Acquitting Elvis of Cultural Appropriation

Bruce Springsteen, in his underrated song “Local Hero,” sings, “First they made me the king / Then they made me pope / Then they brought the rope…”

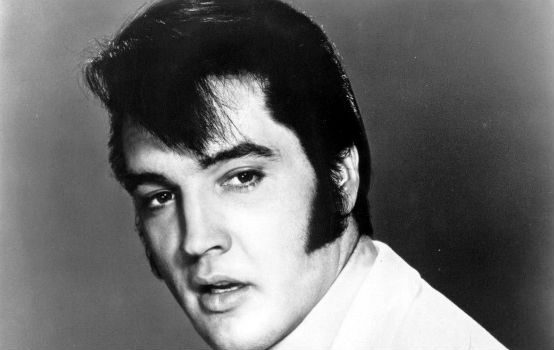

It was not long ago that Elvis Presley—one of the musicians who inspired Springsteen, John Lennon, and many other legends—had a permanent home in the American pantheon. For all his flaws, he was an original and an innovator who helped give rise to rock and roll, youth culture, and unscripted, artistic expression in popular entertainment.

It was because of his representation of the American ideals of freedom and individuality that in 1959 protesters against Soviet tyranny in East Berlin carried placards bearing his image, and chanted the name—not “George Washington” or “John Kennedy”—but “Elvis!”

Today, the protesters are storming the pantheon, looking to demolish any trace of Presley iconography.

Hostility towards Elvis is not merely the result of countless impostors transforming him into kitsch in the karaoke lounge; it’s also due to the tired and dull accusation that Elvis is a musical thief, the latest amplification of which relies on the academic buzzwords “cultural appropriation.”

Thus does Michael Eric Dyson charge Elvis with “performing a derivative blackness,” while Kiana Fitzgerald, a writer and DJ, claims that Elvis did nothing more than sing a “watered down version of black blues.”

The problem with the view of Elvis as racial pickpocket is that it is dependent upon a disciplined commitment to ignorance.

Sam Phillips, the founder of Sun Studio, believed that, through mixture of the correct artistic and commercial chemistry, he could encapsulate the magical formula for musical entertainment visible and palpable in the bars on Beale Street, the churches in the fields, and the worn-out wooden floors at barn dances. Having already recorded B.B. King, Howlin’ Wolf, and the very first rock and roll song—“Rocket 88” by Jackie Brenston—he was still in search of a star, someone charismatic, talented, and, yes, white, who could bust ribald rhythm and blues through the door of the mainstream.

Phillips did not think he’d found his man when a skinny 19-year-old truck driver walked into Sun and shyly announced himself as “Elvis Presley.” As a forecast for the carnal spell Elvis would cast on an entire world of women, it was Phillips’ secretary, Marion Keisker, who insisted to her boss that the young man, as nervous and unfocused as he appeared, had something mysterious and erotic about him.

Convinced to give him one audition, Phillips arranged for Bill Black on bass and Scotty Moore on guitar to record with Elvis, who would play rhythm guitar and take lead vocals. The night dragged on without producing anything but boredom and frustration. Phillips watched Elvis struggle to find a rhythm, stumbling and fumbling over his vocals. His patience exhausted, he instructed everyone to pack up and go home.

Perhaps in revolt against his own disappointment, Elvis summoned a demonic angel of musical possession. As Black and Moore put away their instruments, he grabbed his guitar and at breakneck speed started shouting an old, slow blues song: “That’s all right, momma / That’s all right with you/ That’s all right, momma / Just any way you do…”

Phillips darted into the music room as if he was escaping a burning building. “What was that?” he asked Elvis. Already feeling dejected from hours of failure, the young singer said, “Oh, I’m sorry. I was just messing around.”

“Well, whatever it was you need to do it again.” Two days later Phillips gave Presley’s first single, “That’s All Right”—an uptempo reinterpretation of the Arthur Crudup song—to a Memphis DJ. Reaction was so powerful that he played it 14 times before his shift ended.

The man who would become the world’s first rock star had no plot to “steal black music,” or even create a particular type of music. The success and story of his first single and his rocket launch into superstardom was the natural result of a primal, emotional, and carnal explosion of instantaneous creativity. “Music has been for some centuries,” the abstract painter Wassily Kandinsky wrote, “the art which has devoted itself not to the reproduction of natural phenomena, but rather to the expression of the artist’s soul.”

