Susan Rice is Asia’s Worst Nightmare

There is a movement afoot to install Susan Rice as the decided nominee for Secretary of State. Rice last served in government as National Security Advisor to Barack Obama; at least one media report claims that he is personally lobbying Biden on her behalf. Such high-powered lobbying is necessary for a figure of Rice’s notoriety. The controversy that surrounded her handling of the 2012 Benghazi attack ensured that the Obama administration could not nominate her for any position that required Senate confirmation in its second term.

But she is not just persona non grata to Republicans. Reporting on her choice position in the wrangling over a Biden cabinet has stirred up a fury on the far left. Anti-war activists remember that Rice was a prime instigator of America’s catastrophic intervention in Libya, and are outraged that one of the principal authors of this disaster could today be the front-running candidate for any nomination.

But Rice’s problems extend far past her role in America’s Libyan calamities. This is an age where American diplomacy and international geopolitical maneuver is centered on what an older generation called the Far East—and Rice’s record on Asia is execrable. This record, and the appalling reputation it has given her in the region, should have long ago disqualified her from ever being considered as a proper selection for America’s chief diplomat.

The disgust Rice generates in Asian diplomatic circles was expressed with unusual frankness earlier this year by former senior Singaporean diplomat Bilahari Kausikan. In response to rumors that Rice was a leading candidate in Biden’s search for a running mate, the former diplomat waxed undiplomatic: “Susan Rice would be a disaster. She has very little interest in Asia, no stomach for competition, and thinks of foreign policy as humanitarian intervention. … [with Rice at the helm] we will look back on Trump with nostalgia.”

Look back on Trump with nostalgia! What a shock those words must be to the earnest Biden supporter! Have we not been warned that the Trump administration has irreversibly harmed America’s standing in the world? Have we not been told that Trump and his nationalist rhetoric have ruptured America’s alliances, disintegrated her international partnerships, and destroyed all possible chance of working in concert with foreign powers? How then could one of Asia’s most renowned diplomatic voices prefer another Trump term over the return of an Obama-era advisor?

To understand this dismal view of Rice, we must first pop some myths about American diplomacy in the age of Barack Obama and Donald Trump. Then we may proceed to Rice’s particular role in the worst mistakes of the Obama era. Liberals often portray the post-Obama era as an unmitigated diplomatic crisis, a time when time erratic foreign policy swings and “America first” rhetoric wrecked America’s ability to influence world affairs. There is truth to these accusations. But these accusations are far truer in some regions and with some relationships than others.

As Jeremy Stern has convincingly argued, the Obama administration’s foreign policy was defined not by its nominal “pivot to Asia” but by a deep commitment to the transatlantic relationship. Obama’s rosy reception by E.U. elites was established with his Nobel Peace Prize award and was cemented through his strong working relationships with David Cameron, François Hollande, and Angela Merkel. “The administration shared decision-making power with Europe on regional conflicts in Libya, Syria, and Ukraine,” Stern observes, “and on global issues like climate change and arms control. It saw and treated China’s seizure of the Scarborough Shoal as a far less significant event than Russia’s annexation of Crimea. It negotiated the Iran Nuclear Agreement not with the consent of local stakeholders … but with Germany and the United Nations Security Council.” Obama’s much ballyhooed commitment to multilateralism was a commitment to institutions and fora—like the European Union, NATO, and the U.N.—that privilege European interests and embody the values of the post-war transatlantic consensus.

It is little surprise that a Trump administration distrustful of multilateral organizations, disdainful of the technocratic ethos that Obama shared with officials in Berlin and Brussels, and fully willing to toss liberal shibboleths aside to pursue “deals” with authoritarian powers would cause waves of horror in European capitals. But wellsprings of horror in Europe were often sources of strength in Asia. In Asia, international politics moves to a different tune.

At the birth of the post-war consensus, Asian powers were colonies or recent conquests. They have far less invested in these transatlantic multilateral structures than Paris or Berlin. Asian elites are consequentially far less concerned with their erosion than their European counterparts. Nor are Asian publics especially enamored with Western European norms and values. European fear of nationalism has no purchase on a continent where political identity is shaped less by memories of the Western Front than by the glories of national revolt against Western imperialism. Many Asian powers, including several of America’s treaty allies, are lukewarm on liberalism. Trump’s diplomacy, focused on personal relationships with foreign leaders and framed as the simple pursuit of national interests, was not felt as a subversive force in Asia as it was in Europe, as it simply brought American diplomacy in line with existing regional norms. Obama-era foreign policy, which often took the guise of a supercilious liberalism carried out at a cold remove, warmed few hearts to the American cause.

Even a regional ally such as Australia, heir to the same liberal tradition as the United States and equally committed to upholding the cause of global democracy, often found itself distraught at the Obama administration’s willingness to trade out its interests and security for some phantom scheme of harmony with the People’s Republic of China. The Obama administration’s declared “pivot” to Asia was mostly rhetorical. Throughout Obama’s two terms, America’s diplomatic energy and military power was unmovably absorbed with crises in the Middle East. In contrast, the Trump administration’s focus on the ideological, intelligence, and military threat posed by growing Chinese power has put some fence-sitting Asian nations in a tough spot, but has been a relief to regional allies who feared that America lacked the focus or capacity to respond to China’s vaunting ambitions.

