Buchanan on Nixon: Triumph and Tragedy

Had Richard Nixon confined himself to a single term and stepped down in January 1973, Patrick J. Buchanan writes of the man he served for eight years as senior adviser, speechwriter, confidant, and friend, he now would rank “as one of the great or the near-great presidents.” Writing in his 13th book (and his third on the Nixon presidency), the feisty commentator and former presidential candidate adds that, while he opposed some of his mentor’s domestic policies and foreign initiatives, he believes that “Nixon’s first term was undeniably one of extraordinary accomplishment.”

He’s right, and this book makes the case with the author’s characteristically muscular and vivid prose. When Nixon assumed office in 1969, he took command of a nation wracked by race riots, burning cities, assassinations, campus turmoil, and trembling university administrators living in fear of various New Leftists who, when they weren’t tearing down the campuses, made them centers of their disruptive operations. The unrest was fueled in great part by the Vietnam war and its increasingly mindless escalation, a gift to the new administration from two preceding Democratic presidents and their think-tank advisers—the so-called Best and Brightest.

Nixon was hired by the American people to end that seemingly endless war, dropped into the lap of the nation by LBJ, and to put down the insurrection at home. He carried out his mandate, and did so against extraordinary odds. The Democrats enjoyed congressional majorities in both houses, while out in the country, especially in the coastal cities with concentrated media outlets, the hostility was intense and the attacks unrelenting. By way of illustration, it wasn’t much different from today, when news organizations such as the Washington Post and the New York Times, when not bewailing the plight of the transgendered or some other exotic branch of the New Democratic coalition, seem dedicated on both their news and editorial pages to bringing down Donald Trump, however flimsy the charges.

Washington, DC, in late 1969 wasn’t much different. On November 3, two weeks after a massive demonstration aimed at ending the war immediately, and two weeks before a larger and more radical planned demonstration, Nixon delivered a nationally televised speech in which he reviewed the history of the war and summarized his plans for ending the U.S. role with honor while allowing South Vietnam to determine its own fate. Of course, South Vietnam’s fate was sealed by the North, but if it hadn’t been for Watergate and the consequent refusal of Congress to respond when North Vietnam mounted its all-out conventional invasion of the South, the Nixon approach may well have succeeded—and in fact was succeeding before Congress turned its back.

But in November 1969 Nixon’s hopes seemed at least feasible, though his delicate policy seemed to be hanging by a thread. In his November 3 speech, which Buchanan tells us the president wrote himself, Nixon brilliantly directed his words to what he called “the Silent Majority” (Buchanan’s phrase). He told the nation: “I have chosen a plan for peace. I believe it will succeed. If it does succeed what the critics say won’t matter. If it does not succeed, anything I say then won’t matter. … I have initiated a plan which will end this war in a way that will bring us closer to that great goal to which [Woodrow] Wilson and every American president has been dedicated—the goal of a just and lasting peace.”

The speech, writes Buchanan, “rallied the nation, with 70 percent of Americans registering their approval of the president’s stance on Vietnam.” But over at the powerful television networks (just three of them back then), the anchors and correspondents were “universally derisive.” Buchanan writes: “NBC wheeled out Averell Harriman, LBJ’s negotiator with North Vietnam, who had produced nothing in a year in Paris, and whose 1962 treaty for the neutralization of Laos had ceded the Ho Chi Minh trail to Hanoi.” Not surprisingly, Harriman “picked apart the President’s policy.”

Nixon, though elated with the response of the Silent Majority, fumed at the network commentary. White House chief of staff H.R. (“Bob”) Haldeman suggested a massive letter-writing campaign. Buchanan considered that a massive waste of time. “Scores of millions had seen the President’s speech on the networks,” he writes, “and scores of millions had seen the critical commentary and analysis that followed. If ever there was a time to launch a preemptive strike on the networks and news media, this was it.”

Two days after the speech, Buchanan sent to the president a memo designed to “turn the smoldering hostility between the White House and the networks and national press into a war that would last until the day that Richard Nixon resigned the presidency.” Indeed, adds the pugilistic commentator, it’s a war “that continues until this day.”

Buchanan considers that memo to be among the most consequential he ever wrote, resulting as it did in a major speech on the responsibilities of the media, a classic of its kind, to be delivered by Vice President Spiro Agnew on November 13 at a Midwest Regional Republican meeting in Des Moines, Iowa. Buchanan had become friendly with Agnew during several speaking sorties, and on one of them, to New Orleans, the vice president attacked “an effete corps of impudent snobs” who characterized themselves as intellectuals. Many attributed the phrase to Nixon speechwriter William Safire, but Agnew told me years ago that he had come up with it himself, and Safire subsequently confirmed it.

