Why Statecraft is Still Soulcraft

America’s political square has taken ill. A recent survey found that 91 percent of Americans believe we are divided over politics; another showed that 58 percent have little or no confidence that their fellow citizens can have a civil conversation with those holding different views. This has infected the way we discuss public affairs: 85 percent of Americans say that over the last several years, political debates have become less respectful; 76 percent say they’ve become less fact-based.

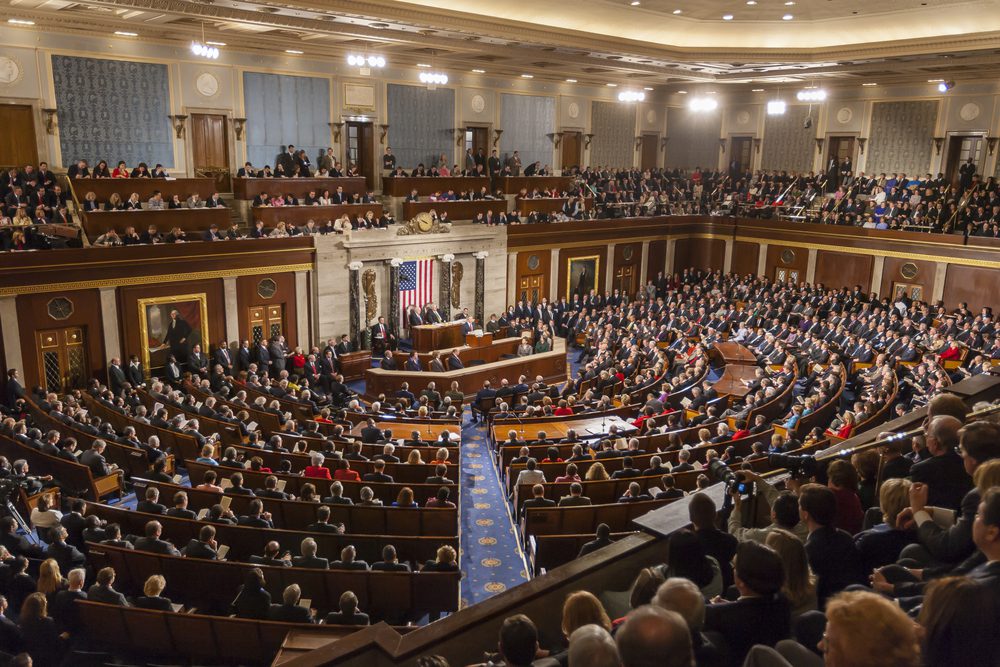

These sentiments are ultimately related to how we see our governing institutions. Only 17 percent of Americans believe Washington can be trusted to do the right thing all or most of the time. That’s down from three-quarters of Americans just a half century ago. Citizens’ concerns are aimed at both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue. Only 3 in 10 Americans say this president is honest and trustworthy. Congressional approval has been below 30 percent for a decade. Perhaps most worrying, 70 percent of Americans believe that our low trust in one another inhibits our ability to solve problems.

All of this endangers our ability to self-rule. Democracy, especially in a continental, pluralist nation where individual freedom is prized, requires that we demonstrate curiosity when participating in public debates, show accommodation to opponents, demonstrate restraint, and engage with integrity. In other words, a certain set of beliefs and behaviors are an essential component of governing the American republic. Indeed, in a 2016 paper for the Brookings Institution, scholars Richard V. Reeves and Dimitrios Halikias make the case—reasoning from arguments made 150 years earlier by philosopher John Stuart Mill—that sustaining the institutions of liberal democracies depends on the character of their citizens.

If one role of public education is to preserve our institutions and norms, then the development of character must be among its responsibilities. In other words, we must form young people committed to and capable of conserving our invaluable governing patrimony. However, during my nearly two decades of working on education policy at the state and federal level, in both the legislative and executive branches, I have been struck by how seldom the issues of character and virtue come up in discussions of statutes, regulations, and other forms of official government action. Such matters have certainly never emerged as a policy priority.

This is conspicuous because the K-12 policy debate is lively. During the past two decades, America has had heated discussions about accountability (e.g., standards, testing, performance reporting, teacher evaluation), equity (funding formulas, special education, re-segregation), choice (charters, vouchers, tax credits), and much more. But none of these conversations necessarily touches on the skills and beliefs related to participating fruitfully in our common affairs.

