Critic or Coroner?

We all need good novels.

The Novel, Who Needs It?, by Joseph Epstein, Encounter Books, 152 pages.

The novel, having been abroad in the world for centuries, has fallen on hard times with the reading public, and everyone has a theory why. Joseph Bottum a few years ago blamed the collapse of Mainline Protestantism. Philip Roth said in 1961 that a novelist couldn’t hope to compete with the fever of real American life on the nightly news. In 2009, fifty years and 25 novels of his own later, Roth blamed short attention spans. For Jules Verne in 1902, it was the newspaper. Lionel Trilling, after the war, declared a crisis of the bourgeois imagination. It’s fascism or communism, or both. It’s the internet, it’s disenchantment, it’s the movement of history—it’s modernism, in the library, with the candlestick.

At the end of this century-long game of Clue, does Joseph Epstein have anything new to say on the topic? Well, not really.

The Novel: Who Needs It? has a lot to recommend it. It is easy to read, composed in notes of a few pages, each taking up a different aspect of the thesis that the novel “provides truths of an important kind unavailable elsewhere in literature or anywhere else.” Epstein has compiled a wonderful pile of quotations and testimonies to the power and importance of novels, what D.H. Lawrence called “the one bright book of life.”

In a short posthumous essay, Lawrence gave the classical statement in praise of the novel as a guide to human life:

In life, there is right and wrong, good and bad, all the time. But what is right in one case is wrong in another. And in the novel you see one man becoming a corpse, because of his so-called goodness, another going dead because of his so-called wickedness. Right and wrong is an instinct: but an instinct of the whole consciousness in a man, bodily, mental, spiritual at once. And only in the novel are all things given full play, or at least, they may be given full play, when we realize that life itself, and not inert safety, is the reason for living.

Epstein takes up this strain. In reading novels, we are having an experience that is at once aesthetic and deeply moral. Novels, at their best, can allow us to experience the very private humanity of the characters who populate our society and the historical, ideological, and cultural forces which shape their lives, as they do our own.

Novels make arguments to us. They say, this is how things are. Here is this man, here is his social position. How similar is it to your own? Watch him rise, watch him fall. What sort of character is he? How does he go about his day? How does he think? What causes him to struggle? Do all these add up, at the end of the book, to a happy life for him? The novel can show us ourselves and our neighbors from the inside, in great detail and for an extended period of time, and in doing so help us understand what sort of characters we ourselves might be, and what sort we might want to become instead.

The big questions—you’re familiar, stuff like God and goodness, love and loathing, virtue and vice, whatever stylish alliterations you prefer—don’t work themselves out for us on paper before we get out of bed in the morning. We have philosophers to help us through the sharp points of speculative quandaries, but that sort of thinking falls flat when the particulars of life pick up, when the questions in front of us descend from “Thou shall not” to the situations in which we actually confront for ourselves.

Epstein emphasizes that the novel sets itself apart from other kinds of art by its “respect for the complexity of experience,” the detail with which it can render human life, which more often resembles a mess of contradictions than a finely ordered theoretical demonstration. That is its chief strength, and what recommends the reading of novels to us as more than an aesthetic diversion: “The novel deals with individuals, the specific details of their lives, and in a way that marked a distinct departure from the classical literary treatment exhibited by Homeric heroes, Sophoclean tragic figures, Dantesque types.”

Why is it, then, that something this big and important seems to be always on its last legs? Epstein himself acknowledges that the “Death of The Novel” is itself a literary genre with an impressive pedigree: “The funeral announcement for the novel is an old standby for the gloomy minded.” But he insists there’s something different about today.

In the only really extended chapter of the book, Epstein starts filling out the autopsy form himself, and the cause of death is a predictable kind of seamless garment: the internet and smartphones are ruining attention spans, political correctness is rampant in publishing, graphic novels are taking readers away from the more traditional sort, and a therapeutic culture overdosed on Freud means, ultimately, that no one has very much interesting to write about anyway.

