Can Trump Manage an Unbelievably Small War?

Few wars start with the intention of regime change.

When John Kerry was secretary of state under Barack Obama, he was widely mocked for saying a proposed military strike on Syria would be “unbelievably small.”

Few on either side of the 2013 Syria debate found those assurances believable. There was limited appetite at the time for even an unbelievably small war in the region, given recent experience with the bigger ones.

Can Israel fight such a war against Iran, with the U.S. role never growing beyond unbelievably small at the most? That is what President Donald Trump appears to be betting, based on the early promising results of the Israeli military strikes.

It’s certainly true that military interventions do not have to grow into full-blown occupations and nation-building projects. Trump’s first-term military campaign against ISIS was largely successful without metastasizing into Iraq War 2.0.

Afghanistan could have been conducted in a way more like the anti-ISIS blitz than the ill-fated 20-year war to transform that barren wasteland into something approximating a normal country that the Afghan conflict ultimately became.

From Grenada to the Persian Gulf War, Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush governed as if they learned some lessons from the Vietnam debacle even though they both supported that war at the time, and neither of them condemned it in retrospect (though there were at least arguably negative downstream effects from the first Iraq war that contributed to the second, far less successful one). The U.S. and its allies were also able to win the Cold War despite the failures in Vietnam.

If a more limited intervention is possible here, it will be because Trump is differently motivated than past interventionists. I was among those worried his strike against Iranian military officer Qasem Soleimani would lead to war. It did not at least in part because Trump quit while he was ahead rather than use Iran’s retaliation, which some described as “calibrated” at the time, as a pretext to keep going.

Trump had less success with his second-term strikes against the Houthis. But rather than let it turn into a forever war, he cut his losses, declared victory, and stopped the bombing.

I suspect Trump’s apparent reversal on the Israeli strikes—he has acknowledged publicly that he asked Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to stand down last month—began as a bargaining posture, an elaborate Trump-Netanyahu good cop–bad cop routine. But the strikes then appeared to weaken Iran enough that he began to think something more ambitious was possible, with Israel doing nearly all the work and taking the bulk of the risk.