This is not to say that educators ignore character and virtue. In fact, teachers can model virtue and subtly form the character of students in a hundred different ways a day. As Stacey Edmonson, Robert Tatman, and John R. Slate argue in the insightful, comprehensive “Character Education: An Historical Overview,” educators in America and elsewhere have long considered moral and ethical development a key component of schooling, though political and social trends evolve and complicate what this actually means in practice.

But as we move from the classroom to the broader social, political, and policy conversations of schooling, it seems as though our willingness to engage explicitly in these issues evaporates. We feel comfortable talking about dates, facts, individuals, and theories of authority, but we are loath to talk about civic virtue.

♦♦♦

Civic virtue might be thought of as the sensibilities and actions of citizens that contribute to a good society. A similar definition describes it as the set of personal qualities associated with the effective functioning of the civil and political order. Embedded in this concept is the idea that individuals have not just personal rights but also obligations to the community. This means that a citizen must think and act beyond him or herself; it also means that this thinking and acting should be tethered to a collective understanding of the common good.

So there are at least two ethical dimensions to civic virtue: how we ought to act and what constitutes a healthy community. A similar concept is “character,” which has been concisely defined by Anne Snyder in The Fabric of Character as “a set of dispositions to be and do good.” In the context of public affairs, character can be thought of as the personal attributes that align a citizen’s thoughts and actions with civic virtue.

Over time, education scholars have attempted to clarify the meaning of character by describing its component parts. In his 2011 Phi Delta Kappan essay “Character as the Aim of Education,” David Light Shields offers four categories of character in a manner especially helpful to the discussion of schooling. First, referencing Ron Ritchhart’s work, Shields discusses “intellectual” character. This is knowledge, but it’s more than the mere accumulation of content. It extends to developing the personal dispositions that enable continued learning—traits like curiosity, open-mindedness, and skepticism.

A second is “performance” character—a set of habits “that enable an individual to accomplish intentions and goals.” This includes diligence, courage, initiative, and determination. Performance character is often described as “enabling excellence.” That is, young people, if they are to succeed in school and beyond, need to learn how to willingly engage in challenging work, stick with difficult tasks until successful completion, and bounce back after failure. In terms of productive engagement in public affairs in a diverse democracy, these skills will help budding citizens participate in sensitive but essential debates; work through complicated, arduous political processes; and continue to engage after losing a bruising policy battle.

The rub, however, is that intellectual and performance character can be worryingly agnostic regarding substance. Curiosity will help a student collect a great deal of information, but it won’t tell her what is good or bad. Likewise, an open mind can be filled with either wholesome or wicked ideas. One could courageously engage in either humane or inhumane reform, doggedly fight for either a just or unjust cause, and show great initiative for either charity or cruelty.

This is why a third category is necessary—what many have called “moral” character. Shields refers to it as “a disposition to seek the good and right.” Such a disposition can guide our application of curiosity, skepticism, confidence, and determination. Moral character can include an understanding of justice and enduring ethical rules, as well as honesty, integrity, humility, duty, gratitude, and respect. These values can help young people understand why equal opportunity is invaluable, why prudent language in debate is important, why discrimination based on protected classes is unlawful, why spreading false information is wrong, why societies develop policies to protect innocent life, why just-war theory shields non-combatants, and much more. When done right, the combination of intellectual, performance, and moral character can help young people mature and develop essential citizenship skills.

♦♦♦

But the education community can become squeamish when the term “moral character” is raised. A principal, school board member, or state legislator might worry that principles-based lessons about right and wrong inevitably invite religion into the classroom. They can worry that discussing natural rights could make some students and families uncomfortable. And as Reeves and Halikias argue, some liberals see state-sponsored instruction on character as paternalistic, impinging on individuals’ right to determine for themselves the nature of the good life and how to pursue it. In short, for those involved in public schooling, it can be far safer to focus on intellectual and performance character than moral character.

