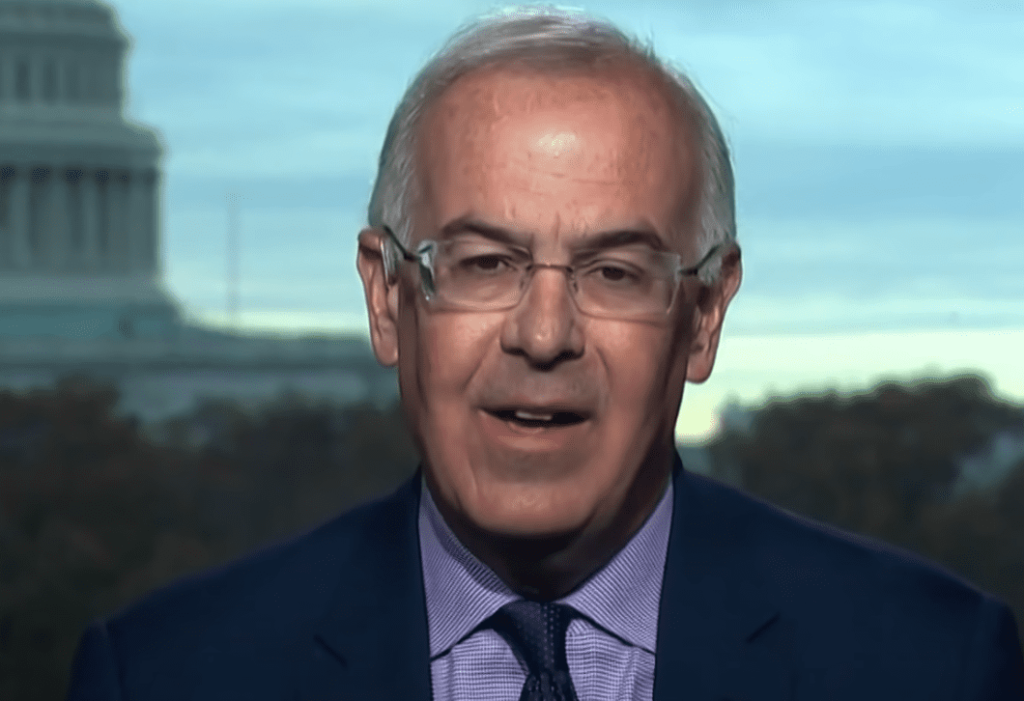

David Brooks’ Farewell To Conservatism

The only thing more tedious on the online Right than ritual denunciations of David French is ritual denunciations of David Brooks. I had intended to bypass the temptation following Brooks’s recent Atlantic essay about how he ceased to be a conservative (at least according to what passes for conservatism today), because a) it is not news that David Brooks is no longer a conservative, and b) why join the piling-on? David is an old friend, and though we no longer share many of the same political views, I am loyal to my friends, because friendship, for me, does not depend on sharing political beliefs. I despise the contemporary habit — on both the Left and the Right — of turning on one’s friends because they disappoint you politically. The truth is that David Brooks is a very kind, very thoughtful and compassionate man who has simply lost his faith in the Right. I think he is mostly (but not completely) wrong on that, but he remains my friend, and those who don’t like it can go to Hell (or worse, to San Francisco).

But reading Ross Douthat’s weekend column on “what the New Right sees” that the rest of the political class does not made me reconsider. Ross cites David Brooks’s take on the Nat Con conference, and an essay by Sam Adler-Bell in The New Republic. Excerpt from Douthat’s column:

The essays emphasize the ways in which the newer, younger right is ill at ease in contemporary America, its psychology defined more by alienation than the basic patriotic comfort (however threatened by Communists and liberals) that Ronald Reagan successfully embodied.

This emphasis is understandable, but there’s another way of looking at the new right’s place in American politics. Its vibe is alienated and radical, certainly — but at the same time its analysis of our situation feels more timely, more of this moment, than many alternative programs on the right or left or center.

Suppose you made a list of what each tendency in American politics considers our biggest challenges right now. For the new right, the list might look something like this.

Abroad, the double failure of our post-9/11 nation-building efforts and our open door to China, which requires either a recalibration to contain the Chinese regime or else a general pullback from an overextended empire.