To America’s closest allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific, Susan Rice represents the worst aspects of Obama’s diplomacy distilled in human form. She is associated with a foreign policy approach anchored on European perspectives and values, a high-handed, holier-than-thou style of diplomacy, and a consuming focus on Middle Eastern crises that distracts and detracts from America’s declared commitments in the Asia-Pacific. But above all else, Rice has earned a well-deserved reputation as the senior American official most willing to sacrifice the interests of American partners to chase what Rice calls “expanded cooperation” with Beijing.

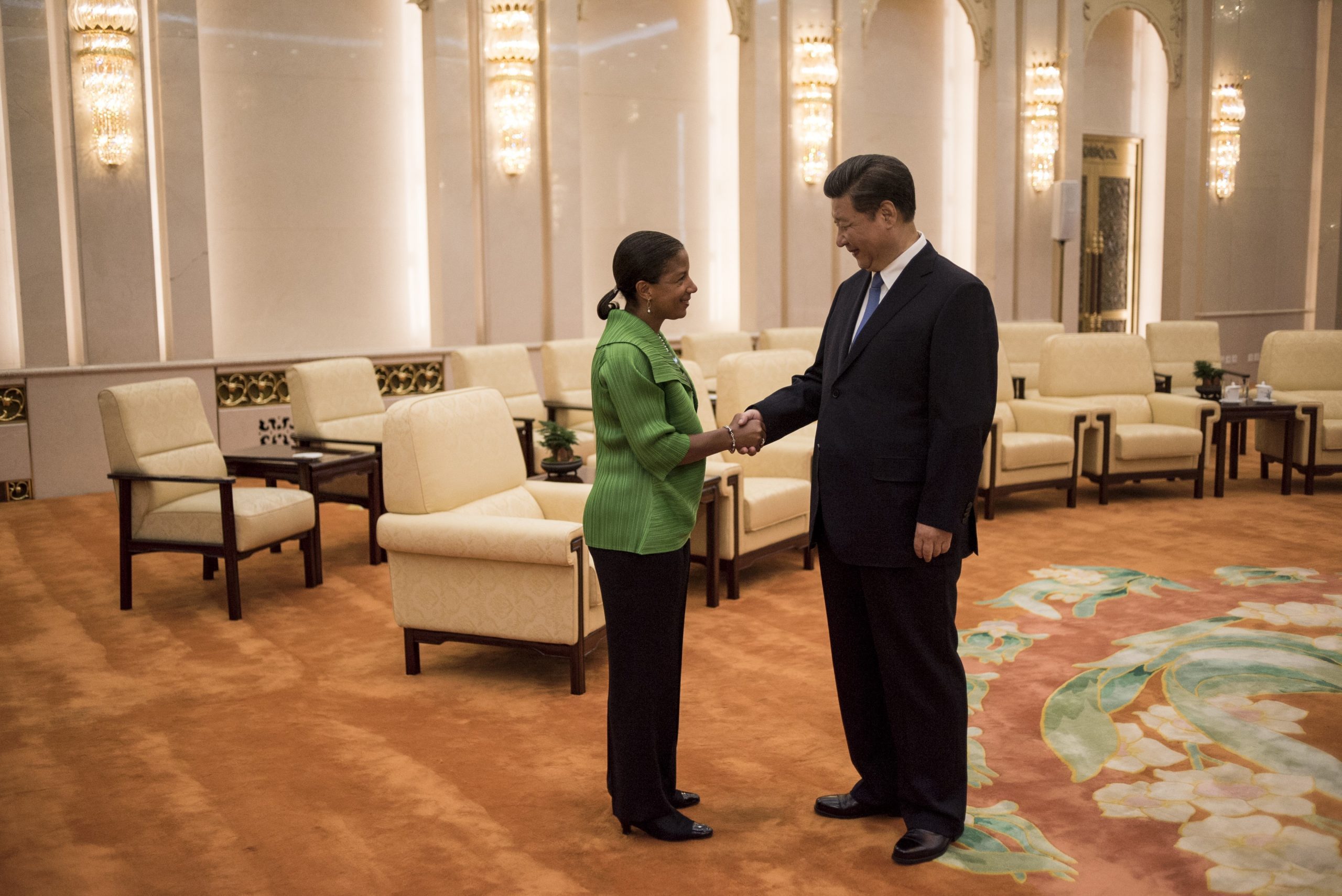

Susan Rice credits herself with a commanding role in the implementation of Obama’s China strategy. In her memoir Rice describes why she, as National Security Advisor, needed to take control of America’s relationship with China, instead of allowing another NSC “Principal” (like the Secretary of State) to take charge:

China has long preferred dealing directly with the White House on bilateral affairs . . . [and] given the complexity of the relationship, its many economic and strategic facets, and the need to ensure that multiple disparate agencies sing from the same hymnal, strong White House leadership makes sense. As NSA I embraced this responsibility.

