Why the U.S. Will Never End Iranian Influence in Iraq

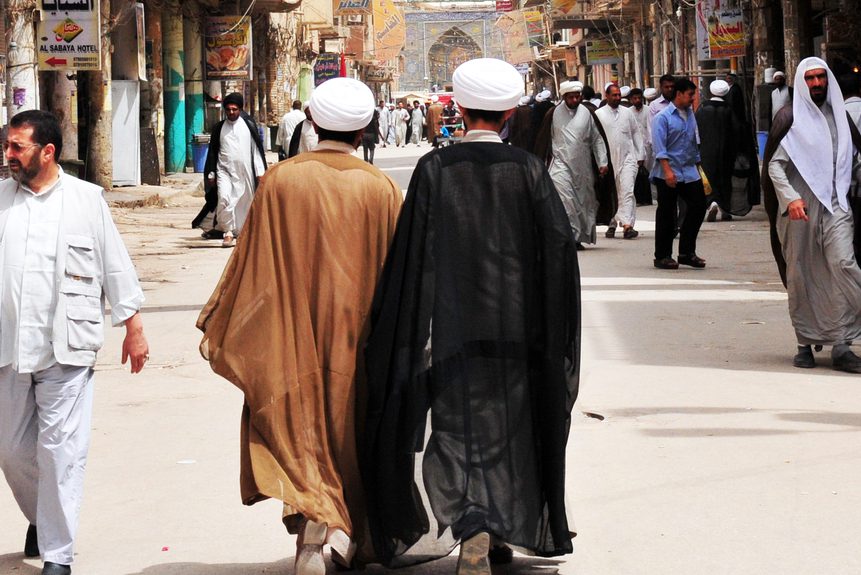

There is a power struggle in Baghdad. The country is torn between Arab influences from the west and a militant theocracy to the east. The religious leader of the neighbors in ancient Persia dispatches his top lieutenant to the city to engage in clandestine military action to bring the government under their thumb. This lieutenant is a hero in his country, known for his ruthlessness and efficiency but also his quiet and humble demeanor, harboring no ambition for riches or a higher position. His presence incenses and terrifies the Arab leaders and he is suddenly assassinated, adding another chapter to a long history of bloody violence in the region.

But this scene isn’t January 2020 outside Baghdad International Airport. It is 818 A.D., and the assassinated militant is Al-Fadl ibn Sahl, a Persian vizier serving the Caliph al-Ma’mun, who had recently named a Shia Muslim as his successor and was accused of being anti-Arab.

The assassinations of Al-Fadl and Iranian General Qasem Soleimani nearly 1,200 years apart aren’t completely identical—Soleimani was killed by drone strike from the United States, an Arab ally, while the Al-Fadl murder was rumored to be an inside job. But they illustrate the extensive and violent history of Persian and Iranian influence in the territory of modern Iraq.

This history is littered with outside empires trying to control the area and inevitably leaving, from the Mongols to the British, while the struggle between Sunni Arab and Shia Persian has endured. The United States may have the most powerful military the world has ever seen, but there is no indication we are able to change this pattern.

Much of this paradigm of internal struggle and failed external influence is due to geography. While empires attempt to exert control from hundreds or thousands of miles away, these cultures and religious sects have existed side by side and intermingled for millennia. The ancient Chinese proverb about the difficulty of governing distant lands—“The mountains are tall and the Emperor is far away”—is still relevant even in the era of modern technology.

Imagine if the Chinese government tried to limit the relationship between the United States and Canada. Even if the U.S. military was significantly less powerful and our country less populated, it would still be an enormous logistical and financial challenge to orchestrate from the other side of the world—and that’s before we would start to fight back.

The United States simply does not have the resources to prevent Iranian influence in Iraq. Counterinsurgency theory is still a relatively new and fluid science, but a general consensus is that a minimum of 20 counterinsurgent forces per 1,000 inhabitants are required to control an insurgency. For an Iraqi population of over 38 million, this would require 768,000 counterinsurgents, about 100,000 more than the active duty U.S. Army and Marine Corps combined. For Iran, it would require a force of 1.6 million, or the total active strength of the American, British and German militaries.

Fortunately, the U.S. does not need to counter Iranian influence in Baghdad to meet our national security requirements. Regarding the Middle East, our interests revolve around preventing terrorist attacks against our homeland and protecting vital lanes of commerce, especially those in the energy sector. Such interests are best preserved by improving our relationships with regional players and working to prevent conflict, not putting our weighty thumb on the scale for one side in an historic dispute.

Though Iran provides support for terrorist groups, their reach is limited to the region—removing U.S. forces from Iraq and Syria would greatly reduce the risk these groups pose to American lives. On the other hand, Sunni extremist organizations like Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State, which draw significant support from the Arab world, have posed significantly more danger to U.S. interests. The Iranians have, ironically, been on our side and on the side of the Iraqi government, in fighting them in recent years.

We must ask ourselves what we would get from reducing Iranian influence in Iraq, putting aside how difficult that would be. Iraq is not of strategic importance to the United States—it never has been. Whether you agree with the justification or not, a byproduct of removing Saddam Hussein from power was to disrupt balances of power and created opportunities for Iranian influence to expand. In the end, we are still there simply so we don’t have to admit our lofty ideological goals cannot be met.

Unfortunately, the obvious course of action—a policy of restraint and prudence that prioritizes our national security interests—remains ignored by Washington insiders who have built their careers on being Iran hawks. Until that changes, we will continue to waste lives and resources trying to push water uphill in an ancient Sunni-Shia conflict.

Robert Moore is a public policy advisor for Defense Priorities. He previously spent nearly a decade on Capitol Hill, most recently as the lead staffer for Senator Mike Lee on the Senate Armed Services Committee.

Comments