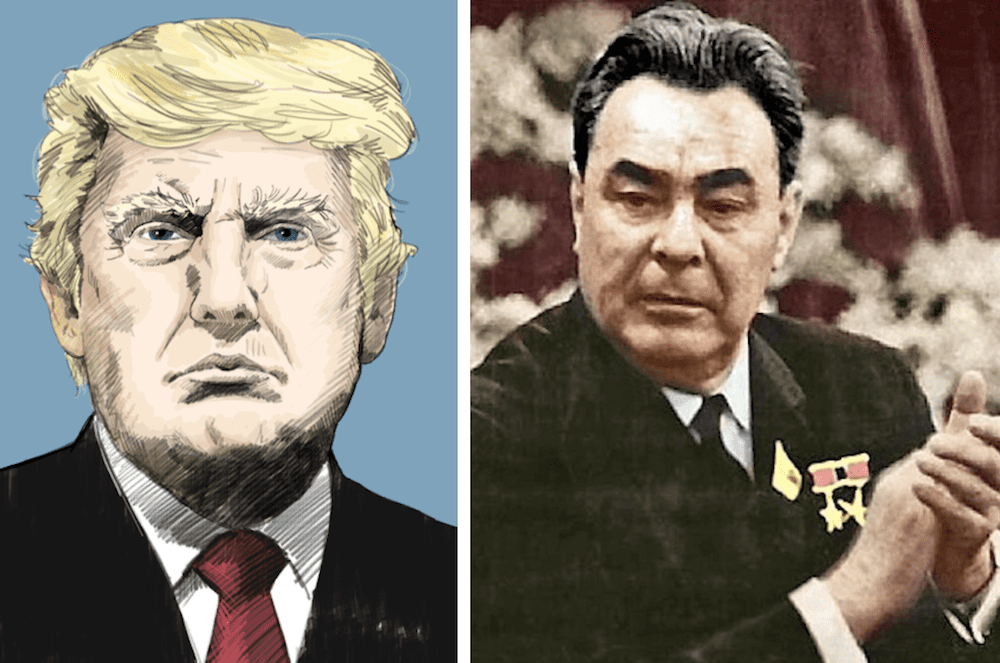

Party Leaders: Comrade Leonid, Comrade Donald

The National Security Archive, an under-appreciated jewel in the crown of the George Washington University, has now made available in English translation its latest volume of Anatoly S. Chernyaev’s journal. A long-time adviser to senior Soviet officials, Chernyaev was a diarist in the tradition of the American diplomat George Kennan—shrewd, uncompromisingly honest, both a patriot and something of a romantic.

This new volume begins in January 1980. The month prior, the Red Army had intervened in Afghanistan, touching off a sequence of events destined to culminate in the dissolution of the Soviet Empire and the USSR itself. In his diary, Chernyaev acknowledged that the Soviet Union was already in a state of advanced political, economic, and moral decay. The problem started at the top, Chernyaev describing party leader Leonid Brezhnev as “completely senile.” (p. 1)

While little evidence to exists to suggest that President Donald Trump suffers from senility, the resemblance between the Soviet leadership in the Age of Brezhnev and America’s in the Age of Trump is unmistakable and more than a little troubling. Here are some of Chernyaev’s more telling observations.

On the supreme leader’s work ethic: “He does not read anything himself anymore, except for short public speeches. Texts are read aloud to him, and only the ones that someone deems necessary within the ‘sparing regimen’ he is on to avoid worrying him.” (2)

On the leader’s decision-making: He “adjusts to others’ opinions and acts as if he came up with it himself.” (14)

On the leader’s inner circle of advisers: “Senility is affecting the entire structure, the mechanism of top-level power, due to the senility of its leader… Most things are done to cater to One man—and to disturb him as little as possible. …. The entire elite appears in the eyes of the people as money-grubbers – material and spiritual plunderers of the country. ” (6, 18, 31)

On the regime’s credibility: “Our moral-ideological prestige is below any conceivable level. It keeps falling due to our lies. We keep lying to our people, to ourselves, to all other peoples and parties. And whatever does not fit the lies, we consider anti-Soviet, enemy machinations, or revisionism. (43)

On the leader’s party: “Glorification of Brezhnev was in full-force at the Plenum. Everyone began with frothy enthusiasm about Leonid Ilyich’s speech—the deepest Marxist-Leninist document, a plan of action for the entire historical period, permeated with Leninist wisdom and a scientific approach, genuine Party-spirit and so forth; it inspires, elevates, we now have a real Leninist strategy. Everyone thanked ‘our Leonid Ilyich,’ everyone committed to him personally to fulfill the tasks he assigned. The glorification reached its moronic climax in Brezhnev’s own speech.” (46)

On the Afghanistan War: “Afghanistan is like a sore that eats away at public consciousness and international life. … Whose idea was this? … What for? Who is supposed to answer for this? … It is pointless to look for logic. We pour several million into Afghanistan daily, and daily we pay with the blood of our soldiers. What for—nobody can explain.” (4, 5, 48)

On the possibility of further miscalculation: “It’s scary to think about what would happen if our side decides to take that step. And they might, because the person making the decisions does not have the necessary information (he cannot even read what’s at his fingertips) to assess the consequences. But even if he was physically capable of reading everything, he would hardly be able to comprehend the significance of his decisions and actions.” (49)

On dying for one’s country: “The main thing that once again stunned me: a war memorial near the church—the standard figure of a woman with an olive branch in her hands, a wall a little distance behind her with names of the fallen. I read them, crying. … One hundred fifty people. That’s just from one village! An entire marching company. For some reason, in moments like these I always feel bitterness towards Brezhnev & Co.” (52)

On the durability of the existing order: “We’ve had enough for our time! Russia won’t collapse in five-six years, so why thump our chest, why attempt risky changes?! And the people will endure—they have no other options anyway, plus, ‘they aren’t hungry.’ … It seems our leaders made up their minds: ‘Fuck them all, let them say whatever they want, they won’t do a thing against us!’” (45, 52)

On the advantages of being a great power: “Because we are Russia, we can stay in such a crisis and idiocy for decades.” (42)

The final diary entry for the year was dated December 26, 1980. Eleven years later to the day, the seemingly impossible occurred: The Soviet Union ceased to exist.

Andrew Bacevich is president of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft.

Comments