This framing may seem innocuous, but its sentiments raise alarm bells across Asia. By elevating U.S.-China relations as the bilateral relationship in American foreign policy (Rice often describes it as “the most consequential bilateral relationship in the world”), the one realm of cooperation that demands continuous cross-domain coordination from the White House itself, Rice devalues America’s actual partners in the region. Taiwanese, Filipino, Australian, and Indian diplomats (to say nothing of their Singaporean, Thai, or Vietnamese counterparts) know that if all aspects of the China relationship are cross-linked, then their interests will always be traded out for better Chinese behavior with respect to Iran, North Korea, climate change, the cyber realm, or any other domain the Chinese decide to pull a tantrum over that week.

This framing is even more humiliating for the Japanese. It forces them into an undeserved second-class spot. Though Tokyo is America’s most important ally, the hub on which U.S. foreign policy depends, and a power more crucial to American-led financial and macroeconomic coordination than Beijing has ever been, Tokyo was not given the same bilateral access to the Obama White House that Rice arranged for the Chinese Communist Party. Susan Rice owned the China relationship; Japanese concerns did not command the attention of any of the Principals. Obama hardly spoke to Putin without first hearing Merkel’s take; the Japanese were given little input into American strategy for managing China.

Here again the Trump administration provides a surprising contrast. Trump’s team did not just recognize the significance of the Chinese bid for supremacy. They also recognized that any coherent response to the Chinese Communist Party’s plans must start with Japan. This was reflected in Trump’s personal performance. In an essay explaining how Japanese officialdom warmed up to Trump, one anonymous Japanese official describes the President’s priorities:

Trump has called [Japanese Prime Minister] Abe at every important occasion—before and after his meeting with Xi Jinping, for example, and as he planned his opening toward North Korea. According to media reports, as of May 2019, Abe and Trump had met 10 times, talked over the phone 30 times, and played golf 4 times. This volume of engagement, as measured in telephone calls, was already quadruple the number of engagements that Abe had with Obama [over both terms].

Before Trump, this sort of cooperation and engagement was reserved for the Chinese, favored European allies, and Middle Eastern countries then subject to American counterinsurgency campaigns. Rice’s autobiography reflects this focus. Of its 482 pages, only 13 cover China—most of which are spent celebrating the administration’s 2015 cyber agreement with Beijing (which never had a credible enforcement mechanism, was still not fully implemented at the end of Obama’s tenure, and was abandoned by the Chinese shortly after he left office) and the administration’s unsuccessful efforts to convince the communists to take a harder line against North Korea. But these 13 pages are a mountain compared to her sparse treatment of America’s Asian partners. Across the book, Japan and India are only given a few scattered mentions. The U.S.-Philippines relationship is reduced to a sentence. There is no entry for “Taiwan” in the index.

Rice boasts in her book that she “understands the interests and the idiosyncrasies” of the Chinese, but never demonstrates similar knowledge or concern with any other power in the region.

And they know it! “Susan Rice, who served as the Obama administration’s National Security Adviser, has been floated as a potential vice presidential candidate for Mr. Biden,” worried Tatsuhiko Yoshizaki, a prominent Japanese “America hand,” this spring. “Seeing the [return of the] name of the central figure of ‘Compromise-With-China’ [policy] will perturb the hearts of many of our officials.” In a column responding to reports that Rice is the likely nominee for Secretary of State, former Indian diplomat M. K. Bhadrakumar shares similar musings: “Frankly, these reports cause a sinking feeling . . . It is doubtful if [Rice] has any deep-rooted beliefs or convictions . . . [but] China would heave a big sigh of relief if Biden picks Rice as his secretary of state.” Lai I-chung, former director of the foreign policy program of the DPP, Taiwan’s ruling party, echoed these concerns in a recent interview. “What has Susan Rice written about China or Taiwan? The lack of the deeper understanding on the issue of Taiwan by Biden advisers is something that causes a lot of concern here.” Again and again we find Asian diplomats and analysts questioning Rice’s ability to understand their concerns or steel herself to stand up to the Chinese.

There is room for debate as to just how America ought to stand up to the Communist Party of China’s authoritarian designs. American allies and partners may push the United States to make commitments that are better for their interests than America’s. There is no reason we must give them all that they ask for. But the task of identifying where allied interests diverge from American ones, and the subsequent challenge of crafting coherent policy in the face of these divergent interests, requires a certain kind of diplomat—a diplomat who is respected by her foreign counterparts, has a crisp understanding of their political and cultural quirks, and can be trusted not to prioritize the neighborhood bully’s perspective over their own. Susan Rice is not that diplomat. Not in Asia.

Biden—and the Congress that confirms his personnel nominations—must decide how much affairs in Asia really matter. Far from reassuring our allies, nominating Susan Rice—the Obama official most notorious for prioritizing Chinese complaints over allied entreaties, and Middle Eastern interventions over Asian affairs—would signal to America’s partners that the contest for the future of the Asia-Pacific region does not matter much to America at all.

Comments