At home, the threat to liberty from Silicon Valley monopolies enforcing progressive orthodoxy and the threat to human happiness from the addictive nature of social media, online pornography and online life in general. The collapse of birthrates, the dissolution of institutional religion and the decline of bourgeois normalcy, manifest in the younger generation’s failure to mate, to marry, raise families. The post-1960s “great stagnation” in both living standards and technological innovation. The costs of cultural libertarianism, the increase in unhappiness and high rates of depression and addiction in a more individualistic society.

Then finally, the way in which the technocratic response to the pandemic, the retreat to a virtual life suited only to a “laptop class” (and maybe not even to them), may make these problems worse.

Now, you can critique this list and doubt its diagnoses. But still, if you look at reality through the new right’s alienated vision, you may see the strange world of 2021 more clearly than through other eyes.

Douthat goes on:

But still, if you asked which worldview has organized itself primarily around things that have changed in the world since 1999, I don’t think you’d pick progressivism.

So, to Brooks’s essay. To be clear, he doesn’t distance himself from conservatism per se, only from the contemporary American Right. He begins by talking about how as a young man, he read himself out of the Left:

I started reading any writer on conservatism whose book I could get my hands on—Willmoore Kendall, Peter Viereck, Shirley Robin Letwin. I can only describe what happened next as a love affair. I was enchanted by their way of looking at the world. In conservatism I found not a mere alternative policy agenda, but a deeper and more resonant account of human nature, a more comprehensive understanding of wisdom, an inspiring description of the highest ethical life and the nurturing community.

What passes for “conservatism” now, however, is nearly the opposite of the Burkean conservatism I encountered then. Today, what passes for the worldview of “the right” is a set of resentful animosities, a partisan attachment to Donald Trump or Tucker Carlson, a sort of mental brutalism. The rich philosophical perspective that dazzled me then has been reduced to Fox News and voter suppression.

I recently went back and reread the yellowing conservatism books that I have lugged around with me over the decades. I wondered whether I’d be embarrassed or ashamed of them, knowing what conservatism has devolved into. I have to tell you that I wasn’t embarrassed; I was enthralled all over again, and I came away thinking that conservatism is truer and more profound than ever—and that to be a conservative today, you have to oppose much of what the Republican Party has come to stand for.

More:

Another camp, which we associate with the Scottish or British Enlightenment of David Hume and Adam Smith, did not believe that human reason is powerful enough to control human selfishness; most of the time our reason merely rationalizes our selfishness. They did not believe that individual reason is powerful enough even to comprehend the world around us, let alone enable leaders to engineer society from the top down. “We are afraid to put men to live and trade each on his own private stock of reason, because we suspect that this stock in each man is small,” Burke wrote in Reflections on the Revolution in France.

This is one of the core conservative principles: epistemological modesty, or humility in the face of what we don’t know about a complex world, and a conviction that social change should be steady but cautious and incremental. Down the centuries, conservatives have always stood against the arrogance of those who believe they have the ability to plan history: the French revolutionaries who thought they could destroy a society and rebuild it from scratch, but who ended up with the guillotine; the Russian and Chinese Communists who tried to create a centrally controlled society, but who ended up with the gulag and the Cultural Revolution; the Western government planners who thought they could fine-tune an economy from the top, but who ended up with stagflation and sclerosis; the European elites who thought they could unify their continent by administrative fiat and arrogate power to unelected technocrats in Brussels, but who ended up with a monetary crisis and populist backlash.

And:

Burkean conservatism inspired me because its social vision was not just about laws, budgets, and technocratic plans; its vision was about soulcraft, about how we build institutions that produce good citizens—people who are moderate in their zeal, sympathetic to the marginalized, reliable in their diligence, and willing to sacrifice the private interest for public good. Conservatism resonated with me because it recognized that culture is more important than the state in driving history.

Well, so far I agree with most of this, which is why I think of myself as more or less a Burkean conservative. To the extent that I hate this or that manifestation of the contemporary Right, it’s because I am either a traditional Christian or a Burkean conservative. This passage is really insightful about the particular nature of American conservatism:

American conservatism descends from Burkean conservatism, but is hopped up on steroids and adrenaline. Three features set our conservatism apart from the British and continental kinds. First, the American Revolution. Because that war was fought partly on behalf of abstract liberal ideals and universal principles, the tradition that American conservatism seeks to preserve is liberal. Second, while Burkean conservatism puts a lot of emphasis on stable communities, America, as a nation of immigrants and pioneers, has always emphasized freedom, social mobility, the Horatio Alger myth—the idea that it is possible to transform your condition through hard work. Finally, American conservatives have been more unabashedly devoted to capitalism—and to entrepreneurialism and to business generally—than conservatives almost anywhere else. Perpetual dynamism and creative destruction are big parts of the American tradition that conservatism defends.