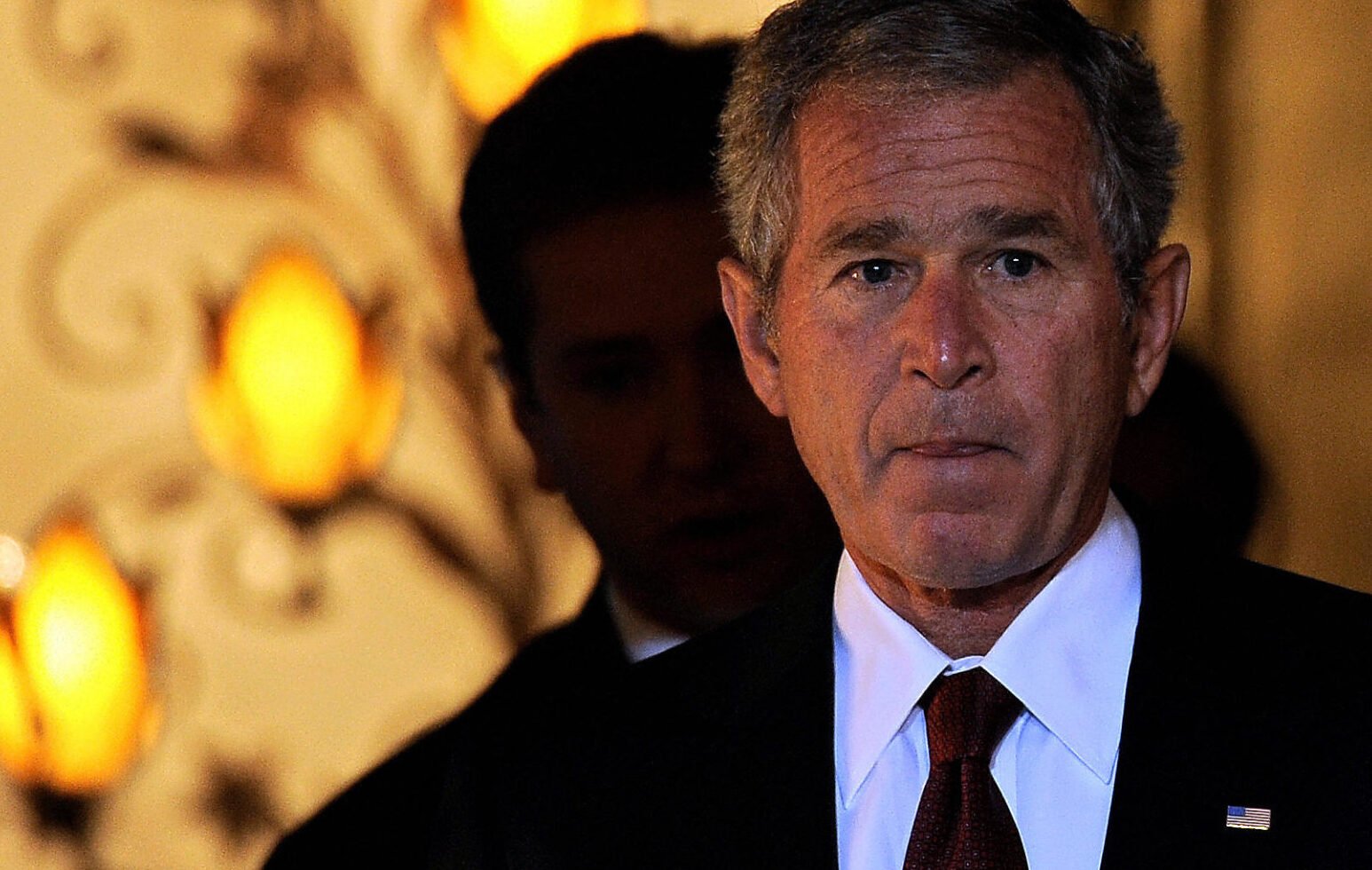

Trump may not be interested in a protracted war, but a protracted war is potentially interested in him. The lessons many conservatives have taken from the failure of recent past wars are that nation-building doesn’t work and democracy-promotion in most of the Middle East is simply idealistic mumbo-jumbo. The number of people who still believe in anything like George W. Bush’s second inaugural address is vanishingly small.

Those lessons are fine as far as they go. But relatively few people went into Afghanistan or Iraq wanting to nation-build. The talk at the time was of light footprints, cakewalks, and being greeted as liberators. After the shock and awe, the options are generally to do business with the remnants of a government that was deemed untrustworthy to begin with; leave behind a stateless vacuum to be filled by God knows what; or try to fashion a new, differently motivated government out of the postwar wreckage.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

And that’s where nation-building tends to come in. Overthrowing the Taliban wasn’t hard; creating a country that wouldn’t return the Taliban to power practically the moment the U.S. was a task left undone after 20 years of trying. Iraq was a largely predictable disaster, but not because Saddam Hussein’s army proved any more up to the challenge of fighting U.S. forces than during Desert Storm. There were exhilarating moments of toppling Saddam’s statue and pulling the filthy dictator himself out of his hidey hole. The problem was the aftermath.

The Iran debate has always fundamentally been about the regime. The case for military action has never been about the general enforcement of nuclear nonproliferation. It has been the character and nature of the Iranian regime: the argument that it cannot possess nuclear weapons because its government is run by religious fanatics against whom deterrence cannot work, and the much stronger argument that nuclear weapons would make it more difficult, especially for Israel, to inflict consequences on Tehran for sponsoring terrorism.

So I don’t dismiss the case that this could somehow be made to work, especially if Trump refuses to pay the bill at the Pottery Barn no matter who breaks what. But it is the regime-change part that could prove difficult to avoid and has the worst track record of working out. At a minimum, it is difficult to keep believably small.