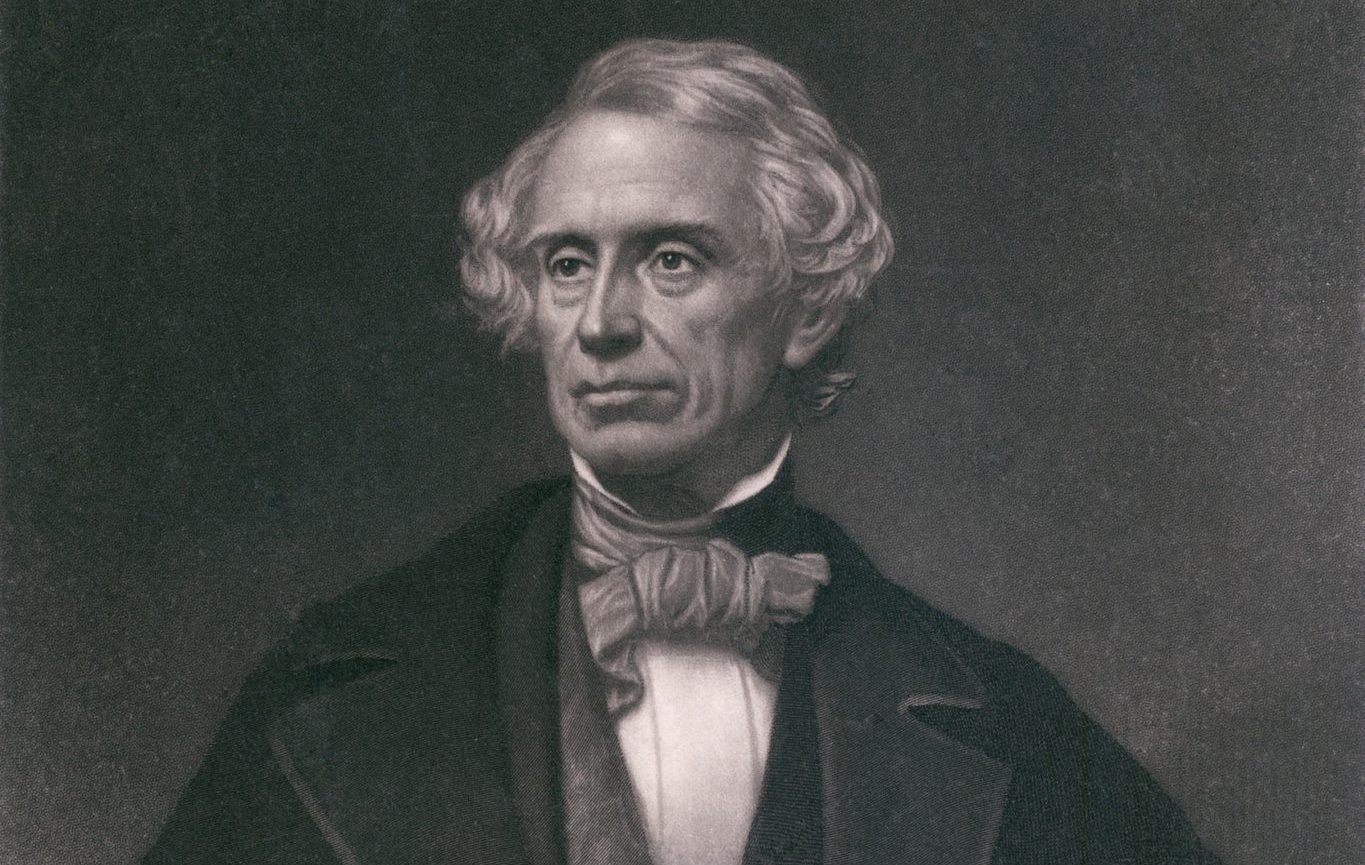

The Realism of Samuel Morse

In 1835, Samuel F.B. Morse published a sensational work warning his fellow Americans that the sovereigns of Europe necessarily viewed the United States as an existential threat. Foreign Conspiracy Against the Liberties of the United States went through seven editions between 1835 and 1855. Morse, a devout and theologically conservative Congregationalist from Massachusetts, argued that the United States’ national commitment to liberty made it a unique expression of political theories that by its nature was deemed a threat to autocrats. He believed that the Austrian and Russian emperors particularly feared the American republic and that they planned to undermine the United States at every available opportunity.