If you look at the American conservative tradition—which I would say begins with the capitalist part of Hamilton and the localist part of Jefferson; extends through the Whig Party and Abraham Lincoln to Theodore Roosevelt; continues with Eisenhower, Goldwater, and Reagan; and ends with Mitt Romney’s 2012 presidential campaign—you don’t see people trying to revert to some past glory. Rather, they are attracted to innovation and novelty, smitten with the excitement of new technologies—from Hamilton’s pro-growth industrial policy to Lincoln’s railroad legislation to Reagan’s “Star Wars” defense system.

A painful truth that conservatives of my ilk have to face: the American conservative tradition is fundamentally liberal, in the sense Brooks discusses here. The nation itself was born in a rejection of Throne-and-Altar conservatism, in favor of classical liberalism. We Americans are a lot like what post-Vatican II Catholics are coming to be: a people whose cultural memories are of a “tradition” that is anti-traditional.

How did Brooks-approved conservatism turn into Trumpism? According to David Brooks:

The reasons conservatism devolved into Trumpism are many. First, race. Conservatism makes sense only when it is trying to preserve social conditions that are basically healthy. America’s racial arrangements are fundamentally unjust. To be conservative on racial matters is a moral crime. American conservatives never wrapped their mind around this.

Stop right there. If Brooks was writing this in the 1960s or 1970s, it would make sense. Today, though, “to be conservative on racial matters” is to defend the Martin Luther King vision of people judged not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. The people calling for heightened racial consciousness and animosity, and for institutions that judge people by the color of their skin, are liberals and progressives.

Brooks devotes a single paragraph to the role economics played in the transformation — an astonishing oversight for so careful a thinker. David and I are roughly the same age. Over our lifetimes, we have seen dramatic changes in the American landscape because of trade liberalization and globalization — a process that has been blessed by both the mainstream Right and the mainstream Left. Our children face a world of far more economic and personal insecurity because of these changes. When you are considering why young people are more radically Left or radically Right, we can’t ignore what economics has done here.

(But we old people have to also point out, firmly, that the world that produced Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher was totally unsustainable. I sent my college-student son the other day a chart showing that in 1980s, US inflation was 14 percent. I reminded him that the country had been macerating in economic misery for years. It was far worse in Britain. If you want to know how Reagan and Thatcher emerged, economics played a big part in it.)

More Brooks:

But perhaps the biggest reason for conservatism’s decay into Trumpism was spiritual. The British and American strains of conservatism were built on a foundation of national confidence. If Britain was a tiny island nation that once bestrode the world, “nothing in all history had ever succeeded like America, and every American knew it,” as the historian Henry Steele Commager put it in 1950. For centuries, American and British conservatives were grateful to have inherited such glorious legacies, knew that there were sacred things to be preserved in each national tradition, and understood that social change had to unfold within the existing guardrails of what already was.

By 2016, that confidence was in tatters. Communities were falling apart, families were breaking up, America was fragmenting. Whole regions had been left behind, and many elite institutions had shifted sharply left and driven conservatives from their ranks. Social media had instigated a brutal war of all against all, social trust was cratering, and the leadership class was growing more isolated, imperious, and condescending. “Morning in America” had given way to “American carnage” and a sense of perpetual threat.

Look, my hostility to Trumpism is well known. I don’t need to recapitulate it here. I think he is a disgraceful character, and in no way a conservative. The one thing he got right, though — and I think he stumbled into it — is that the system was rotten, and had to change. Brooks characterizes the contemporary Right like this:

On the right, especially among the young, the populist and nationalist forces are rising. All of life is seen as an incessant class struggle between oligarchic elites and the common volk. History is a culture-war death match. Today’s mass-market, pre-Enlightenment authoritarianism is not grateful for the inherited order but sees menace pervading it: You’ve been cheated. The system is rigged against you. Good people are dupes. Conspiracists are trying to screw you. Expertise is bogus. Doom is just around the corner. I alone can save us.

I share some of his anger at the worst aspects of the New Right. QAnon is a cancer. Too many of us are satisfied with the emotional pleasure of owning the libs — that is, we are satisfied to indulge our hatreds instead of building something new and better. And we are too quick to blame others for all our problems than to look inside ourselves.

That said, I think my friend is blind to a lot of what is happening in our country, and what has happened.

