Neil Gorsuch Catches a Hail Mary for the Constitution

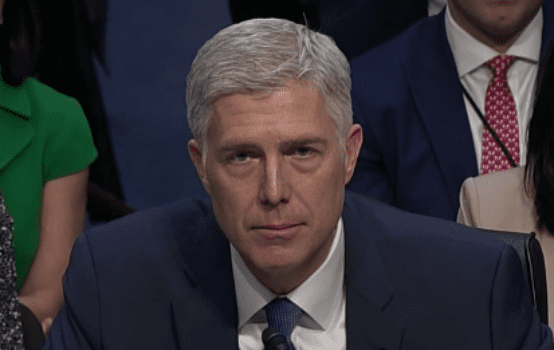

Last week, the Supreme Court took a major step toward rolling back one of the most unconstitutional features of our federal government: the over-delegation of lawmaking power to the executive branch and administrative agencies. In Gundy v. United States, the Court took a relatively obscure case filed by a public defender—one with no support from amicus briefs or popular commentary—and revisited the nondelegation doctrine, a crucial but largely forgotten part of our Constitution. And while we can’t know for sure, this turn of events was likely due to the actions of Justice Neil Gorsuch.

In his second term, Gorsuch is again showing how a principled commitment to the Constitution can help reshape the Court into a more nonpartisan and just institution.

Herman Gundy ultimately lost his case. Justice Elena Kagan’s majority opinion maintains the status quo of allowing Congress to abdicate its responsibility to pass laws. Justice Samuel Alito gave Kagan a fifth vote, though he also unequivocally voiced his support for revisiting the nondelegation doctrine: “If a majority of this Court were willing to reconsider the approach we have taken for the past 84 years, I would support that effort.” That’s a big deal, and it’s an invitation to litigators to bring forward another nondelegation case.

How Gundy’s case got to the Court, however, is an interesting story.

Gundy was convicted under Maryland law for sexually assaulting a minor. His conviction happened before Congress approved the Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act (SORNA) in 2006. But SORNA requires registration even for sex offenders who were convicted before it was passed, and lets the attorney general define which past offenders have to register, certainly a broad delegation of legislative power to the executive branch. But that happens all the time, and as Alito pointed out, it’s been 84 years since the Supreme Court held that Congress had over-delegated its constitutional responsibilities.

When Gundy didn’t update his status upon moving to New York, he was prosecuted for violating the act. He filed his appeal to the Supreme Court in forma pauperis, which is a request by an indigent defendant to waive the usual filing fees. The Supreme Court gets between 7,000 and 8,000 petitions per year, and about two thirds are filed in forma pauperis, often from prisoners and often pro se (representing yourself). Gundy’s chances weren’t good.

Here’s where things get interesting: Gundy’s petition to the Supreme Court was a Hail Mary pass intended for Gorsuch, and Gorsuch caught it.

Gundy’s petition raised a few reasons why the Court should take his case. It is standard practice to ask the Court to review a variety of questions, and attorneys usually put their best issue forward first, which for Gundy seemed to be the fact that when he “moved” to New York, he was in the custody of the Bureau of Prisons, having been transferred to a halfway house in the Bronx. Gundy’s attorney made the sensible argument that, when someone is in custody, they shouldn’t have to register, nor should they have to register when they’re forced to move.

Those two issues seemed on solid ground. The Hail Mary pass was the third one: whether Congress improperly delegated legislative authority to the attorney general. It has been nearly a century since a delegation challenge worked, which is why this was such a long shot. Understandably, Gundy’s lawyer devoted only the last page and a half of a 20-page brief to the issue. But she included an important citation: a concurrence by then-judge Gorsuch of the Tenth Circuit pointing out that SORNA has some over-delegation problems.

Despite having only a page and a half of briefing and no support from amici curiae briefs, certiorari was granted on the delegation question alone. That shocked Court watchers who believed that the nondelegation doctrine had long been put to pasture.

The case was argued on the first day of the term, October 2, and decided only last week, an unusually long time. Justice Brett Kavanaugh had not yet been seated, so an eight-justice Court heard the case. The behind-the-scenes story probably revolved around Alito deciding how to vote, specifically whether he would vote with Gorsuch’s three-justice dissent and create a 4-4 tie, which wouldn’t have resulted in a controlling opinion and would have more or less wasted everyone’s time. As we saw, while stating his reservations, he decided to break the tie.

Ultimately, Gorsuch not only caught the pass from the petition, he spiked the ball with his dissent. The nondelegation doctrine ensures “that only the people’s elected representatives may adopt new federal laws restricting liberty.” Allowing the attorney general to define which sex offenders must register under SORNA endows “the nation’s chief prosecutor with the power to write his own criminal code governing the lives of a half-million citizens.” But the case isn’t about sex offenders; it’s about liberty, because “if a single executive branch official can write laws restricting the liberty of this group of persons, what does that mean for the next?”

Gorsuch’s dissent was joined in full by Justice Clarence Thomas and Chief Justice John Roberts. Alito, as we’ve seen, is open to reconsidering the doctrine. The only question is how Kavanaugh would vote, but it seems likely he’ll be onboard. In the next case, we could see 84 years of constitutional abdication rolled back, all because of a petition filed in an obscure case that effectively appealed to Gorsuch’s principled adherence to the Constitution.

Trevor Burrus is a research fellow in the Cato Institute’s Robert A. Levy Center for Constitutional Studies and editor-in-chief of the Cato Supreme Court Review.

Comments