Understanding this fact can help us better appreciate a number of trends in public schooling. For instance, the recent infatuation with “grit” and “resilience”—often thought of as encompassing pluck, passion, and perseverance—seems an obvious manifestation of our preference for teaching performance character rather than moral character. Grit and resilience can tell us how to start moving, leap over obstacles, and pop back up when we fall, but they are muted about the destination.

The upshot for public life is troubling. To illustrate, take the many prominent political figures who behave in ethically objectionable ways but do so with great gumption and gusto. If we only teach young people about performance character, we have to concede that such public figures have demonstrated confidence, courage, initiative, and determination. But we are left without the vocabulary to critique their mendacity, carelessness, cruelty, vulgarity, and intemperance.

Likewise, in the place of specific language of moral character, we’ve substituted terms like “social justice” and “equity.” Though adjacent to morality, these concepts are ambiguous and subject to flexible interpretation. The meaning of “social justice” has been strenuously debated for decades and, to this day, its definition is still contested. Nobel laureate F.A. Hayek called the term a “mirage.” And though some today associate it with a progressive political agenda, it has roots in the teachings of Catholic social thought that elevate elements of individual duty and community solidarity. Similarly, “equity” is often in the eye of the beholder. It can be invoked by those advocating for either equal opportunity or equal results; a Rawlsian or Nozickian approach to redistribution; the rule of law or predetermined “fair” outcomes.

In the cases of both social justice and equity, we end up with pleasant-sounding terms that fail to provide future citizens with adequate direction on the content of admirable behavior. Thus, even if we produce gritty and resilient students, they may still lack an understanding of what they ought to apply their grit and resilience toward once they are in the public square.

♦♦♦

This challenge is brought to a fine point—and a potential solution is adumbrated—by Shields’s fourth and final category of character: “civic.” Here, he notes that a thriving nation requires the active participation of citizens; that active citizens must possess an appreciation of the common good; and that working toward the common good entails collaborative, civic work. He also contends that society should expect public schools to produce graduates capable of engaging in this process by cultivating civic character. According to Shields, elements of such character include “respect for freedom, equality, and rationality; an appreciation of diversity and due process; an ethic of participation and service; and the skills to build the social capital of trust and community.” To that list I would add an appreciation for the wisdom accumulated through tradition and custom, the recognition that local governing allows the flourishing of pluralism, and the understanding that democratic governing institutions and voluntary community associations are similarly valuable means of collective action.

Regardless of which elements a community determines should be part of its civic-character list, it is at least clear that such a list ought to exist. Intellectual and performance character do not answer the same questions as civic character; being curious and hardworking does not guarantee one will possess the habits and beliefs necessary for citizenship. Moreover, intellectual and performance character are an inadequate foundation for civic character. To successfully promote civic character we must lean on elements of moral character. That is, a commitment to liberty, democracy, pluralism, service, and positive law (traits of civic character) is built on citizens’ humility, honesty, gratitude, and respect (traits of moral character).

This suggests two broad lessons for the citizens aiming to influence public education. First, we must appreciate that performance character may be a necessary condition for a student’s development, but also that it is not sufficient. Performance character, no matter how inspiring its focus on grit and determination, does different work than other forms of character. The difference between performance character and moral, civic, and intellectual character should be the starting point for reform efforts.

Unfortunately, it is not always so. In a 2012 chapter for the American Psychological Association, Marvin W. Berkowitz, a professor of education at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, offers a framework for how schools can influence students’ moral psychology. He describes an “anatomy” that includes multiple moral domains as well as “foundational characteristics,” like perseverance and courage. Though he does not use the exact same moral/performance language as Shields, he does clearly identify the difference between morality and the personal characteristics that enable one to act morally. The problem he notes is that “schools rarely consider this distinction as they generate lists of values or virtues to guide their character education initiatives.”

Fortunately, some have recognized this distinction. For instance, in a short 2003 paper, the Character Education Partnership offers “Eleven Principles of Effective Character Education.” The very first principle argues that ethical values form the basis of good character. The second principle describes the thinking, feeling, and acting elements of character. The key takeaway here is that morality is the core of character education; subsequent to that is instruction on our cognitive, emotional, and behavioral engagement. Similarly, “Character Counts,” a widely used framework, observes six pillars—trustworthiness, respect, responsibility, fairness, caring, and citizenship—that recognize the role of moral and civic character.