Elvis began singing before he could even remember. Bouncing on his mother’s knee in church, he would try to mimic what he heard from the soloists in the choir. When he was eight or nine, he began taking solos of his own. The radio in his house in Tupelo, Mississippi, was always tuned to country. At the age of 10, Elvis took fifth place in a talent show at a county fair with his rendition of “Old Shep.”

The Presley family moved to Memphis during Elvis’s teenage years. When their Sunday morning service ended, Elvis would ride his bicycle to sit in a back pew of a black church, loving what he heard as much as he did old country ballads. He not only bought clothes on Beale Street, but snuck into the bars to listen to rhythm and blues music. Intrigued by the white kid holding up the wall, a few bandleaders would invite him on stage to sing harmony. As an adolescent, he also attended gospel quartet festivals, where he snuck backstage to meet one of his heroes, J.D. Sumner, the same baritone who would one day provide backup vocals in Elvis’s band throughout the 1970s and sing at the funeral service for Elvis’s mother.

“My music is a combination of country music, gospel, and rhythm and blues,” Elvis explained in 1971. He attuned the sounds of white gospel quartets, black gospel spirituals, rural country, and urban blues to the same frequency as his spirit, providing a tour of the musical milestones and memories of his young life. It wasn’t black. It wasn’t white. It wasn’t blues. It wasn’t country. It was the transcendence of classification made possible only in the multicultural, multiethnic American experience. To reduce Elvis’s spontaneous invention to “derivative blackness” is to simplify the complex and demonstrate narrow and shallow thinking in violation of human ambition.

It is easy to make the case in strictly musical terms. Larry Nager, a historian and guitarist, writes in his book Memphis Beat: The Lives and Times of America’s Musical Crossroads, “Elvis’s guitar style (on That’s All Right) was strictly country rhythm, open chords with ringing strings strummed with a straight pick. Those who say Elvis did nothing more than rip off black bluesmen need look no further than his guitar playing for proof of the contrary. No bluesman ever played rhythm like that.”

Elvis sang with the full-throated, ecstatic delivery of gospel and blues, but he never eliminated his country twang. For his follow up to “That’s All Right,” he rearranged “Blue Moon of Kentucky”—a song by the “Father of Bluegrass,” Bill Monroe—into a rockabilly hit. It is for good reason that Elvis is a member of the Country Music Hall of Fame.

Elvis exercised the oft-neglected magic of the American experience. It is the magic that Walt Whitman celebrated when he declared the United States “a new nation in need of new poets.” Elvis became one of those poets, someone who could not only express but also embody the American novelty that is its emphasis on individual freedom and its racial, religious, ethnic, sexual, and regional diversity. It makes sense in an era of mediocrity in American culture, with our understandings of everything from politics to pop music reduced to slogans on social media, that old and boring criticisms of Elvis have found new ears.

A documentary, Elvis Presley: The Searcher, recently premiered on HBO. It is visually captivating but conceptually dull, as it presents an overly sanitized version of the Elvis story. The singer’s obvious problems—his capacity for self-destruction and his inexplicable passivity while stupid and greedy management cornered him into making bad movies and music—demand analysis, and make Elvis unfit, like anyone else, for hagiography.

The documentary does succeed, however, by emphasizing the truth Tom Petty gives concerning Elvis’s achievement: “We shouldn’t make the mistake of writing off a great artist by all the clatter that came later. We should dwell on what he did that was so beautiful and everlasting, which was that great, great music.”

Elvis’s artistry was the administration of fusion. As Petty reminds viewers, what he created wasn’t rock and roll, but “something new,” music that was a touchstone for all the varieties of the American experience. And he created himself: for better and for worse the first televisual-musical icon.

Bob Dylan said the first time he heard Elvis, he felt like he was “busting out of jail.” Elvis’s early success came to symbolize emancipation, and the brilliance of crossing borders in creative pursuit.

The “cultural appropriation” cry is an attempt to reinforce the boundaries of parochial banality. More than any American performer, Elvis was a product and promoter of multiculturalism. It is a sad irony that the Left has now cast him as a villain. Even an incomplete list of those who disagreed is sufficient to expose the absurdity of the charge: John Lee Hooker, James Brown, Rufus Thomas, Chuck Berry, and B.B. King—who once said that “Elvis was everything.”

To deny the authentic exploration of Elvis is to vandalize the American promise and human idea of self-invention. Rather than encouraging a freethinker to bust out of intellectual and cultural jail, it places the spirit in a solitary cell.

David Masciotra (www.davidmasciotra.com) is the author of four books, including Mellencamp: American Troubadour (University Press of Kentucky) and Barack Obama: Invisible Man (Eyewear Publishing).

Comments