When Irish Eyes Are Closed to History

Imagine if the birth of the United States of America had emerged only after a controversial peace treaty was signed to end the American Revolution, leading to utter division among the states and civil war immediately erupting in the aftermath. Imagine as well beloved national heroes in our history squaring off on opposing sides—Northerners such as Benjamin Franklin and John Adams facing off against Southerners like George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison.

Now add to that yet another tragedy: the ensuing civil war, which witnesses the victory of the pro-treaty forces, leaves several states under the auspices of British rule, so that the nation’s wounds are not healed but rather inflamed. The treaty leads not to a lasting peace, but rather to almost another century of intermittent, low-grade civil war pitting pro-treaty compromisers and anti-treaty nationalists against each other.

If you can begin to imagine all that, then thank our lucky 13 (or 50) stars that we have been spared the fate of Ireland, the all-too-easily romanticized Emerald Isle. Now you have some dim notion of the trauma of Ireland’s birth. And that’s just for starters—the full history of the agonies stretch back to the 12th century and beyond.

♦♦♦

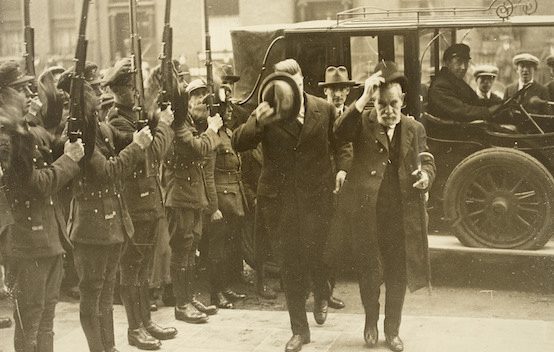

All this is worth remembering because Ireland recently observed an important anniversary—the centennial of the Irish War of Independence. It went virtually unreported in the American media, yet it has relevance to the state of our own union—and cautionary lessons for Americans, too. A century ago, on January 21, 1919, the War of Independence in Ireland broke out, the Irish equivalent of the American Revolution. It led to a bloody civil war that exploded 18 months later when the republicans (the Irish Republican Army), who insisted on an independent and fully unified Irish republic, refused to accept the Anglo-Irish Treaty emerging from negotiations with the British because it would split the nation, leaving six northern counties still part of Britain.

The year-long civil war proved, if anything, even more divisive and embittering than the revolutionary war. (Irish nationalist forces triumphed, but only because of massive support militarily from the British.) So the Irish Civil War, which officially led to the establishment of the Irish Free State, ended only in an official sense. Practically speaking, Ireland was plunged into guerrilla warfare and terrorism until nearly the end of the 20th century. No lasting, final peace was achieved until the Easter agreement of 1998.

Almost every Irishman knows all this. Hundreds of thousands of Irish citizens have grandfathers who fought in the War of Independence, and tens of thousands more, especially in the northern province of Ulster, have family members who were injured or killed in internecine warfare between the IRA and the British army and its Irish Protestant supporters.

♦♦♦

Perhaps no country has been so haunted by history as Ireland. You will not go far before stumbling across a heated debate, abetted by a few mugs of Guinness, not only about the War of Independence and Civil War, but even the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, where Protestant King William of Orange versus defeated Catholic King James II. You might even hear an exchange about the Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169, which marked the beginning of more than 800 years of British occupation—or, er, involvement—in Ireland.

Is all that ever going to change? Beginning this school year, as Minister of Education Ruairi Quinn told the nation last May, all 26 counties in the Republic of Ireland have instituted a new set of requirements for the Junior Certificate, the national leave-taking examination for 16-year-olds (equivalent to requirements for U.S. middle school students before they matriculate to high school). The most important, and controversial, curricular change was the decision to drop Irish history as a required course, changing it to one option among other subjects.

Now an Irish wit might say, and probably already has said in plenty of pubs, that this is a good thing—historical amnesia will soon set in and nobody will remember 1922 or 1916. And so the nation’s long-standing and still-simmering antagonisms between Catholics and Protestants, and Irish and Scots-English, will gradually dissolve of their own accord.

A nifty solution, eh?

Well, not exactly. Another historical fact is that Northern Ireland, which is where so many tragic and traumatic events in the recent past have occurred, abolished history as a school subject several years ago, along with the rest of the United Kingdom. (The six chiefly Protestant counties of Ulster, which make up the region officially known as Northern Ireland, are part of the UK and subject to its laws.) And just as prevails across the sea in Britain, fewer than 40 percent of Northern Irish students currently elect to study history.

The lesson would seem to be the famous warning of George Santayana: “Those who fail to remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Fortunately, a substantial (if shrinking) number of Irish do not agree with the curricular change—and seek to remember (and learn from) the checkered Irish past. Many prominent political and cultural figures in Ireland agree. For instance, the Lord Mayor of Cork, Mick Finn, fears that the change amounts to nothing less than “turning our back on history—local, national, and global.” He argues that the dire scenarios that we have already discussed—the wounds of history being so open and still festering—will only worsen as the years pass.

Mayor Finn is not alone. The newly re-elected president of the Republic of Ireland, Michael Higgins—a history professor before becoming a national statesman—has expressed “deep and profound concern” about the already noticeable decline of historical knowledge among Irish youth, which will only worsen without the history requirement. Discussing the curricular change on the occasion of the publication of the grand new scholarly edition of The Cambridge History of Ireland, he reminded his fellow Irishmen: “A knowledge and understanding of history is intrinsic to our shared citizenship, to be without such knowledge is to be permanently burdened with a lack of perspective, empathy, and wisdom.”

Will a national amnesia overtake Ireland in a generation or two? It is possible. Irish youth, one critic predicts, will soon regard Skellig Michael as nothing more than the set for the Star Wars films—as if Americans were to view the Empire State building as just a location in the King Kong movies (or native Philadelphians take the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art as merely the site of Rocky Balboa’s training regimen).

But perhaps the situation is not so hopeless. The Irish Ministry of Education announced in mid-November that it would “review” its decision for the upcoming year. That is welcome news.

Haunted history cannot be healed by pretending that it is a mere featherweight. Facing the past means facing it down—and that is done only through knowledge and awareness. Otherwise a free people becomes enslaved just as surely as the sheep-like citizenry of Orwell’s 1984, who bleat in unison: “IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH!”

John Rodden has written on Irish history in The Review of Politics, The Midwest Quarterly, and other publications. John Rossi is professor emeritus of history at La Salle University.

Comments