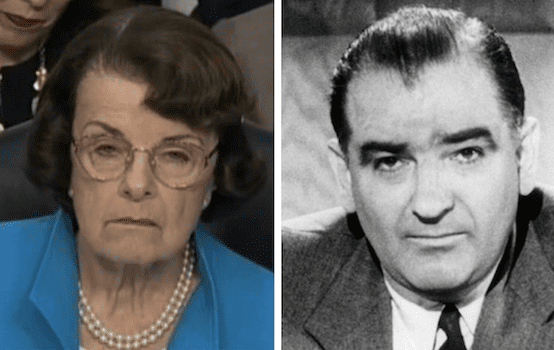

Dianne Feinstein and the Joe McCarthys of Our Time

Back in 1953, in the early months of the Dwight D. Eisenhower administration, the new president found himself in a political minefield related to his nomination of Charles E. (“Chip”) Bohlen to be U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union. The unfolding political drama tells us something about how we used to do things in America as opposed to how we do them today. One example is President Trump’s nomination of Judge Brett Kavanaugh to become a Supreme Court justice. Human nature having not changed, there were people of solid character back then as well as people of low character, the same as today. The big difference between the two situations lies in the level of political civility that reigned when politicians grappled with a potential scandal.

Bohlen was an acknowledged Soviet expert and a dedicated career diplomat who nonetheless had some bitter enemies inside and outside government. This was, remember, the height of the so-called McCarthy era, named after Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy, the fiery anticommunist pugilist who had placed at the center of politics the question of whether domestic communists were undermining America’s posture towards the Soviet Union.

Though a Republican, Bohlen was identified with the Democrats’ internationalist establishment. In those dark days of Cold War anxiety, conservative partisans delighted in attacking this establishment as a hotbed of domestic fools and villains responsible for the sad state of the world.

Worse, Bohlen had been at the 1945 Yalta Conference, site of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s secret agreements with the Soviets over the postwar map of Europe. Republicans believed these had sealed the tragic fate of Eastern Europe and fostered the Soviet threat to the West. The ongoing debate over Yalta was bitterly partisan.

All this amounted to a political firestorm that threatened to engulf the Eisenhower administration in its tender early phase. Perhaps Bohlen could have doused the flames had he criticized the Yalta agreements during his testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. But he believed they were in the country’s interest—and probably the best deal Roosevelt could have gotten from the Soviets’ Josef Stalin at the time based on the alignment of military forces in postwar Europe. He brashly refused to criticize Yalta, and the fat was in the fire.

Enter the masters of the Senate ambush—Republican McCarthy and his Democratic sidekick, Senator Pat McCarran of Nevada. Before Bohlen’s nomination was sent to the floor, the committee had focused on his views; now the ambush specialists turned to his character.

A whisper campaign began. The FBI’s investigative files, it was suggested, contained damaging information about Bohlen’s homosexual proclivities (considered disqualifying at a time when most gay people kept their sexual preferences in the closet). The rumors also hinted at possible loyalty questions. In those days, FBI files weren’t routinely passed around to various senators and their staffs to be leaked to the news media at strategic moments. But for the likes of McCarthy and McCarran, even suppressed investigative files had their political uses.

McCarthy called on Bohlen to take a polygraph test to refute the vague allegations swirling around the Capitol. McCarran attacked Eisenhower’s new secretary of state, John Foster Dulles, for suppressing the FBI information. He should come to the Hill, the wily senators suggested, and testify under oath as to why he wouldn’t allow public scrutiny of this important information.

At this point, Ohio’s influential Senator Robert A. Taft entered the fray. Taft hated Yalta and never shrank from using its symbolic significance for political advantage in foreign policy debates. But more than Yalta he hated the character assassination he saw unfolding on the Senate floor. He initiated a counterattack.

“Mr. Dulles’ statement not under oath is just as good as Mr. Dulles’ statement under oath, as far as I am concerned,” declared Taft. He then proposed a compromise: a senator from each party would inspect the FBI files and report back to the chamber on any pertinent character information they contained. The compromise was accepted, and Taft joined Alabama’s Democratic Senator John J. Sparkman on a mission to FBI headquarters. When they returned after three hours of study to report that the files contained no disqualifying information, the battle was over. Bohlen was confirmed, 74-13.

You can’t prove a negative, as the logicians tell us. Taft and Sparkman never learned for sure whether Chip Bohlen was gay. But they did know that the suggestion of homosexuality was never proved, and so Bohlen’s nomination could not be derailed.

How very civilized, even quaint, all this seems as we contemplate the kind of politics practiced today. There are some striking similarities between the Bohlen story and our current drama regarding Kavanaugh. These include: the focus on character matters after opponents failed to prevail on the nominee’s views, the late hit, the use of allegations that can never be definitively disproved, and the lack of regard on the part of the character assassins for the reputation of the man at issue.

But there are some big differences also. These mostly center on the prevailing mores and protocols of Senate behavior. If there are allegations that could prove damaging, they must be investigated. But most senators in Bohlen’s day knew they didn’t want a messy public battle, with the likes of McCarthy and McCarran wielding their big pikes. And consider the level of collegial trust that undergirds this story. When Taft and Sparkman returned with their report, the vast majority of senators instantly accepted their veracity. There was honor among colleagues, and it was understood that in delicate matters involving the reputations of public men, a central aim was to keep the McCarthys and McCarrans from running rampant through the halls of discourse.

Today the McCarthy/McCarran characters are given free rein, and no one can curtail their destructive romps. The leading McCarthy/McCarran figure in today’s unfolding drama is California’s Democratic Senator Diane Feinstein, who embarked on the most destructive approach she could conceive of in handling an allegation that was unproved and probably unprovable. She sat on the information throughout the committee process, then slipped it into the political maw. Her maneuver was designed to preserve for her a fig leaf of integrity while drawing into the public fray a woman who had said she didn’t want her name revealed. Then she sat back and watched the braying hounds attack.

As of today, we don’t know what actually took place between Kavanaugh and his accuser, Christine Blasey Ford, at that unsupervised teenage party 36 years ago, and we probably never will. Ford hasn’t given us much to go on—no date, no address, no identification of who owned the house, no witnesses (except one, who denies that the sexual attack took place), no recollection of how she got to the party or got home, no contemporaneous revelation of what happened even to her closest friends.

None of this is to impugn her honesty or the veracity of her story. But that story is unsubstantiated, and unsubstantiated allegations shouldn’t derail the course of Senate business. That was well understood in the Senate of 1953, and the result was a discreet and proper and civilized effort to adjudicate the matter without a lot of civic breakage. These days, civic breakage seems to be the name of the game.

Robert W. Merry, longtime Washington, D.C. journalist and publishing executive, is a writer-at-large for The American Conservative. His latest book is President McKinley: Architect of the American Century.

Comments