Buchanan wrote four drafts of the Des Moines speech. When he sent the final one to Nixon, the president went over it with pen in hand, line by line. “As he quietly read,” writes Buchanan, “I heard Nixon mutter, ‘This’ll tear the scabs off those bastards.’” And it did. Just a few days before, said Agnew in Des Moines, as network cameras rolled,

President Nixon delivered the most important address of his administration, one of the most important of the decade. His subject was Vietnam. His hope was to rally the American people to see the conflict through to a lasting and just peace. … When the President completed his address … his words and policies were subject to instant analysis and querulous criticism. The audience of seventy million Americans … was inherited by a small band of network commentators and self-appointed analysts, the majority of whom expressed, in one way or another, their hostility to what he had to say. … The purpose of my remarks tonight is to focus your attention on this little group of men who not only enjoy a right of instant rebuttal to every presidential address, but more importantly, wield a free hand in selecting, presenting and interpreting the great issues. … What do Americans know of the men who wield this power? To a man, we know that these commentators and producers live and work in the geographical and intellectual confines of Washington, D.C., or New York City. … Both communities bask in their own provincialism, their own parochialism … read the same newspapers and draw their political and social views from the same sources. Worse, they talk constantly to one another, thereby providing artificial reinforcement to their shared viewpoint.

This small group of men, Agnew told the nation, had achieved monopoly control of the most powerful means of communication known to man and were exploiting this power to shape national opinion to advance their own ideological agenda.

The Des Moines speech “was a national sensation,’’ writes Buchanan. “Scores of thousands of telegrams, phone calls, and letters poured into the White House backing the Vice President—and into TV stations and the networks denouncing their biased coverage.” Agnew was put on the cover of Time and Newsweek, becoming overnight a household name—a tribune of Middle America, the voice of the Silent Majority.

Soon after, Agnew gave the same treatment to the New York Times and the Washington Post in a speech written by Buchanan and given in Montgomery, Ala., again gaining national attention. “In Spiro Agnew,’’ recalls Buchanan, “I had found a fighting ally in the White House, a man with guts and humor, willing to give back as good as he got, who did not flinch from battle. He relished it.”

Until Agnew’s last battle, which he couldn’t win. Buchanan believes, based on his close observation of Agnew’s political talents, that the vice president likely would have become president of the United States had he left the practices of Annapolis back in Annapolis. Based on my own close observation of the man, I would agree. As a late-arriving member of Agnew’s staff (taking him up on a year-old offer), I traveled with him as his writer during the 1972 campaign, logging with him some 45,000 air miles as he spoke in 56 cities in 36 states. My sharpest memory of those days (next to the memory of drinking Jack Daniels and smoking Camels with Frank Sinatra in Palm Springs) is the size and enthusiasm of the crowds. These people constituted Richard Nixon’s New Majority, those silent Middle Americans who’d been given voice by Nixon/Agnew, then by Ronald Reagan, and most recently by Donald Trump, who made them roar.

Buchanan discusses those Agnew speeches in some detail, not only because he believes they were the best he had written in those years but also because they had lasting impact. They led, he believes, to the blossoming of op-ed pages in the establishment press, conscious attempts, for a time, to include conservative spokesmen in post-presidential-address instant analyses, and programs such as the The McLaughlin Group, Capital Gang, and Crossfire, with conservatives going toe-to-toe with liberals on an equal footing.

Buchanan waxes wistful about those days. “For me,’’ he writes, “these were the best of times. The President had stopped offering olive branches to the antiwar movement and came out fighting … calling on his countrymen to stand with him for peace with honor.” In those years, Pat Buchanan was the Happy Warrior—smarter, faster, and more intelligent than his antagonists, traveling with Agnew, reliving the previous campaigns with Nixon.

