everything taken from them but their faith in God. And yet, over and over, they told their young visitor that in prison they found inner liberation through suffering. One Christian, separated from his wife and five children and cast into solitary confinement, testified that he had moments then that were “like paradise.”

“It seemed that the less they were able to change the world around them, the stronger they had become,” Križka tells me. “These people completely changed my understanding of freedom. My project changed from looking for victims to finding heroes. I stopped building a monument to the unjust past. I began to look for a message for us, the free people.”

I don’t want to spoil the book’s ending, but it has to do with the paradox that the poorer and more restrained these Christians were by circumstances, the greater their joy had been. Krizka finally realized that all his freedom, and all his worldly success as an artist who grew up in the postcommunist era, had enabled his anxieties and desires to establish a tyranny over his imagination. I know, this is not a romp-through-the-bluebonnets epiphany, but it’s real, and it’s going to have to be the thing that gets faithful Christians through the hardships to come.

And that’s because the totalitarianism coming at us is going to be not Orwellian, but Huxleyan. It’s not going to be about inflicting terror and pain, but rather about managing status and pleasure. This is what makes the emerging totalitarianism here different from what the captive peoples of Russia and Eastern Europe endured. As I write:

Križka discovered a subtle but immensely important truth: We ourselves are the ultimate rulers of our consciences. Hard totalitarianism depends on terrorizing us into surrendering our free consciences; soft totalitarianism uses fear as well, but mostly it bewitches us with therapeutic promises of entertainment, pleasure, and comfort—including, in the phrase of Mustapha Mond, Huxley’s great dictator, “Christianity without tears.”

But truth cannot be separated from tears. To live in truth requires accepting suffering. In Brave New World, Mond appeals to John the Savage to leave his wild life in the woods and return to the comforts of civilization. The prophetic savage refuses the temptation.

“But I don’t want comfort. I want God, I want poetry, I want real danger, I want freedom, I want goodness. I want sin.”

“In fact,” said Mustapha Mond, “you’re claiming the right to be unhappy.”

“All right then,” said the Savage defiantly, “I’m claiming the right to be unhappy.”

This is the cost of liberty. This is what it means to live in truth. There is no other way. There is no escape from the struggle. The price of liberty is eternal vigilance—first of all, over our own hearts.

We have to claim the right to be unhappy — otherwise, there is no joy. Maybe Wax didn’t understand that point, or maybe I didn’t articulate it well. But there it is.

Wax seems to believe that he has caught me out on a contradiction: I cite the Soviet experience as a warning for what’s coming here, yet I keep saying that we’re not going to have Stalinism 2.0. That’s actually not a contradiction, though: as I make clear, Orwell and Huxley wrote about very different totalitarianisms. Orwell’s was realized in the USSR; I believe that what we are building in the West will more closely resemble Huxley’s. Wax writes:

So, on the one hand, Dreher worries we’re moving quickly toward totalitarianism like that of the Soviets, but on the other hand, it must be a soft totalitarianism, because the signs are all different, and the trajectory doesn’t follow. Are we ripe for revolution or not? “The parallels between a declining United States and prerevolutionary Russia are not exact, but they are unnervingly close,” he writes. Close in a few key ways, but radically different in others, as he himself must admit.

Um, yeah. That’s one of the main themes of the book. We really are undergoing a revolutionary moment, but this is hidden from many of us because we’re not faced with Bolshevik mobs rampaging through the streets. This is a very bourgeois revolution. Wax appears to believe he has found a contradiction in my narrative, but he has in fact discovered one of its fundamental points.

Strangely for someone who believes the book is alarmist, Wax credits its analysis of threats from the left. But it bothers him that I don’t “on the other hand” it with threats from the right:

My point isn’t that Dreher is wrong to warn against cultural currents that may sweep us into soft totalitarianism. I only wish he had explored how this tendency toward soft totalitarianism could wind up being as much a feature of a nationalist surge from the far right as it could the elitist “top down” from the far left. I understand why Dreher prioritizes the threat from the far left more than the far right—the left is embedded in various institutions that have traditionally wielded enormous power. But as Yuval Levin and other cultural observers have pointed out, these institutions have lost much of their power and credibility, which may leave us vulnerable to surges of revolutionary fervor from surprisingly unexpected directions.

