Industrial Poison: The Third Phase of an Overdose Boom

Seventy thousand Americans died from drug overdoses last year. That figure shattered 2016’s record, and made 2017 the deadliest year for drugs in the past two decades. Drugs killed more people than car crashes and guns, and resulted in more deaths than homicide and suicide.

From one perspective, this latest news simply extends the ongoing, monotypic “opioid epidemic”—48,000 of the 70,000 deaths involved opioids in some way, whether prescription pills or illicit powders.

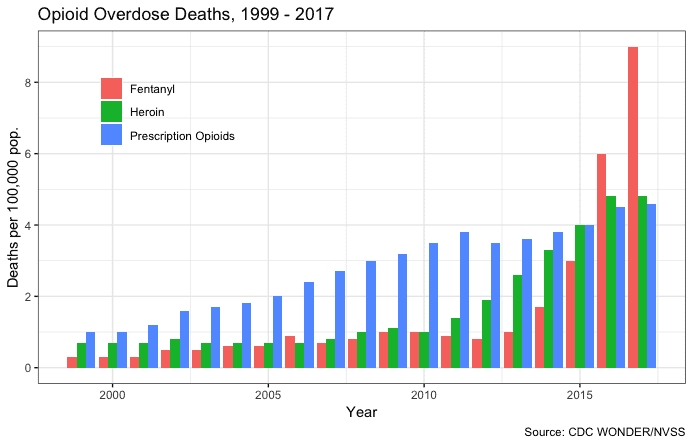

But from another perspective, the 2017 data suggest that we are entering the third phase of a multipart drug-death boom. First, prescription opioid deaths rose steadily over at least 15 years, as a result of uninhibited prescribing practices and negligent pharmaceutical firms. This eventually led to a government crackdown on prescriptions, which prompted users to switch to dirt-cheap Mexican black-tar heroin. As a direct result, heroin deaths almost quintupled between 2010 and 2016.

Then, in 2015, deaths from synthetic opioids—meaning predominantly fentanyl and its analogs—suddenly doubled. In 2016, they doubled again, hitting 20,000. If CDC’s estimates are correct, they probably killed 30,000 people in 2017, more than any other drug has at any point in the past twenty years.

Synthetics are deadlier than meth. They are deadlier than crack. And they may very well get deadlier.

Explaining synthetic opioid deaths as part of a single opioid epidemic—an indirect consequence of the original prescription wave decades ago—has a great deal of explanatory power. But it drastically deemphasizes the other half of the phrase “synthetic opioid.” The method by which fentanyl is produced matters as much as, maybe more than, which receptors it binds to.

The technological possibility of exclusively human-synthesized drugs, combined with their adoption from the pharmaceutical industry by drug traffickers, adds up to a wholesale restructuring of how drugs are made. This transformation has been decades in the making, but the overwhelming rate at which synthetic drugs are spreading—not just fentanyl, but a bevy of new, man-made substances—indicates that it has now come to a head.

The roots of this synthetic revolution go back a long way. Drugs can be (imperfectly) classified into one of three categories: natural, semisynthetic, and synthetic. The earliest drugs known to humans were natural; for example, the sticky depressant extracted from the latex of the poppy pod, or the heady stimulant of the coca leaf. Although these are habit-forming, even debilitating, they are generally deadly only to more vulnerable or chronic users.

Natural drugs are the product of plants which organically produce trace quantities of the intoxicating substance. The application of chemistry to concentrate, purify, or otherwise alter this product results in a semi-synthetic drug. Heroin, for example, was first refined for sale from the poppy in 1898. Cocaine is similarly semi-synthesized from the aforementioned coca plant.

