Psychoanalyzing the President

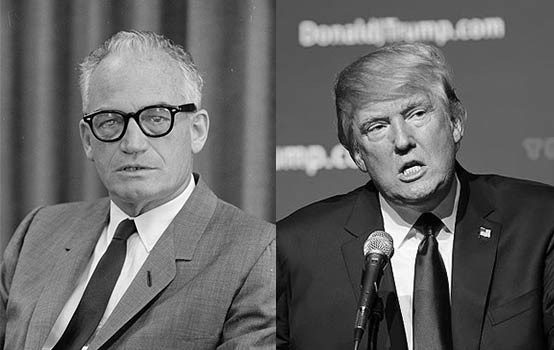

Over 50 years ago, when conservative Republican Barry Goldwater ran against sitting President Lyndon Johnson, several prominent psychologists and psychiatrists made the same claim: that he was not merely a conservative extremist but a mentally unstable wing-nut not unlike cinema’s Dr. Strangelove—someone who might even “push the button.”

Indeed, what is still perhaps the ugliest political attack ad in history—the “Daisy Ad”—directly took up this theme, showing a carefree little girl playing with a flower as an ominous voice counted down to an atomic-bomb attack. Shortly thereafter, Johnson was reelected in what was then the biggest landslide in American history. The attack was made even more outrageous in retrospect when, just months after running as the “peace” candidate, Johnson went full-throttle into the Vietnam War in the summer of 1965.

After this, major medical, psychological, and psychiatric organizations cemented what was called “The Goldwater Rule,” prohibiting experts from trying to “diagnose” high-level political officials they had never met. But Donald Trump’s late-night Twitter rampages and his insecurity about “size”—whether that of his hands or of his crowds on Inauguration Day—have led some to flout the rule.

An especially memorable and fierce attack came from Twitter superstar and Daily Kos columnist “Propane Jane,” who is a licensed and practicing M.D. and psychiatrist in Texas in her real life. In her article “Instability in Chief,” Propane Jane indeed lights a fire under President Trump. After documenting signs of serious decline, she calls for a full-on psychological intervention.

It’s unlikely (to put it mildly) that a sitting president could be forced to undergo a psychiatric evaluation, and the odds of Trump consenting to such a thing seem somewhere between slim and none. Yet Congress does have the power of subpoena, and has used it to force past presidents including Richard Nixon and Bill Clinton (as well as former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton) to give accountings of things they’d have rather avoided talking about. Democrats have already introduced a bill that would require the White House to have an in-house psychiatrist. And if Trump’s signature outbursts do cause a serious international or economic incident, voters may feel compelled to pressure their representatives to insist on an evaluation.

Another, even more drastic solution comes from USA Today’s Gabriel Schoenfeld:

[The 25th Amendment] sets up two paths for dealing with an incapacitated president who cannot or chooses not to declare himself unfit. The determination could be made by the vice president together with “a majority of either the principal officers of the executive departments,” or by some “other body as Congress may by law provide.”

This line of attack has a longer and richer history than many realize, one that extends far beyond Goldwater and now Trump. Nearly every recent president has confronted rumors of mental illness or at least Freudian speculations.

While he, his predecessor Franklin D. Roosevelt, and his successor Dwight Eisenhower are all fixtures on most historians’ presidential top-10 lists, not everyone was wild about Harry S Truman. Leftist historians like Charles Beard and William Appleman Williams, and later authors including Gore Vidal, Howard Zinn, and Oliver Stone, accused Truman of being an inferiority-complexed “mama’s boy.” They believed that Truman dropped the atom bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and exacerbated the Cold War largely out of a wish to seem like a “tough guy.”

Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon never forgot their impoverished, hardscrabble upbringings—Johnson in rural, World War I-era Texas and Nixon in small-town, undeveloped Orange County as one of many sons of a shopkeeper father and a devoutly religious Quaker mother. Both were often coarse and tasteless, and in the popular imagination, both men’s downfalls were a direct result of their anger issues and paranoia.

Ronald Reagan was psychoanalyzed mostly in retrospect, given that less than six years after retiring he came out of the closet about his Alzheimer’s diagnosis in a “farewell letter.” But it was widely rumored that Reagan was already “showing signs” of the disease when he was still president, particularly in his second term, giving rise to rumors and conspiracy theories about who was really “in charge” during those years. A biography of Reagan called Dutch, released in 1999, even added fictional characters to try to flesh out Reagan’s essence.

Before Hillary, the most important figure in Bill Clinton’s life was unquestionably his mother Virginia, an indomitable, swing-dancing, rock-and-rolling, colorfully dressed Southern nurse anesthetist who was married four times (and widowed three) before her death at age 70. A controversial book by clinical psychologist and Johns Hopkins lecturer John D. Gartner, titled In Search of Bill Clinton, revealed that a small-town nickname for Virginia (whose maiden name was Cassidy) was “Hop-along Cassidy,” a reference to a famous Western movie hero, because she would allegedly “hop into bed with any man who came along.” Virginia was known for her hair and makeup and her irresistible allure well into middle age. And many people—including Hillary Clinton herself—have attributed Bill’s later issues to childhood abuse of an unspecified nature.

Oliver Stone’s Josh Brolin-starring biopic W (made in the closing year of the George W. Bush government) was hardly the only book or movie to suggest that “Dubya” had a Freudian father complex. While both Bushes have denied this, rumors suggest that the younger Bush’s stubborn, hard-line conservatism was a result of his being not merely jealous but consumed by resentment and feelings of inferiority toward his father, President George H.W. Bush.

Barack Obama’s first book, published in 1995, was called Dreams From My Father, although what Obama’s many Tea Party critics don’t get is that the title was meant to be ironic. His Kenyan father divorced his mother, anthropologist Ann Dunham, and returned to Kenya shortly after he was born, never to return except for a one-time visit when little “Barry” Obama was ten. But as The New Republic revealed, Obama’s mother and “well-meaning white grandparents” constructed a “myth for a fatherless black child to live by” of a superhero-strong, philosopher-wise absentee father, brimming with life lessons and wisdom.

Donald Trump may be (in many people’s opinions) the worst, in other words, but he’s hardly the first president to inspire serious questions about his psychological fitness and health.

Telly Davidson is the author of a new book on the politics and pop culture of the ’90s, Culture War. He has written on culture for FrumForum, All About Jazz, FilmStew, and Guitar Player, and worked on the Emmy-nominated PBS series Pioneers of Television.

Comments