♦♦♦

The second lesson is that our policymakers—citizens’ representatives—need to engage this issue more fully. Unfortunately, leaders have come up with numerous ways to avoid advocating moral and civic character. Teaching students the value of “grit,” “social justice,” and “equity” appear to be common off-ramps. But traditional debates over history content standards often have one side emphasizing dates and names and another emphasizing theories of power and identity—while both sides ignore the role of character and virtue. Similarly, debates over civics often hinge on whether content knowledge or activism is prioritized—with character and virtue both largely ignored.

Another inadequate substitute is “social-emotional learning,” which has recently become a popular way to talk about the wide array of schools’ non-academic responsibilities. One definition of SEL is “the process through which children and adults understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions.” SEL can be pursued with character in mind; for example, The Aspen Institute’s major 2019 SEL report, “From a Nation at Risk to a Nation at Hope” considers “character and values” one of three categories of skills and attitudes that describe how learning occurs. But other SEL frameworks leave out character, ethics, and morality entirely, instead focusing on attributes associated with intellectual and performance character.

State leaders should consider how best to formally integrate character education—especially moral and civic character—into policy issues. Civics is a natural place to begin. A 2016 study found that while most states have some kind of assessment for civics, only 15 make demonstrated proficiency on such tests a condition of high school graduation, and only 17 include civics and social studies in their accountability systems. And of course, the extent to which moral or civic character is reflected in these assessments varies.

But there might be movement in the right direction. An important 2003 report titled “The Civic Mission of Schools,” produced by the Carnegie Corporation of New York and the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement, argued that competent and responsible citizens have four categories of attributes, one of which is the possession of “moral and civic virtues.” A follow-up report from 2013, “Guardian of Democracy: The Civic Mission of Schools,” concurred, noting that self-government “requires citizens who are informed and thoughtful, participate in their communities, are involved in the political process, and possess moral and civic virtues.”

Perhaps influenced by such work, in 2013, a coalition of groups engaged in social studies education released the “College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework for Social Studies State Standards,” a document designed to inform the upgrading of state content standards and the development of instructional materials. In several places, it highlights the importance of civic virtues (including honesty, mutual respect, cooperation, equality, freedom, liberty, attentiveness to multiple perspectives, and respect for individual rights). It notes that such virtues apply to both the interactions among citizens and the activities of governing institutions. A 2018 study by the Brookings Institution found that, by September 2017, 23 states had used or were planning to use the C3 framework. Similarly, the civics framework for the 2018 administration of the National Assessment of Educational Progress includes considerations of “public and private character” under the “civic dispositions” component. Private character includes traits such as “moral responsibility, self-discipline, and respect for individual worth and human dignity.” These are deemed “essential to the well-being of the American nation, society, and constitutional democracy.”

There are also ways apart from standards and assessments that policymakers can advance education related to moral and civic character. The Jubilee Center for Character and Virtues at the University of Birmingham has produced a guide called “The Framework for Character Education in Schools.” Though aimed at practitioners, it can be read to imply a set of policy recommendations. For example, teacher education standards and educator certification and licensing regulations reflect what we believe teachers ought to know and be able to do; strong families support the development of character; student nutrition and health are prerequisites for the acquisition of character; direct instruction and strong curricula related to ethics can enable students to learn character; courses enabling students to grapple with moral challenges facilitate character development; and character can be taught through role modeling and mentorship. The point is that as they contemplate rules related to teacher training, course development, discipline, graduation requirements, and much more, our education policy leaders have ample opportunity to prioritize character.

Jubilee’s framework also articulates why those in positions of governing authority—irrespective of political or ideological leanings—ought to engage in these matters. “The ultimate aim of character education is not only to make individuals better persons but to create the social and institutional conditions within which all human beings can flourish.” That is, those who believe that statecraft is soulcraft will recognize the valuable role public institutions can and should play in developing the character of students. But even those who have a more modest vision for the state should appreciate that our governing and civil-society institutions need to be led and populated by individuals of character so that those institutions can foster a social environment such that free citizens can thrive.

Andy Smarick is the director of Civil Society, Education and Work at the R Street Institute. He is a former president of the Maryland State Board of Education, New Jersey deputy commissioner of education, and aide in the White House Domestic Policy Council.

Comments