The limiting factor in the supply of semisynthetic drugs is generally their natural precursor. Large fields of poppies and/or coca are resource-, labor-, and land-intensive, and make for prime targets for government drug suppression. Additionally, organic biosynthesis can be haphazard, yielding fewer psychoactive alkaloids than an ideal artificial synthesis could. And elaborate refinement processes usually do not preserve all of the plant’s initial product. In other words, semi-synthetic heroin and cocaine production is always limited in how efficient—and therefore profitable—it can be.

This natural limitation is a burden for pharmaceutical firms, which are forced to source legitimate organic precursors from just a handful of countries. As such, there has long been a desire to skip the organic precursors altogether, coming up with man-made substitutes, synthesized entirely from simple, readily sourced precursors.

Such syntheses are not that complicated, requiring no more knowledge than is to be expected of a competent pharmaceutical chemist. Thus, synthetic drugs were commonplace in the 20th century medical industry. Fentanyl, for example, was first synthesized by Janssen Pharmaceutica chemists as early as 1960, and has been in medical use ever since to treat cancer patients.

Synthetic drugs entered the illicit marketplace, too, at least wherever there was the knowledge to produce or divert them. Early illicit fentanyl analogs, known at the time as “China White,” killed at least 100 people in California in the 1980s. In the mid-1990s, the synthetic psychotropic phenylethylamine grew in popularity thanks in large part to the publication of a single book. But in terms of market impact, these early illicit synthetics tended to play second fiddle.

Then, in the early 2000s, the number and variety of synthetics in the black market took off. It’s not perfectly clear why, although global supply chains and fast international shipping may have been a driving factor. The rise of the internet was also a contributing factor not only because drugs could be sold online, but because it democratized access to an extensive synthetics literature. “By around 2006,” an editorial from the journal Drug Testing and Analysis explains, “it became clear that manufacturers of new substances were now trawling the world’s scientific and patent literature in search of failed pharmaceuticals or, as they also became known, ‘designer medicines.’”

Unsurprisingly, illicit chemistry produced deadly consequences. The first synthetic drug crisis was arguably the mid-2000s meth epidemic, when both large and small producers synthesized methamphetamine from pseudoephedrine pills, which themselves begin life with a simple yeast-driven synthesis. (Today, most of the meth in the United States is synthesized in bulk in “superlabs” in Mexico based on Chinese-sourced precursors.)

The meth epidemic came and (sort of) went, but that was only the beginning of synthetics’ market penetration. Designer drugs—officially called “new psychoactive substances” (NPS)—began to spread through the American and European marketplaces under claims of being a “legal high.” Synthetic cannabinoids, often called “K2” or “spice,” are marketed as a cheaper, more readily available marijuana. Synthetic cathinones—which mimic the natural stimulant component of the khat plant—are sold as an alternative to MDMA, meth, cocaine, and other stimulants, often under the label “bath salts.”

Unlike the 20th century synthetics, which were marginal compared to cocaine and heroin, these new synthetic drugs are shockingly popular. That’s in large part because, due to their synthetic nature, they are especially appealing to the 21st century drug dealer.

The most obvious reason is simple: synthetic drugs are cheap. The removal of organic factors from the drug production process, as discussed above, reduces the materials cost of the drug substantially, as well as the amount of space and manpower dedicated to its production. Fentanyl’s “cost effectiveness” was one reason why pharmaceutical firms were attracted to it in the first place. Estimates indicate that a kilogram of fentanyl costs about $4,000 to buy from China, compared to about $6,000 for an equivalent mass of heroin. The other NPS’s are similarly cheap.

The cost effectiveness is then combined with synthetics’ enhanced potency. Fentanyl is 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine (heroin is about twice as strong), with a standard dose measured in millionths of a gram. Synthetic cannabinoids produce far stronger highs than organic marijuana, which is why the former can poison people and the latter rarely does. Cathinones are known to result in “psychosis, hyperthermia and tachycardia… combative or violent behaviors… extreme agitation, delirium and hyperthermia in conjunction with rhabdomyolysis and ensuing kidney failure.”

