The Senate Against Democracy

George F. Will is worried about democracy. Not that it’s going under, as the Jan. 6/Ukraine/Elon-panicked cat-ladies breathlessly warn us in most opinion pages. The longtime Washington Post columnist is simply concerned that it’s starting to go in directions he won’t like.

Citing Jonathan Haidt, a favorite intellectual of high schoolers and wine moms from Manhattan to Sacramento, Will observes that social media has made much of life performative over the course of the last decade, “elicit[ing] ‘our most moralistic and least reflective selves,’ fueling the ‘twitchy and explosive spread of anger.'” This is true of the United States Senate, which has fallen victim to this general trend as members of the upper chamber dabble online in “the little arts of popularity” (Hamilton’s unapproving phrase).

I hope Will doesn’t really buy his own explanation. To suggest the devolution of the Senate is a mere decade-old development attributable to the rise of sites like Facebook is more ahistorical, not to mention politically naive, than can possibly be expected from a man of his learning.

Midway through his column, it becomes apparent that George Will’s anti-senatorial turn is not entirely one of principle. He fears one thing in particular: President Josh Hawley. His proposed solution to the concerning prospect of the Missouri populist’s ascendance to the White House is a constitutional amendment banning all current and former senators from seeking the presidency.

Will is no doubt aware of the 17th Amendment. He has long been a public critic of it. And yet, it seems, he fails to realize that the problems that so vex him now can all be traced back to that disastrous development.

In 1913, overcome by the liberalism that had swept the country (and much of the West) in the preceding half-century, the states ratified an amendment completely transforming the nature of the Senate. Whereas the Founders’ design provided for the selection of two senators by each state legislature, the amendment mandated direct election by a majority of the given state’s voting population.

The select upper chamber, previously insulated from the vulnerabilities of large-scale popular voting and linking each state as such to the federal legislature, became effectively redundant. The power of the states was greatly weakened, and the Senate itself was effectively changed from an American aristocracy, modeled as it was directly on the Roman Senate, to a House of Representatives without proportionality.

Yet the fault Will supposedly finds in Sen. Hawley—a flair for the theatrical, a tendency to grandstand—is a function of the pressures of direct election. Were Hawley’s position assigned as the Constitution laid out in the beginning, he would be free to do exactly as a senator is supposed to do. But history is not so kind: He has elections to win, and so do 99 others.