All those experts, especially on the Right, who said that we had to go to war against Iraq? They were wrong. They were catastrophically wrong, in ways that really, really mattered. All the experts in the 1990s — the Republicans, and the Clinton Democrats — who said that Wall Street should be unchained to make us all rich? They were catastrophically wrong, as the 2008 crash revealed. All the great generals we had that kept telling us that we were turning the corner in Afghanistan? We now know, via the Afghanistan Papers, that they lied their asses off, and spent American blood and American treasure in a war they knew we could not win.

And now the experts are telling us that our sons may be daughters, and our daughters sons — and if we disagree we are bigots who are driving our children to suicide. They are telling us that our country was built on racism, and that there is nothing good in its history that negates the taint. Better pull down those statues now. Woke ideology has now conquered all the high ground in American institutional life, such that if you dissent from any of it, you are putting your livelihood in danger. They really are out to disempower and to punish dissenters. This is the world that the experts of our ruling class have brought to us. And we are pre-Enlightenment savages for thinking ill of this arrangement? No, I don’t believe that at all. David says he accepts the Burkean view that our institutions matter in terms of “soulcraft”. How on earth can he believe that our aggressively woke institutions, the ones that make dissent impossible, are making America and its people better?

David comes out as a Democrat here:

I’m content, as my hero Isaiah Berlin put it, to plant myself instead on the rightward edge of the leftward tendency—in the more promising soil of the moderate wing of the Democratic Party. If its progressive wing sometimes seems to have learned nothing from the failures of government and to promote cultural stances that divide Americans, at least the party as a whole knows what year it is. In 1980, the core problem of the age was statism, in the form of communism abroad and sclerotic, dynamism-sapping bureaucracies at home. In 2021, the core threat is social decay. The danger we should be most concerned with lies in family and community breakdown, which leaves teenagers adrift and depressed, adults addicted and isolated. It lies in poisonous levels of social distrust, in deepening economic and persisting racial disparities that undermine the very goodness of America—in political tribalism that makes government impossible.

I strongly disagree that the Democratic Party “as a whole knows what year it is.” As Douthat avers, the Democrats today behave as if they are the feisty underdogs facing down a racist, bigoted behemoth that controls all of American life — when in fact the cultural Left is thoroughly dominant. Brooks published this essay in a magazine that is the voice of the Establishment, and which regularly publishes the ideological expectorations of that racist midwit Ibram X. Kendi, but where not even the anti-Trump libertarian Kevin D. Williamson could find a place, because the oh-so-tolerant Atlantic newsroom refused to have him.

Furthermore, these same progressive elites control the most important gatekeeping institutions of our society. At Princeton, the mob is trying to force out Prof. Joshua Katz, a classical liberal, because he objects to the racist overhaul of the university’s pedagogy, and to left-wing, race-based intimidation on campus. The stories like that are legion. The message could not possibly be clearer: that if you aspire to join the establishment in the United States, you must sign off on ideological progressivism.

This same establishment is busy both destroying the US Armed Forces with this poisonous woke ideology, which demonizes the kinds of Americans who are the most likely to go into the military, and seeming eager to get the US into another war, this time with Russia over Ukraine.

Finally, our Silicon Valley overlords are busy working to surveil us and use the power of technology to drive people on the Right out of the marketplace of ideas and of goods.

All of this is happening right now — but it all escapes the notice of David Brooks. These are not invented bogeymen. They are real. But if you don’t see them as negative phenomena, you will naturally think that the Right is concerned about nothing.

I’m not trying to be a Whataboutist here. Brooks is not entirely wrong about the state of the Right today. Do I think Donald Trump, and what he represents, is the answer to this crisis? I do not. But you cannot blame people for reaching out to somebody, anybody, who seems to understand their fear and anxiety. As I’ve said in this space many times, I hope to see a Republican politician who understands the validity of what Trump tapped into, but who can direct it to constructive ends.

That figure may or may not come, and in any case, I believe that our crisis in America cannot be solved politically, though politics are part of the answer. One more time: I do not blame my friend David Brooks for losing faith in the most influential iteration of American conservatism of our moment. I do, however, fault him for not seeing the whole picture. If he says that Donald Trump and Trumpism are not the answer to our problems, I agree with him. If he believes centrist managerial liberalism is the answer, then I strongly disagree with him, and in fact say that many of our problems were caused by the managerial class. How wokeness can be reconciled with even the 1980s version of conservatism that first captured the affections of young David Brooks is a total mystery to me.