Low costs plus potency equals profitability, which is why, for example, a kilogram of fentanyl—bought, again, for $4,000—can sell for $1.6 million on the street. That’s in part because synthetics are often used as an adulterant, reducing dealers’ costs and increasing the kick of heroin and fake pills. A small volume of fentanyl can be divided up among many doses, making its overall profitability higher than heroin’s.

On top of all of this, synthetic drugs have the advantage of a complicated legal status. Their synthetic nature means that governments attempting to criminalize them must either control often-commonly-available precursor chemicals or ban the substances themselves. But precursor bans risk running afoul of legitimate producers, and are also easily circumvented with an international shipping network. Bans based on chemical structure are even easier to get around, as illicit chemists can simply create another analog with a different structure that has the same effect.

For traffickers, then, synthetics are a dream come true. They are cheap, easy to produce, and of arbitrary potency. The laws surrounding them are murky at best, and the drugs themselves are immensely profitable.

All of this raises an obvious question: what, if anything, can be done to combat the rise of synthetics? As with any drug policy problem, there is no single, silver-bullet answer. A response will require a combination of approaches to even begin to tackle the problem.

First and foremost, drug enforcement and public health officials desperately need more data. The rapid increase in the number of synthetic drugs has left local, state, and federal agencies struggling to coordinate and keep track of the shifting threat on the ground. A recent report authored by a bevy of health and enforcement officials recommends re-establishing standardized postmortem toxicology testing guidelines, developing new technologies for assessing drug identity and potency, and developing better drug identification resources so that they have a clearer understanding of what’s going on.

On the supply side, one issue which must be addressed as soon as possible is the U.S. Postal Service’s role as an unwitting carrier for the overwhelming majority of fentanyl entering the United States. A Senate investigation tracked 300 Americans in 43 states who, over the course of only six months, bought $230,000 worth of fentanyl and other synthetic drugs online. Bipartisan legislation currently in Congress would render the USPS no longer exempt from having to collect advanced electronic data on many of its packages, making it easier to identify and interdict drug dealers.

Controlling the means by which synthetic drugs enter the country is less important than doing something about where they are coming from. As numerous indictments have shown, the overwhelming majority of synthetic drugs are produced by Chinese traffickers in factories located in East Asia. The Chinese government has scheduled 130 synthetic drugs and multiple precursor chemicals. But it has also dismissed the fentanyl epidemic as an American problem, which should be dealt with by reducing American demand.

This dismissive attitude ought to be unacceptable to American negotiators; the PRC’s laxity is directly responsible for American deaths. We should seek the extradition of indicted Chinese fentanyl traffickers, as well as a commitment to further scheduling and the shutting down of China-based drug labs.

Of course, a supply-side approach is not adequate to addressing mass addiction and death. Treatment with counseling and medication ought to be a central policy priority, simply as a matter of reducing deaths.

To combat synthetics specifically, however, what is really needed is education. CDC data suggest that fentanyl adulteration largely explains the continued increase in prescription opioid deaths since 2010. Even surging cocaine deaths may be explained by fentanyl adulteration. Present users need to be made aware of the threat of adulteration, while future users need to know that synthetic substitutes may be more dangerous than labels claim.

This is especially important for young would-be drug users. For example, making sure that teens know that K2 is far more dangerous than marijuana is important when the synthetic drug is the second-most popular substance—other than alcohol or tobacco—among 10th and 12th graders.

But even if the preceding proposals are implemented, it is important to keep in mind that we cannot predict what the future holds for America’s drug crisis. The fentanyl wave could break, just as the meth wave did. But it is also possible that we are only experiencing the first wave of an even bigger tsunami. If we are, synthetics will be the primary reason.

Charles Fain Lehman is a staff writer for the Washington Free Beacon. He writes about policy, covering crime, law, drugs, immigration, and social issues. Reach him on Twitter (@CharlesFLehman) or by email at lehman@freebeacon.com.

Comments