And then, with the historic landslide victory of 1972, the music stopped. Nixon henchmen Haldeman and John Ehrlichman implemented a full-scale staff restructuring, the most important element of which was building an iron wall around the president that effectively put him out of touch with the real world, making access difficult for his oldest friends and supporters. And at about the same time, the first drips from Watergate were becoming audible. From then on, the story begins the inevitable downward spiral. With the resignation of Agnew, after he pleaded nolo contendre to corruption charges, I was asked to join the Nixon writing staff. I shared offices with Aram Bakshian and Ben Stein, next to Pat Buchanan’s. During that last year of the Nixon presidency we came to count Buchanan as a friend and a man to be admired. Always direct, dead honest, a prodigious worker, highly intelligent, and fiercely loyal, he was Richard Nixon’s good right arm from the earliest days to the end.

During that period, when the latest leaked stories from the Washington Post and the New York Times were being lobbed daily like mortar shells into the White House, Buchanan was called to appear at the televised Watergate show trials. Straightforward, unapologetic, and with a knowledge of politics and political history that put his interrogators to shame, he won the respect and admiration of the venerable committee chairman, Sam Ervin—and, in the process, brought a brief measure of relief and even hope to an embattled White House.

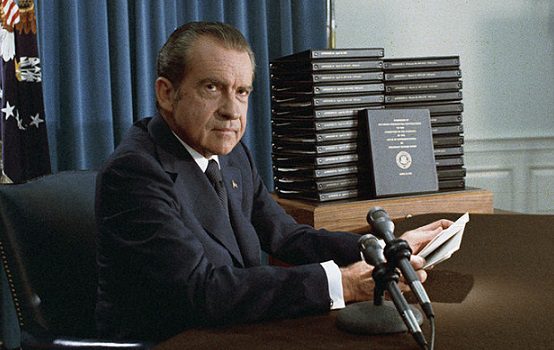

He also advised the president on how to tough it out. Destroy the tapes. Simple, direct, and easily done, before they became the center of the investigation. “Had Nixon followed my advice and burned the tapes,” he writes, “he would have saved his presidency and served out his term, and his reputation and place in history would not be what they are today.” In the end, it was just one tape, dated June 23, 1972—initially withheld, then released—that caused the Judiciary Committee to vote for impeachment. With the subsequent firestorm, his hopes of surviving a Senate trial were gone. He could remain in office and “force the Senate to convict and remove him. Or he could surrender his presidency.”

“Nixon,’’ writes Buchanan, “chose to put country and family first and end the agony.”

Until his death in 1994, Richard Nixon worked tirelessly to reestablish his reputation as an authority on world affairs. During his presidency he had frequently stated that his primary objective was to construct “a lasting structure of peace,” and he had made an impressive start on that—the trip to China (Buchanan disapproved on principle) and a new relationship with the Soviet Union that would ultimately shift the international balance of power in our favor. During the 1973 Yom Kippur war, he mounted a strong resupply airlift (Buchanan approved) that brought Nixon the accolade from Golda Meir that he was the best friend Israel ever had. And he achieved this without permanently damaging the U.S. relationship with Egypt (that folly was left to Barack Obama), where in one of his last foreign trips he was treated like a conquering hero, having “converted the largest Arab nation from a virtual Soviet satellite … into an ally.”

In June 1974, for what would be his last foreign trip, Buchanan traveled to Moscow to put together a briefing book for Nixon’s summit with Leonid Brezhnev. While at the Kremlin, he writes, “I got the White House Communications Agency to put through a call to my father’s accounting firm and told Pop, a Pius XII Catholic and admirer of Joe McCarthy, that his son was calling from inside the Kremlin.”

In June 1974, for what would be his last foreign trip, Buchanan traveled to Moscow to put together a briefing book for Nixon’s summit with Leonid Brezhnev. While at the Kremlin, he writes, “I got the White House Communications Agency to put through a call to my father’s accounting firm and told Pop, a Pius XII Catholic and admirer of Joe McCarthy, that his son was calling from inside the Kremlin.”

Pat Buchanan, now billed as America’s leading populist conservative (and, though he would deny it, an intellectual), a writer whose prose is blessed by that unique Irish writing gene, has given us a powerful and poignant personal narrative, rich in anecdote, of his role as confidant and strong right arm to one of the most brilliant and controversial presidents in American history.

As he points out, Nixon’s White House Wars will no doubt be the last memoir/history of the Nixon presidency by a senior adviser and friend who was there and played a major role throughout Nixon’s presidential years. As such, it is required reading for aspiring politicians, for students and teachers of American history, and for anyone who appreciates good writing and a story well told.

John R. Coyne Jr., a former White House speechwriter, is co-author with Linda Bridges of Strictly Right: William F. Buckley Jr. and the American Conservative Movement.