Autocrats, not Americans, were the aggressors in the war between autocracy and democracy. Morse loathed autocracy but, unlike later generations of American policymakers and intellectuals, Morse rejected the idea of liberal imperium or wars in the name of democratic freedoms. Morse catalogued what he believed were the evils of autocracy because he believed Americans needed to be aware of their unique national strengths. Liberty, he believed, was fragile, and needed to be defended.

Pleas for Americans to heed liberal revolutions in Europe have had many meanings through the years. In the latter part of the 20th century and the early part of the 21st century, policymakers, particularly neoconservatives, believed that the entire world might be remade in the image of American liberal democracy. Although earlier generations of Americans hoped for democracy and self-determination to flourish, they like Morse had grave reservations concerning the United States’ ability to bring about en masse liberalism in Europe and even graver reservations concerning the ability of European peoples to thrive.

Liberal liberties could not be exported everywhere, largely because the United States liberal-conservative tradition was built on generations of Anglo-American political practice and presuppositions. “Who among us,” Morse asked, was not aware that a “mighty struggle of opinion is in our days agitating all the nations of Europe; that there is a war going on between despotism on one side, and liberty on the other.” Americans who cared about liberty should have had “deep anxiety” as they watched “the vicissitudes of the conflict!”

The United States cared about democracy and liberal freedoms because the American Union “demonstrated, by successful experiment before the world, the safety, the happiness, the superior excellence of a republican government, a government proceeding from the people as the true source of power.” The American republic enjoyed “the rich blessings of such a government.” The success of the American experiment in self-government meant that Americans observed with more than mere passing interest efforts of “nations to break away from the prejudices and habits, and sophistical opinions of ages of darkness” in their struggle to “attain the same glorious privileges of rational freedom.”

Societal commitment to liberal freedoms did not, however, mean that Americans believed they had a moral duty to fight for oppressed peoples in Europe. There were, Morse observed, “other motives than that of curiosity, or of mere sympathy with foreign trouble, that should arouse our solicitude in the fearful crisis.” Indifference and intervention were not the only options open to the American people. Morse particularly rejected the idea that the United States should be militarily involved in Europe’s conflicts. The American republic was “happily separated by an ocean-barrier from the great arena where the physical action of this bloody drama is to be performed.” Geopolitical isolation meant that Americans were “secure from the immediate physical effects of the strife; but we cannot remain unaffected by the result.”

Sympathy, Morse observed, however high-minded, did not create policy imperatives. Americans could safely be ignorant both of cause and result of “European wars arising from the cravings of personal ambition, from thirst for national glory, from desire of territorial increase, or from other local causes.” But in the war of opinion, “in a war of principles, in which the very foundations of government are subverted, and the whole social fabric upturned,” Americans would not be “uninterested in the result.” American principles were not “bounded by geographical limits. Oceans present to them no barriers.”

Nevertheless, they would not feel compelled to fight for abstractions. The ultimate battles for human liberty would array “despotism throughout the world, whether in the iron systems of Russia and Austria, or the scarcely less civilized system of China” against “pure American freedom in the United States, or in the mixed systems of Britain, France, and some other European states.” This remained a world of nations. Liberal nationalist and liberal democratic movements, argued Morse, “should not pass unheeded by Americans.” Observation and sympathy, however, did not an intervention make.

Non-intervention remained a watchword of American liberalism well into the 20th century. Sympathies and material aid from citizens was encouraged, but the United States would not, in the words of John Quincy Adams, go abroad in search of monsters to destroy. Robert Kagan argued in his Dangerous Nation that the United States’ unwillingness to intervene stemmed from a lack of self-awareness. The United States, he argued, was a danger to autocracies, and the American republic needed to act like it. American history wasn’t actually about isolationism or cities on hills, but instead about a history of idealistic and materialistic expansion, not caution and passivity.

In fact, Morse and his era were neither passive nor interventionistic. The Early Republic shows the middle way between interventionist excess and unfeeling indifference that would benefit the United States in the 21st century, when both idealistic enthusiasm for liberalism or apathetic responses to tyranny might both lead to a more dangerous world.

Miles Smith is visiting assistant professor of history at Hillsdale College. His main research interests are 19th-century intellectual and religious history in the United States and in the Atlantic World. You can follow him on Twitter at @IVMiles.