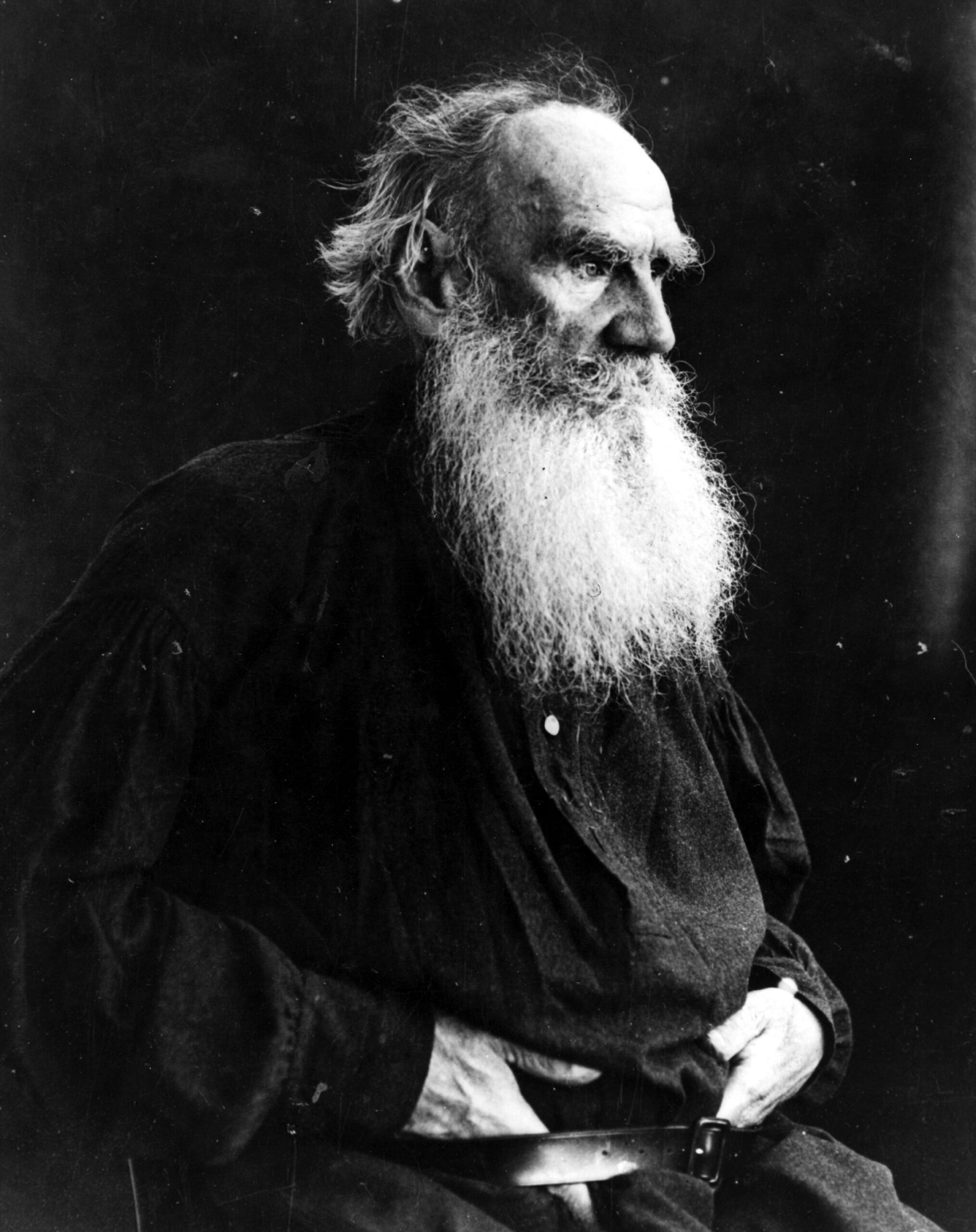

Throughout, Epstein leaves a distinct impression: He doesn’t really like novels; he likes Tolstoy, whom he calls “the greatest of novelists, perhaps the greatest writer of all time and among all genres.” He rattles off the big Victorian names often enough, has some praise for Proust, and justly champions Willa Cather—but have any other novels of note been produced? Say, since the Second World War? Pynchon is out. Barbara Pym and Iris Murdoch, forgettable. Updike, disappointing. Tom Wolfe, too journalistic. Mailer, Roth, and Updike wrote about sex too much—not a topic with much relevance to the real complexity of human life, presumably. Alice Munro is of “limited interest,” Toni Morrison is “more for teaching than reading,” Jonathan Franzen is too mean.

A list of recommendations is presented without comment and manages to include two living writers, and one novel from this century—Richard Russo’s Empire Falls. And when Epstein finally considers what he thinks of as a really “serious novel,” he comes up with the anticommunist canon: Orwell, Solzhenitsyn, Koestler, whose books were at least useful.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

Where has this left the contemporary novel? It’s hard to say. To assess the state of things, Epstein quotes with horror from reviews—he confesses that he limits his exposure to skimming the Times Literary Supplement. To illustrate the effect the internet might be having on literature, he attempts to quote (unattributed) from recent novels by Lauren Oyler and Patricia Lockwood, seemingly by pulling from Gemma Sieff’s double review for Harper’s, though he gets confused about which book he’s talking about.

The closest he gets to opening any of these recent novels is a long quote from the New Yorker’s latest Sally Rooney excerpt. He concludes, “I suppose this all comes under the rubric of The Way We Live Now. But why does it all seem so arid, so less than enticing?” Evidence of wokeness is outsourced to Becca Rothfeld in Liberties. Maggie Doherty in the Nation handles the heavy lifting, and reading, to illustrate how boring he finds campus novels. It is a remarkable coroner who can keep himself so far away from the body.

Answering the question of the title, The Novel: Who Needs It? presents a quick and convincing case. We all need the novel if we are to understand ourselves and our society; we all need good novels, great and true novels, if we are to live our lives without illusions about what sort of people we are. Epstein is right: “The knowledge provided by the best novels is knowledge that cannot be enumerated nor subjected to strict testing. Wider, less confined, deeper, its subject is human existence itself, in all its dense variousness and often humbling confusion.” With how distressing the way we live now can be, someone should find out if anyone is still writing them.