Well, hang on. First, this is far, far too dismissive of the power of institutions in American life. It is certainly the case that the power of institutions is diminished. But it is also true that they are the gateways to power in American life. As I write in the book, the sociologist James Davison Hunter has warned that cultural change always begins through networks of elites. News and entertainment media, academia, and major corporations are already pumping out the pseudo-religious ideology of “social justice” into the minds of the American people — and if you dissent from it, you will increasingly find yourself shut off from participating in the mainstream of economic and cultural life. So much of Live Not By Lies is dedicated to explaining how this works that I find it weird that Wax, in his review, glosses over this.

More to the point, Wax is simply wrong to say that there is a parallel totalitarian threat from the right. There is an important difference between totalitarianism and authoritarianism. The nationalist-populist right, at its worst, promises authoritarianism. The left, by contrast, is totalitarian in its aims. From Live Not By Lies:

Today’s survivors of Soviet communism are, in their way, our own Kolakovićes, warning us of a coming totalitarianism—a form of government that combines political authoritarianism with an ideology that seeks to control all aspects of life. This totalitarianism won’t look like the USSR’s. It’s not establishing itself through “hard” means like armed revolution, or enforcing itself with gulags. Rather, it exercises control, at least initially, in soft forms. This totalitarianism is therapeutic. It masks its hatred of dissenters from its utopian ideology in the guise of helping and healing.

To grasp the threat of totalitarianism, it’s important to understand the difference between it and simple authoritarianism. Authoritarianism is what you have when the state monopolizes political control. That is mere dictatorship—bad, certainly, but totalitarianism is much worse. According to Hannah Arendt, the foremost scholar of totalitarianism, a totalitarian society is one in which an ideology seeks to displace all prior traditions and institutions, with the goal of bringing all aspects of society under control of that ideology. A totalitarian state is one that aspires to nothing less than defining and controlling reality. Truth is whatever the rulers decide it is. As Arendt has written, wherever totalitarianism has ruled, “[I]t has begun to destroy the essence of man.”

As part of its quest to define reality, a totalitarian state seeks not just to control your actions but also your thoughts and emotions. The ideal subject of a totalitarian state is someone who has learned to love Big Brother.

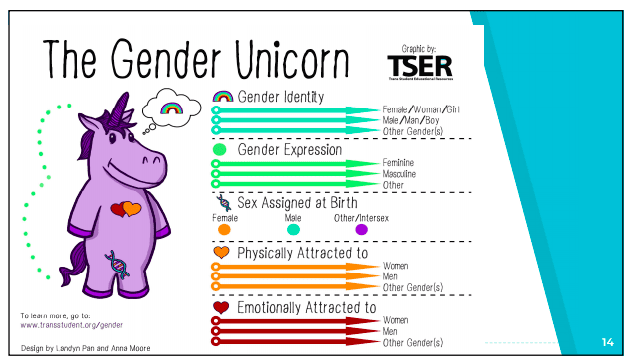

Whatever criticism you might make of, say, Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orban, or the Law & Justice government in Poland, they do not have the slightest interest in making anybody “love Big Brother” (our equivalent would be “fly the Pride flag,” “affirm Critical Race Theory,” etc.). The left does. Authoritarianism only demands control over the political space, but totalitarianism wants to “destroy the essence of man.” If you don’t think that this kind of thing, which is common in LGBT training in schools and among professionals (a reader sent this from a legal seminar he took), is destroying the essence of man, then you are not understanding the revolutionary moment upon us:

Authoritarian governments may have their problems, but they’re not trying to destroy the essence of man.

Finally, Wax concludes:

I’m not as sure as Dreher that these days are just around the corner for us; neither am I as confident that they’ll necessarily come from the socialist left rather than the populist right, since history is full of surprises, and future trends can be upended in cataclysmic events that almost no one foresees. I also believe that such resistance can be only marshaled and sustained if accompanied by a deep and abiding sense of joy. Most of my family members and friends who persevered as dissidents under communism were marked by a profound joyfulness. The joy of the Lord (even if not evident in this book) must mark any successful resistance.

OK, he’s not as sure as I am. Why not? I have laid out a meticulous case for why I believe we are in real trouble, including devoting a lot of space to Hannah Arendt’s analysis of a pre-totalitarian culture, to a deep discussion of the way theories of “social justice” now going mainstream (even now tearing apart churches) work like acid on Christian assumptions, and a long discussion of how the expanding of data-gathering technology into every aspect of our lives sets us up for manipulation and control, along the lines of China’s surveillance-based social credit system. Wax ignores all of this. I would have loved to have known why he thought my arguments were wrong. But he doesn’t really engage them. The reviewer just seems to have found it all too depressing to think about.