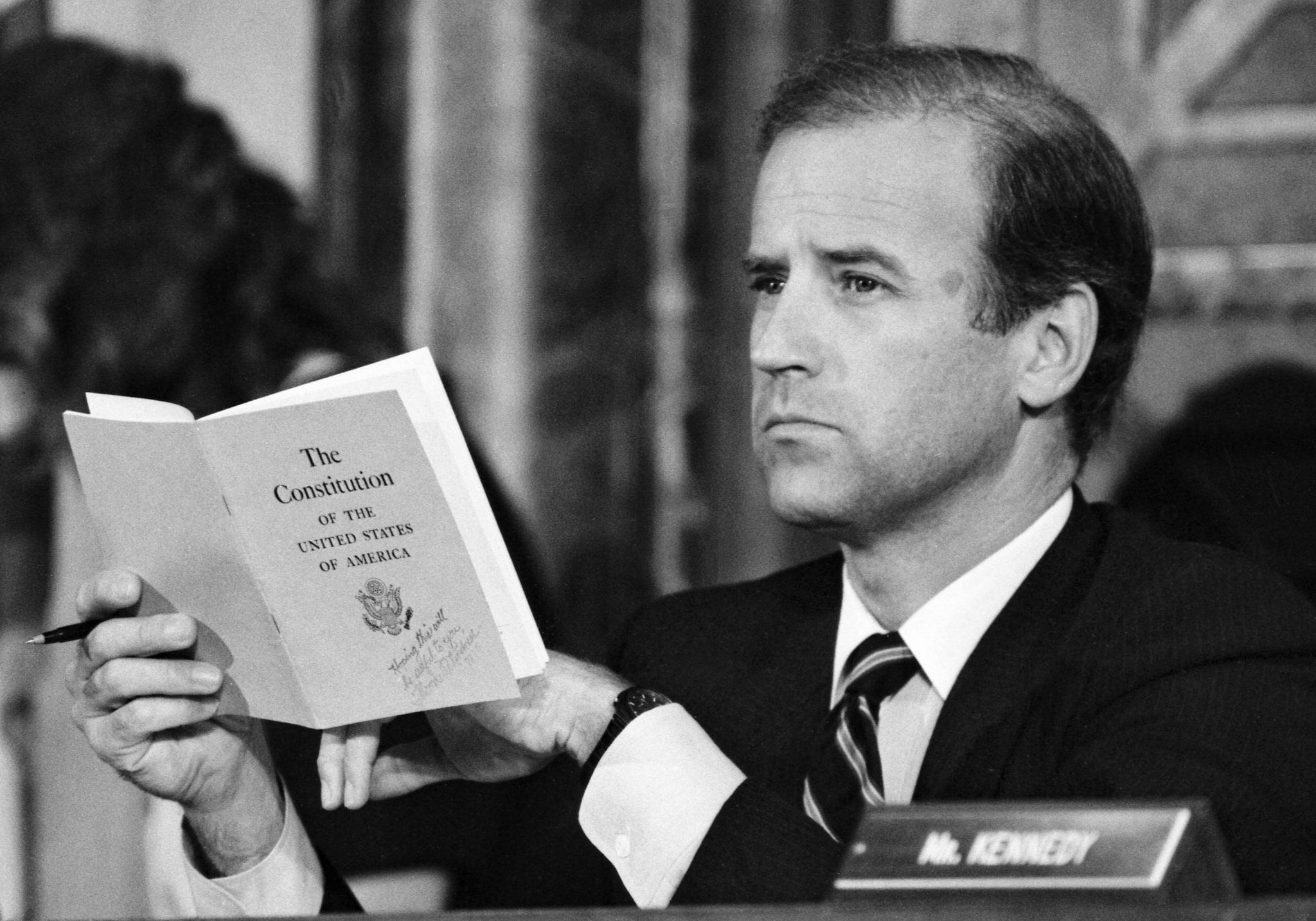

It is true that the Senate as it exists produces rather unfit candidates for the office of president: legislative tinkerers and two-bit rhetoricians who are hardly aware of, much less prepared to bear, the gravity of the executive’s role. People like Joe Biden, Barack Obama, Kamala Harris, and Ted Cruz. But the Senate as it ought to be—a defense against the dangers of mob rule, a governing body tied to the states and elevated above the concerns of petty politics—would be a fine selection pool for the chief magistracy of the Union.

Federalist no. 68, on the mode of the president’s election, seems to have inspired Will’s ludicrous proposal. The Hamilton-authored essay, like the Senate and Publius’s defense of it, is one of the more anti-democratic aspects of the Founding. It presents the Electoral College, again, as it was designed and not as it has become: as an actually deliberative body. Though it, too, has been rendered redundant, the Electoral College was meant to serve a purpose. Under the design of the Constitution, it actually chose the president.

The democratizing process that has ravaged the Senate has done the same to the presidency. But it doesn’t have to be this way. The Founders were well aware of the “low intrigue” inherent to democratic politics, “the little arts of popularity” practiced by those who must secure majority support among the masses. In a mixed regime they set up shields against them, including those in the Senate and the presidency—a uniquely American aristocracy and monarchy, respectively.

Conservatives ought to embrace those protections, not undermine them further. And if we are still worried about the corrosive forces of democracy and progress, the prospect of demagogy overtaking the weakened bulwarks of the American order (and we should be), then Alexander Hamilton himself has proposed some further safeguards. He that hath ears to hear…

Editor’s note: This article has been emended to correct Jonathan Haidt’s surname.

Comments