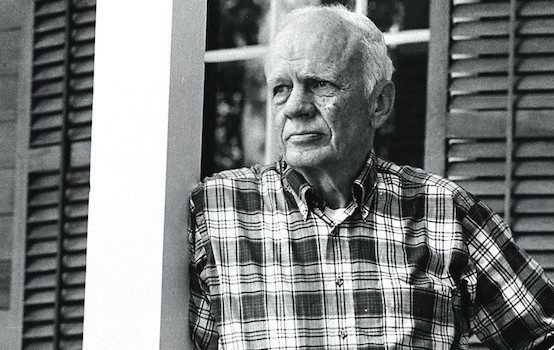

Walker Percy Ponders the Joy and Risk of Naming the World

Symbol and Existence: A Study in Meaning, Walker Percy, Mercer, 2019. 271 pages.

Three years before he died, Walker Percy remarked that one of the pleasures of “reading” a bibliography of his work was “recollecting the semiotic sections of The Message in the Bottle and Lost in the Cosmos—chapters generally disliked by most readers.” Why did he enjoy remembering these? Because, he writes, they showed “that most of the current theorists of language—structuralists, transformationalists, behaviorists, etc.—are up shit creek and can’t get out without crawling over eight-year-old Helen Keller in North Alabama.”

Percy aficionados will know what he is getting at, but if it’s been awhile since you’ve read Percy, here’s a primer: He argues in these pieces that while linguists have explained all sorts of things about language—how signs work in a system and how words are acquired to produce certain events—they have failed to explain the most important thing about it: meaning. When you say the word “water,” for example, you are not merely using arbitrary sounds to cause a glass of the stuff be placed on a table for you to drink. You are also referring to the thing itself, and we have forgotten, Percy argues, how astonishing this is. Helen Keller, in her autobiography, which Percy quotes, recalls how she learned the word “water” one day when her teacher placed her hand under a spout:

As the cool stream gushed over one hand, she spelled into the other the word water, first slowly then rapidly. I stood still, my whole attention fixed upon the motion of her fingers. Suddenly I felt a misty consciousness as of something forgotten—a thrill of returning thought, and somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that “w-a-t-e-r” meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. That living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, joy set it free!

What “happened inside Helen’s head?” Percy asks. It’s hard to say, but the larger problem, Percy argues, is that theorists of language aren’t even asking the question.

As far as I can tell, they still aren’t, and if Percy enjoyed recalling how these pieces exposed the weaknesses of modern theories of language, he’d be thrilled with the publication of his book Symbol and Existence: A Study in Meaning for the first time in its entirety, from which those pieces were taken. Percy wrote Symbol and Existence while he was writing his first novel, The Moviegoer, but he was unable to find a publisher. He returned to the book throughout his life and eventually donated two drafts of it to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1983. The Percy Estate donated two more after Percy’s death—in 1994 and 2007—and there they sat until now. Over half of the work has never been published.

All of Percy’s novels are about the relationship between language and the self in one way or another, and Symbol and Existence, as it turns out, is Percy’s most complete account of this relationship, laid out in his typically no-nonsense, occasionally breezy, sly prose. As Percy argues elsewhere but most clearly in Symbol and Existence, the act of naming things, as amazing as it is and as much freedom as it seems to offer at first, also shows us that the one thing we can’t name is ourselves. The scientific method is a powerful tool for naming things, but the one thing it can’t name is the scientist. It may be able to describe how the scientist’s body works and how his body is similar to or dissimilar from other bodies, but it can’t name that discrete thing called self. What’s worse is that the better we become at naming things, the more evident our namelessness becomes, and so modern man, already a ghost in a machine, becomes ever more insubstantial as he names with greater precision the mechanics of his existence.

The other strange thing about language is that while it gives things an initial identity, it also obscures that identity over time. When Helen Keller learned the word for “water” in the example above she became aware of a distinctness the stuff hadn’t possessed for her until that moment (not that it was without any distinctness before). The problem is that the repeated use of the word swallows the thingness of water so that it is nearly lost. Language, Percy writes, “operates not only as a means of knowing but also as a means of concealment.” Objects can become “encrusted by a symbolic simulacrum”—a simulacrum that can only be broken (temporarily) by accident or art.

Percy’s early novels are peopled with wanderers who try to do just that. In The Moviegoer, for example, Binx Bolling is “adrift,” struck by a feeling of “malaise”—a sense that he is out of place in the world and the world is increasingly lost to him. So he seeks out “rotations.” These are experiences of the world (or what Binx calls “the new”) “beyond the expectation of the experience of the new”: “For example, taking one’s first trip to Taxco would not be a rotation, or no more than a very ordinary rotation; but getting lost on the way and discovering a hidden valley would be.” This is because it would lead to an experience of the “hidden valley” that would be new in a way it wouldn’t otherwise be because of its sudden discovery, wholly unexpected, temporarily breaking through the everydayness of life.

In The Last Gentleman, Will Barrett, a Southerner living in New York, uses a telescope briefly to separate people and birds from their everyday contexts and so see them momentarily anew. The problem is that while the telescope “recovers” these objects by making every “grain and crack and excrescence” visible, these details eventually produce a kind of paranoia: “Every day the sky grew more paltry and every day the ravening particles grew bolder…. Sitting in the park one day, he heard a high-pitched keening sound directly over his head. He look up through his eyebrows but the white sky was empty.”

But in later novels, Percy presents us with another solution—at once more successful and horrifying: become part of the machine by numbing one’s sense of self through technology (Love in the Ruins) or drugs (Thanatos Syndrome). In short, give into death; and one wonders if this isn’t exactly what is happening across America, as news of families and towns ravished by opioids grabs headlines. Percy rightly saw that when faced with a deepening sense of loneliness and despair, death can seem like a gift.

One thing that may surprise even Percy scholars is the degree to which Percy hopes in Symbol and Existence that a “radical science of man”—one that is committed to describing phenomena like naming and knowing “dynamically” without reducing them to brain synapses—might save modern man from his predicament. It would be a science, even, that would describe the joy of naming, “a joy, which, unlike all previous pleasure, is unrelated to the economy of biological needs and satisfactions.” This is why, Percy writes, he is not calling for less scientific rigor when it comes to making sense of language, but more.

Novels, however, have a rigor of their own, and while Symbol and Existence is clearly the product of an original mind, what better medium than the novel to capture the predicament of modern man, the magic of thought, and the joy and risk of naming the world?

Micah Mattix is the literary editor of The American Conservative.

Comments