Well, yeah, it is depressing to think about. But that doesn’t make it untrue.

Nor does the fact that right-wingers have created totalitarianisms in the past (e.g., Mussolini’s Italy, Hitler’s Germany) mean that they are on the verge of doing the same today. Sure, we have to be vigilant against that, but again, I have made an actual argument for why the big threat here and now comes from the left. I have never been a fan of Donald Trump, did not vote for him in 2016, and think he’s been a lousy president for the most part. But Donald Trump is not pumping this revolutionary poison through the American body politic. It’s not going to be the Trump Administration that comes after the traditional Christian institutions that won’t accept the new ideology. It’s not schools and universities of the right who are training white children like mine and Wax’s to despise themselves because of the color of their skin, and to question whether or not they are male or female. It’s not right-wing capitalists like tech giants and major banks who are busily deplatforming dissenters, and who are working to make it harder for dissenters to participate in the economy. There are no right-wing mobs at universities driving left-wing professors and speakers off campus. Alt-right Millennials and Zoomers embedded inside major media institutions, like The New York Times and the Washington Post, are not driving the content of the coverage, and driving out senior editors who refuse to toe the ideological line. It’s not right-wingers within professional associations that are working now to make it impossible to be credentialed if you don’t affirm certain woke claims. And so forth.

All of these things are happening on the left, right now. But hey, maybe they will start happening on the right too. Ya never know. I think this is whatabouttery serving as a strategy to avoid making hard choices, but then, as an alarmist, I would say that, wouldn’t I?

UPDATE: A reader points out that Wax’s review reminds him of the “Neutral World” classification that Aaron Renn articulated three years ago in this piece about American Evangelicalism. In Renn’s view, “Neutral World” presupposes that Christianity exists in a broader culture that is neither positively nor negatively disposed towards it. Neutral World Christians believe in “cultural engagement,” and take their cues from secular elites, says Renn. Here is the key excerpt from Renn’s essay, which he published in 2017 (and in which he criticized my Benedict Option a bit, but credited it with at least dealing with reality):

My initial thought is that as soon as being known as a Christian would incur a material social penalty, which I anticipated happening soon, there would be a mass abandonment of the faith by the megachurch crowd, etc.

I was wrong about that. What happened instead is that the neutral world Evangelicals largely decided to follow the response of the traditional mainline denominations before them in embracing the world and focusing on the social gospel. In other words, they decided to sign on with the winning team.

The average neutral world Christian leader – and that’s a lot of the high profile ones other than the remaining religious righters, ones who have a more dominant role than ever thanks to the internet – talks obsessively about two topics today: refugees (immigrants) and racism. They combine that with angry, militant anti-Trump politics. These are not just expounded as internal to the church (e.g., helping the actual refugee family on your block), but explicitly in a social reform register (changing legacy culture and government policy).

I’m not going to argue that they are wrong are those points. But it’s notable how selective these folks were in picking topics to talk about. They seem to have landed on causes where they are 100% in agreement with the elite secular consensus.

It’s amazing how loud and publicly chest thumping they are on these topics while never saying anything that would get them uninvited from a Manhattan cocktail hour. They are very party line. (Since I mentioned Keller earlier I’ll point out he’s been somewhat different. He pointedly refused to take a position on the election, for example, saying that as a pastor he had to stick to the Bible and not give political opinions. And angry screeds aren’t his style).

I won’t speculate on their motives, but it’s very clear that neutral world leaders have a lot to lose. Unlike Jerry Falwell, who never had secular cachet and lived in the sticks, these guys enjoy artisanal cheese, microbrews, and pour over coffees in Brooklyn. They’ve had bylines in the New York Times and Washington Post. They get prime speaking gigs at the Q conference and elsewhere. A number of them have big donors to worry about. And if all of a sudden they lost the ability to engage with the culture they explicitly affirmed as valuable, it would a painful blow. For example, to accept Dreher’s Benedict Option argument they’d have to admit that the entire foundation of their current way of doing business no longer works. Not many people are interested in hearing that.