Think of it like this: if you are a working-class white teenage boy, living in a trailer park in rural Alabama with your single mom, struggling to make it through school, and to break out of the the dysfunction and drug use you see all around you, what hope does the outside world give you? It has decided that you are what’s wrong with the world, because of your race and your sex. That little Baptist church you sometimes attend, the only one that gives you a sense that somebody loves you — it too is what’s wrong with the world, according to the people who run our society, because it promotes bigotry against LGBTs. You are pretty confident that if you go to college, you are going to find yourself in a milieu in which you are going to be expected to despise your people. The people who administer the college speak in a strange argot that you can neither understand nor master, but which you are pretty confident is meant to separate out people like you.

You have thought about going into the military, like J.D. Vance did, to get a leg up on the world. But now you’re reading and hearing that the same ideology that construes you as problematic has taken over the military. Besides, you know people in your town, and even in your family, who came back from the war in Afghanistan damaged. You know that the top generals knew a long time ago that the war was unwinnable, but they kept lying about it, to keep sending back men and women from your own community there. Why would you want to put your own life into the hands of these elites, who were never held accountable for their failure?

The poor Latino immigrant kids down the road that you go to school with, they have a lot stacked against them, but at least the power-holders in our society are on their side. The poor Asian immigrant kids at your school might think they have the power-holders on their side, but if they rise and, through their own hard work and self-discipline, qualify for places in the best universities, then these Asians will discover the truth: they too are disfavored by the power elites.

And if you think that the fix is in against you, well, there will be power elites who are prepared to tell you that you are paranoid. But you aren’t, not really. A movement that has more affection for the Acela corridor than Rust Belt is barren ground for a movement trying to plant hedges against populist radicalism.

Attentive readers of the Brooks essay will get the reference in the previous line. In his piece, Brooks writes:

A movement that has more affection for Viktor Orbán’s Hungary than for New York’s Central Park is neither conservative nor American. This is barren ground for anyone trying to plant Burkean seedlings.

Well, hold on. That’s a strange comparison — Hungary to Central Park. Nobody on the Right hates Central Park. Who can hate Central Park? The more apt comparison is to Manhattan, meaning NYC as a cultural and political entity. New York City and San Francisco are considered to be the epitome of urban liberalism. Leaving aside the basket case that is San Francisco, let’s consider New York. The city has been declining back into the Bad Old Pre-Rudy Days, as we well know. Crime is on the rise. Back in 2019, the liberal writer George Packer wrote for The Atlantic (!) a piece about how wokeness enforced from the top is ruining the city’s public schools. We could go on. Now, what is it about Viktor Orban’s Hungary that should make the Right less admiring of it than of Bill DiBlasio’s New York? I would genuinely like to know.

What is Orban trying to conserve? For one thing, he’s trying to protect his country’s sovereignty, and to defend the right of the Hungarian people to decide how to govern themselves, and not to be compelled to yield to Brussels. He’s also trying to put the state on the side of parents who would like some help in protecting their children from gender ideology. And he’s tried, with limited success, to prevent the toxic ideology of wokeness, which is destroying American higher education, from infiltrating Hungary’s universities. Finally, he understands that his people are an embattled minority in the world, with their unique language and particular culture — and is attempting to keep the sentimental humanitarianism of the EU elites from dispossessing Hungarians in their own land, as the French and the Germans are being dispossessed in their own. And he’s doing all this in a democracy, in which the people can throw him and his party out of office at the next election (and just might).

What, exactly, is un-Burkean about that? Do words mean anything?

Al Mohler writes in criticism of the Brooks essay:

David Brooks wants a conservatism of manners, not a conservatism based in eternal truths. He actually fears any movement that claims to base its principles on truth rather than manners and tradition. That includes his former colleagues at National Review. “I didn’t quite have their firm conviction that there is a transcendent, eternal moral order to the universe and that society should strive to be as consistent with it as possible,” Brooks wrote in 2007.

That explains just about everything about the strange tale of David Brooks. A lack of belief in “a transcendent, eternal moral order” as a basis for his worldview explains why Brooks thinks it quite reasonable that a man should be able to marry a man and that same-sex marriage represents “a victory for the good life.” It explains why he ignores the natural family and decries the nuclear family as a mistake, arguing for “forged families” as a communitarian alternative. His disavowal of a transcendent moral order is what explains his concerns about abortion. What caused his reconsideration of the pro-choice position? In his own words, “experience and moral sentiments.” But he ends up proposing that abortion be freely available for the first trimester. Moral sentiments aren’t enough to defend the unborn in the period when most abortions are performed.

