Why You Don’t See Napoleon’s Wars Taught Like This Anymore

The Napoleonic Wars: A Global History, Alexander Mikaberidze, Oxford University Press, 960 pages

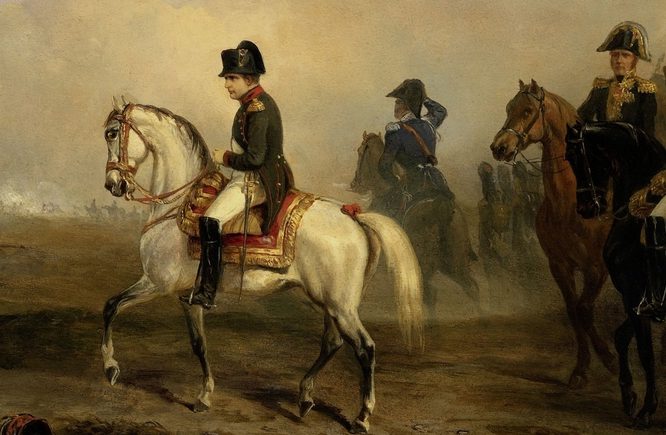

In this thousand-page tour de force, researched in over a dozen languages with 189 pages of notes, the exceptionally talented Georgian-American historian Alexander Mikaberidze, a professor at Louisiana State University Shreveport, revisits a foundational conflict in the modern world, the veritable “world war” unleashed by the French Revolution and dominated by the towering figure of Napoleon Bonaparte.

Recalling that tempestuous era normally evokes disciplined blue columns furiously marching about Europe under the French tricouleur until finally bested by Russian blizzards and iron dukes. Mikaberidze tells a bigger story. Far from being a mere European conflict, the Napoleonic wars had global significance, with each big powerplay reverberating far beyond the devastated continent’s rocky shores. France fought its coalitions of enemies not just on the western edge of the vast Eurasian plain, but in the jungles of India, on the isles of the Caribbean, in Asian royal courts, and just about everywhere in between, including the deep blue sea.

Reacting to Napoleonic conquests in Egypt, to take only one example, motivated the British to set defense protocols for India that lasted for the next century, laying the foundations for the “Great Game” for inner Asian domination. Napoleonic fallout on the high seas—increasingly desperate attempts to control the Atlantic trade, the underpolicing of North African pirates by distracted European navies, worries about the security of French possessions in the new world—all played determining roles in the foreign policy of early national America, which, among other triumphs, doubled in size by acquiring the Louisiana Territory from a France unable to hold it, sent the Marines to Tripoli to neutralize a commercial threat, and dispelled British attempts to retain hegemony in North America.

French intrigues at the Ottoman court ensnared Russia in a draining war over the Balkans just as Napoleon moved to consolidate his fresh domination of Eastern Europe. Persia played a delicate balancing act between France and its adversaries, only to be humiliated and start down a long, fraught path of tension between tradition and Westernization. None of this takes away from the author’s masterful accounts of the great European campaigns, a risky endeavor given that virtually no other humans have been more widely written about than Napoleon. Mikaberidze, however, contextualizes them in a global context that provokes highly original assessments few have otherwise considered.

That Mikaberidze could achieve this feat in modern American academia bucks one of the historical profession’s most lamentable trends—its steady reduction of military and what used to be called “diplomatic” history to virtual nonexistence. The tenured apparatchiks who nurse university-based history as it enters its death throes just don’t like those fields. Their “maps and chaps” approach is too centered on elites for their plebian sensibilities. Document-based empiricism leaves no room for the identities, feelings, and other “subjectivities” they privilege. Studying martial triumph and tragedy veers worryingly toward patriotism and national pride. And they find these high political fields so obnoxiously full of those troublesome white males. Even leftists who engage this taboo material—to discredit imperialism or try prove that America started the Cold War, for example—now sheepishly find themselves marginalized in a warped academic culture that just doesn’t want them around.

In top schools these fields are barely taught and openly derided by “scholars” more inclined to study the people who scrubbed foreign ministers’ toilets than they are to study foreign ministers. Once one of the top two or three undergraduate majors, the number of new history B.A.s has plummeted by nearly 50 percent in just the last decade, following on a gentler decline over the previous several decades. The idea of pursuing the discipline at the graduate level has now become literally laughable among the best and brightest, who are justifiably put off by administrative caprice, stagnant salaries, and an ever shrinking job market. Merely taking history courses as currently taught is downright offensive to large numbers of young people who object to the idea that they and their country are little more than bad products of scabrous racial conflict.

Two generations ago, a scholar of Mikaberidze’s caliber and acumen would have commanded a prestigious Ivy League appointment, trained dozens of brilliantly engaged minds who would have gone on to impressive careers of international significance, and influenced decisions at the highest levels of government. Thanks to the historical profession as it currently operates, he sadly has no prospects of that. We can only hope that this worthy scholar’s academic perch will remain comfortable enough for him to continue to produce books of exceptional quality and insight that will inform educated publics who rely less and less on the decaying university model of humanities education.

Paul du Quenoy is president and publisher of Academica Press.

Comments