The Roots of Segregation

Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America doesn’t start off in the Deep South, Detroit, Baltimore, or the multitude of other places in the United States where segregation has often been examined. Instead, the research associate at the Economic Policy Institute begins his exploration in an unlikely place: San Francisco. There readers find Frank Stevenson, a transplant from Louisiana who found work in the booming manufacturing sector during World War II.

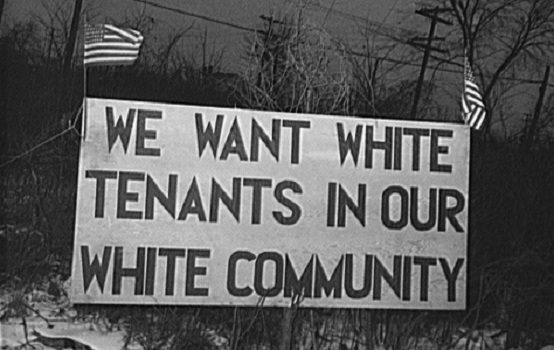

Stevenson’s story is typical of the African-American experience. He works hard but is blocked from access to new homes and certain jobs because of the color of his skin. Rothstein meticulously describes how local (via zoning and housing associations in places like Palo Alto) and federal (though discrimination in guaranteed mortgages from the Federal Housing Administration) authorities worked hand-in-hand to create segregated neighborhoods as black migrants came to California for the same reason so many others did—to find a slice of the American Dream. His conclusion that governments could impose segregation “where it hadn’t previously taken root” serves as a salient message that carries throughout the book.

The purpose of The Color of Law, Rothstein writes, is to “contemplate what we have collectively done and, on behalf of our government, accept responsibility.” Well-documented, and versed in academic histories from scholars such as Thomas Sugrue and Kevin Kruse, this book states something obvious but rarely discussed. Following in the vein of Ta-Nehisi Coates’s “The Case for Reparations,” it adds to the proof that, despite having deep roots in this country, many generations of black Americans have been placed in economic situations more akin to those of newly arrived immigrants than to those of the Sons or Daughters of the American Revolution. It serves as a reminder that African-Americans have—at a maximum—fully participated in American capitalism for just a few decades.

Rothstein’s work should make everyone, all across the political spectrum, reconsider what it is we allow those in power to do in the name of “social harmony” and “progress” with more skepticism.

For oppression to exist there must be a culture that accepts it—or at least tolerates it—and a government capable of enforcing it. The book offers modern examples of how federal and local agencies, often established under the banner of promoting affluence, became tools of racial discrimination based on the longstanding belief that black and white Americans hold “natural” antipathy toward each other. For centuries this belief—spurred on by a mix of fear and nonsense—has shielded politicians and lawmakers as they reinforced stereotypes to consolidate authority. The Color of Law shows how this operated across the country during the first half of the 20th century and in many places lingers today. No equality is found in these pages, only power and control.

Rothstein wrote The Color of Law for an audience of five: Chief Justice John Roberts and his conservative colleagues on the Supreme Court. He “adopt[s] the narrow legal theory of Chief Justice Roberts, his colleagues, and his predecessors. They agree that there is a constitutional obligation to remedy the effects of government-sponsored segregation, though not of private discrimination.” Rothstein argues that, in fact, most segregation falls “into the category of open and explicit government-sponsored segregation.”

While likely not his intention, the result is a successful showing of why progressive government, replicated by New Deal acolytes at the local level, often empowered politicians, federal agencies, and local planners to implement their racial biases against African-Americans. The Color of Law is a story about how, when allowed, authorities will pick economic winners and losers to their own benefit rather than the benefit of the country as a whole, especially if it helps them win votes.

The Color of Law does a magnificent job explaining how much the American Dream, although commonly imagined as building the next Apple or Facebook in a garage, has relied on the multigenerational growth of wealth—homesteaders owning and developing land to pass on to the next generation, immigrants working in factories to allow their children to go to college. But from racialized public housing and zoning, the enforcement of discriminatory housing covenants, and the overt denial of government-backed financing for black Americans, to sanctioning private mobs to drive African-Americans out of middle-class neighborhoods, government intervention kept many from partaking in this generational prosperity. While white families accrued wealth as housing prices grew from the 1950s onward, many black Americans fell further behind. Rothstein magnifies how the “cycle of poverty,” “disintegration of the family,” and other bywords used to describe black impoverishment can be directly attributed to government decisions—or government failure to enforce basic rights, in the case of violence against new black arrivals in white neighborhoods.

Rothstein’s remedy for these problems, however, relies too much on a tedious reading of the 13th Amendment. (“Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”) Rothstein argues that the amendment requires the government not only to prohibit slavery, but also to remove its legacy from the nation. It’s an argument for words that aren’t there.

Though he doesn’t let Progressives off the hook entirely, Rothstein also contends that the compact between Progressives and Southern segregationists to block black access to programs like the FHA resulted from “the stain of slavery” rather than Woodrow Wilson’s racism or the political cynicism of New Dealers. He too often argues that the best way to solve problems caused by giving lawmakers arbitrary authority over the lives of millions in the past is to increase arbitrary authority today. This is like saying the best way to prevent the next house fire is to give different arsonists the matches. Programs to rectify the past misdeeds of government should be market-oriented and focus on empowering individuals rather than perpetuating more and more top-down management of our society.

The Color of Law is on more solid ground when it focuses on the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equality under the law, and conservatives would be wise to heed Rothstein’s words when he notes that the “Bill of Rights and the Civil War Amendments are designed to restrict popular majorities” from using the government to enforce discrimination. Newly seated Justice Neil Gorsuch illuminated this path during his confirmation hearings. Gorsuch called the 14th Amendment “maybe the most radical guarantee in all of the Constitution and maybe in all of human history.”

This is how conservatives can promote the idea that a limited government of separated powers helps everybody. The new justice has offered a guiding light pointing the way toward taking on the enduring legacy of black enslavement. Urban conservatism, based on the ideals of individual empowerment through personal liberty and equal opportunity, must be part of the conversation if we are to have a healthy democracy. The Color of Law explains why.

Rothstein proves that neither “natural progression” nor the free market has driven modern segregation in the United States. It was planned. Most often, the forces of government have played a major role in shaping where we live, how we finance homes, and where our children attend school—often to the detriment of African-Americans. Rothstein is right in arguing that this is something Americans should reckon with.

The Color of Law should be a clarion call for supporters of the Constitution, limited government, and the free market to think about urban areas, poverty, and race relations in new ways. Conservatives should read this book and add it to their repertoire when they offer an alternative, positive vision to progressivism’s status quo of ever-growing government and interference into the market. The Color of Law shows what happens when Americans lose their natural rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, or in the case of African-Americans, when there are those still waiting to receive them in full.

Carl Paulus is a historian of American politics and author of The Slaveholding Crisis: Fear of Insurrection and the Coming of the Civil War.

Comments