The neutral world Christians – and again that seems to be much of Evangelical leadership today – are in a tough spot when it comes to adjusting to the negative world. The move from positive to neutral world brought an increase in mainstream social status (think Tim Keller vs. Pat Robertson), but the move to a negative world will involve a loss of status. Let’s be honest, that’s not palatable to most. Hence we see a shift hard to the left and into very public synchronization with secular pieties. That’s not everybody in Evangelical leadership, but it’s a lot of them. Many of those who haven’t are older and long time political conservatives without a next generation of followers who think like them. (Political conservatism is also dying, incidentally).

Believe me, I get it. Always remember the Law of Projection. What you see in others is what’s present in yourself. I live in NYC. I love going to the opera. I’m into all that stuff. My urban work is a version of neutral world strategy I called “policy not politics.” I focus almost exclusively on local policies, which are far way from the world of national politics. I studiously avoid giving my opinion on things like Obamacare, not just because I’m not an expert on it, but also because it will just alienate people (regardless of my position) gratuitously. I try to be completely evenhanded in criticisms of Republicans and Democrats. I’m in the mainstream media. My personality is also not really oriented towards high-conflict environments. I prefer being generally liked. I’ve got a lot to lose. Changing that approach would be really hard.

But the reality is even in my secular urban work the ground is eroding under my feet. Everything is becoming hyperpolitical, whether I want it to be or not or whether it should be or not. I’m going to end up in a higher conflict mode whether I want to or not. Just like what happened to Tim Keller at Princeton. Buckle up.

People are going to be forced to make choices, across a wide spectrum of domains. I’m afraid current trends indicate that Christian leaders are going to make the wrong ones. We already know from the past that social gospel style Christianity is a gateway to apostasy. That’s where the trend is heading here.

I was speaking with one pastor who is a national council member of the Gospel Coalition. He’s a classic neutral worlder who strongly disapproves of Trump. But he notes that the Millennials in his congregation are in effect Biblically illiterate and have a definition of God’s justice that is taken from secular leftist politics. They did not, for example, see anything at all problematic about Hillary Clinton and her views. A generation or so from now when these people are the leaders, they won’t be people keeping unpopular positions to themselves. They won’t have any unpopular positions to hide. They will be completely assimilated to the world. Only their ethics will no longer be Hillary’s, but the new fashion du jour.

Rather than a mass blowout then, Evangelicalism would thus die from a slow bleed, much as the mainlines and the Church of England did before them. Indeed, today’s Evangelicals are retracing the steps of the mainlines. The parallels with the late 19th/early 20th centuries are there and should be studied. Back then, for example, virtually all of the sophisticated intellectual and cultural types – the cultural engagers of their day – sided with the world and became today’s liberal mainlines. Many of the ones who remained orthodox, like Gresham Machen, paid a huge price for doing so – largely inflicted by their erstwhile brethren who assimilated. As it turns out, intellectuals are very easy to co-opt with a few trinkets.

It looks like it’s happening again. Almost every Evangelical institution I know is explicitly reformulating itself around secular social gospel principles, even if they wouldn’t use those words to describe it. There will be residual beliefs in place, but over time they could dissipate to nothing. (Remember, the liberal mainlines didn’t go from A to B overnight. It was a long process. For example, earlier this year I read a book by famed early 20th century liberal preacher Henry Emerson Fosdick that contained things so reactionary that even many “conservative” pastors today would be unwilling to write them).

Read it all. That was a good catch by the reader. Whether he means to be or not, Trevin Wax is working from a Neutral World paradigm, but he’s living — we all are in the US — in Negative World. I expect that Live Not By Lies will be poorly received by Christians who insist that we live in Neutral World. As Renn wrote back in 2017, if we live in Negative World, then Christians like him (and like me!) who enjoy living in the world are going to be in for hard times. We are going to be forced to make hard choices, because the world itself will no longer give us the opportunity for neutrality. That has become as sharp and as clear as a shard of glass smashed out of a storefront window. To believe that you can avoid the difficult parts of a pessimistic argument because of its supposed joylessness, and throw some anti-Trump whatabouttery at the problem, like a handful of salt tossed over one’s shoulder for good luck, is a textbook Neutral World response.

I would have probably responded better to Wax’s review if he had flat-out rejected the book. The weird thing about it is that he seems to believe that I’m onto something real (he acknowledges that people from Romania in his circles also see the sunny skies of America darkening in a familiar way), but the fact that I don’t say it with winsomeness, and don’t say “But Trump too!”, seems to have put him off.

Eventually, though, middle-class believers like Trevin Wax — and like the author of Live Not By Lies — are going to have to make hard choices. The temptation to rationalize is going to be very, very seductive.