If there is no transcendent, eternal moral order, then morality is just a process of civic negotiation and everything is up for grabs. David Brooks can affirm same-sex marriage and early-term abortion and indict the nuclear family as a mistake—and yet remain comfortable within his worldview of manners and moral sentiments. Conservatism lives or dies on the belief that we are conserving created reality and serving eternal truths. Otherwise, all that remains is custom, manners, and moral sentiment—and they are no match for the forces of progressive morality.

I conspicuously lack the pugilistic sentiment that many of my friends and colleagues on the Right have towards David Brooks, of whom I am very fond, and whom I trust would have my back if I was in a personal crisis while many people who share my views would walk away. I feel the same way about him. That said, I think Mohler is mostly correct here. Brooks, by his own admission, is not a social conservative, nor, despite his move towards religious faith in recent years, would he qualify as a religious conservative. I think that if David still lacks belief in a transcendent moral order in the cosmos, that would explain a lot about why he believes the things he does, and why he doesn’t understand why people like me believe the things that we do.

So what? Unlike so many on the Left and the Right today, David retains the ability to be able to talk to all kinds of people. In his Atlantic dispatch from Nat Con, he wrote about how he had a good time talking with conservatives around the bar there. I find that ability to be civil and open-minded as admirable as it is rare today. The man is simply wrong about some important things; he is not evil. All of us, on all sides, live to some extent within a bubble, and don’t know what we don’t know. I have more respect for people who are wrong about politics, religion, and culture, but who treat others with respect and humanity, than those who get the abstract principles right, but mistreat others.

Brooks quotes Burke here:

“Manners are of more importance than laws,” Burke wrote. “Upon them, in a great measure, the laws depend. The law touches us but here and there, and now and then. Manners are what vex or soothe, corrupt or purify, exalt or debase, barbarize or refine us, by a constant, steady, uniform, insensible operation, like that of the air we breathe in. They give their whole form and color to our lives. According to their quality, they aid morals, they supply them, or they totally destroy them.”

David and I are both writers who place a lot of stock in manners. Any well-raised Southerner, no matter what their race or social class, understands in his bones why manners are important. That said, it is all too easy to find oneself willing to tolerate the intolerable because those who object to it have rotten manners. Among we who place a high premium on manners, it is not at all difficult to judge people based on their vulgarity or lack thereof, rather than what they believe and advocate. Some of the best-mannered people in the Old South held barbarous opinions about black people, for example. Some of the best-mannered people in the contemporary North hold contemptible views of working-class white people and traditionally religious people. There is nothing about Donald Trump that I admire, or would want to see in my children’s character. I don’t want to have Donald Trump over to dinner. I would rather go over to the Brooks’s and have dinner with Barack and Michelle Obama, not because I share their politics, but because I think we could have a really good political discussion without hating on each other. But I would prefer Trump as a politician to a well-mannered liberal like Joe Biden who believes in and pushes for policies that I believe are profoundly destructive to the common good. Life is complicated.

Liberalism in 2021 is not the same as liberalism in 1991; nor is conservatism. As Burke himself wrote, states without the means to change are also without the means of their own conservation. The conservative party — the GOP — has failed to conserve much of anything. It is now changing into a party that seems at least willing to try to conserve some things. It was inevitable that right-liberals like David Brooks would move to the Democratic Party, just as it is inevitable that some Latinos will move to the GOP. This is what realignment means. I don’t know why it has upset so many people on the Right to discover that David Brooks no longer considers himself allied in any way with American conservatism. I don’t think I have ever had a conversation with him about it, but then, I didn’t have to. I read his stuff.

One more thing. I know this is going to fall on deaf ears, but I strongly encourage my fellow conservatives to be more focused in their criticism of David Brooks, and to abandon personal smears. A lot of people love to say things about his marriage that I know for a fact aren’t true, and are therefore unjust and cruel. And though I think he is way off base on his views about race in America, I also know for a fact that David has quietly done far more work in the real world to help poor minority youth than I have, or that most conservative friends of mine have (I can think of two exceptions, but only two). That doesn’t make Brooks correct in his political judgments, but it does earn him a hell of a lot of credit, I’d say. Characteristically, he is too modest to talk much about any of that, much less brag about it. But it’s real. If you want to criticize Brooks in the comments of this blog entry, stick to his ideas. I’m not going to publish personal insults against him. He’s wrong about this stuff, but he’s my friend, and I’m not going to put up with people trashing his character.